Менопауза: Управляющий настроение, память и женские сексуальные дисфункции

WHEC практики Бюллетень и клинических управления Руководство для медицинских работников. Образования гранта, предоставленного здоровья женщин-образовательный центр (WHEC).

Many women complain of changes in their cognitive function during the menopausal transition. Reproductive aging in women is a normal progression through three stages: reproduction, the menopausal transition and finally postmenopause. Most women move through the stages in this pattern, albeit at a variable rate. The menopausal transition can be divided into two stages: 1) early, which begins on average around age 42, and 2) late, which begins on average around age 46 and ends, on average, at age 51, with final menstrual period (1). The menopausal transition is associated with diminished fertility, menstrual cycle irregularity, and vasomotor symptoms. The period that includes the menopausal transition and the first year of amenorrhea is commonly referred to as the perimenopause. The median age at menopause is 51; approximately 1% of women will reach menopause by age 40, 10% by age 46, and 90% by age 55 (2). In addition to population estimates, a woman’s mother’s age at menopause may provide some guidance as to when the woman will experience her final menstrual period. Multiple studies have shown an association between a mother’s and a daughter’s age at menopause. Earlier the mother experiences menopause, the poorer the ovarian reserve in the daughter between ages 35 and 49 (3). The commonality may be due to genetics or shared behaviors, such as tobacco use, dietary intake, and physical activities.

The purpose of this document is to discuss current management of mood, memory and female sexual dysfunction problems associated in this age group. The review describes the diagnostic criteria, helpful screening tools, and initial treatment guidelines in order to better equip the obstetricians and gynecologists to manage these patients. Patients and their clinicians can be reassured that for the majority of women, cognitive function is not likely to worsen in postmenopause in any pattern other than that expected with normal aging. Although it is not likely that in postmenopause, a woman’s cognitive function will return to what it was premenopause, she may adapt to and compensate for the symptoms with time. Stimulant medication may have a role in the treatment of subjective cognitive impairment, particularly for women with comorbid fatigue or impaired concentration who are not showing evidence of objective impairment. There is some evidence that modifying lifestyle factors can decrease the risk of dementia and even cognitive decline associated with normal aging. Patients should be encouraged to maintain a normal body weight, exercise regularly, maintain a nutritious diet, engage in regular social activities, and participate in cognitive exercise (reading, crossword puzzles, etc.). They should also be encouraged to maintain good cardiovascular health, with treatment of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. Primary care providers, including obstetricians and gynecologists, are in a unique position to identify and treat these patients because women may feel more comfortable discussing their symptoms and initiating treatment with providers whom they have seen regularly for many years.

MANAGING MOOD | DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS

Diagnosis and treatment of depression in a primary setting are subject to practical limitations, including lack of time and resources and the potential overlap of medical comorbidities. Many women do not seek or cannot access psychiatric services for management of their depressive symptoms and therefore many remain undiagnosed and/or inadequately treated.

BACKGROUND

More than 20% of the US population will suffer from an episode of depression, and women have 2-fold greater risk than men (4). Several large prospective trials have shown an increased risk of depressed mood and a major depressive episode during the menopausal transition. Risk factors associated with development of depressed mood during the menopausal transition include history of depression, insomnia, stressful life events, inadequate social support, elevated body mass index, current smoker status, younger age, and African-American race. In addition, hormonal changes taking place during menopause play a role, as evidenced by increased risk of depression in association with variability of estradiol levels, and surgical menopause. Depressive symptoms tend to precede hot flashes in women who develop both symptoms (5).

Definitions

A major depressive episode is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (2013) as 5 or more of the following symptoms, present most of the day nearly every day for a minimum of two consecutive weeks. At least one symptom is either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure.

- Depressed mood;

- Loss of interest or pleasure in most or all activities;

- Insomnia or hypersomnia;

- Significant weight loss or weight gain or decrease or increase in appetite;

- Psychomotor retardation or agitation;

- Fatigue or low energy;

- Decreased ability to concentrate, think, or make decisions;

- Thoughts of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt;

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation, or a suicide attempt.

DIAGNOSIS

Many women do not seek or cannot access psychiatric services for management of their depressive symptoms and therefore many remain undiagnosed and/or inadequately treated. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in a primary care setting are subject to practical limitations, including lack of time and resources and the potential overlap of medical comorbidities. A complete interview for depressive symptoms in every perimenopausal patient is neither necessary nor efficient. Screening tools can be used to determine who will need further evaluation. One appropriate tool, used frequently in the primary care setting in older adults, is the 5-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (10). This may be helpful in perimenopausal patients because it excludes physical symptoms related to medical illness and aging that may be present during menopause. The longer version of the GDS has been validated in both younger and older adults.

Geriatric Depression Scale

- Are you basically satisfied with your life?

- Do you often get bored?

- Do you often feel helpless?

- Do you prefer to stay at home rather than going out and doing new things?

- Do you feel pretty worthless the way you are now?

A single point is given for a “no” response to the first item and a “yes” response to each of the other four items. A score of 2 or more points is considered a positive screen for depressive symptoms.

Referral of patients to a mental health specialist depends on the primary care provider’s level of expertise in assessment and treatment of depression, the availability of mental health resources, and patient/family preference. Evidence of suicidal or homicidal ideation, inability to care for self or others, failure to respond to initial treatment trials, presence of psychotic symptoms, history of bipolar disorders or psychotic disorder, significant psychiatric comorbidity, or an unclear diagnosis of depression usually require immediate referral to a mental health specialist. When a perimenopausal or postmenopausal woman presents with cognitive complaints, the practitioner will most often be able to reassure her that these complaints are frequent and not necessarily progressive, and may even improve over time. As is true for depressive symptoms, patients with cognitive impairment will often first present to a primary care provider such as an obstetrician and gynecologist. Women who report worsening of verbal memory are likely experiencing a normal change associated with the menopausal transition and can be reassured.

MANAGEMENT

First-line treatment of a major depressive episode may involve psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of these modalities. Treatment is often tailored to patient preference and severity of depression. More severe episodes usually require combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. A mild to moderate episode may respond to either psychotherapy or an antidepressant alone. If a patient is interested in a trail of medication, she may benefit significantly if it is started soon after diagnosis. Gynecologists frequently make the initial diagnosis of depression and are in a position to begin this treatment in a timely manner when possible.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are first-line medications used in treatment of depression. Once initiated, it may take 6 to 8 weeks for a patient to respond. Often, however, patients notice a difference within the first month of treatment. Dosage can be titrated to achieve improved effectiveness, with increases approximately every month as tolerated. Of particular concern in this population is the risk of sexual side effects (decreased libido and difficulty with arousal and achieving orgasm). Depression can also affect a woman’s sexual function, but the risks of discontinuance of medication may outweigh the burden of these adverse effects. A switch to a different SSRI, other antidepressant class, or addition of bupropion, which acts on the dopaminergic system, may be helpful. Estrogen can be helpful in treating perimenopausal depression and changes in sexual function as well. Conversely, several different SSRI and selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SSNRI) antidepressants have been shown to be effective in treating perimenopausal vasomotor symptoms. For mild to moderate depressive episodes, limited evidence suggests that estrogen may be beneficial, but only for women who are perimenopausal. Dose equivalents to 50 to 100 mcg of transdermal 17-β-estradiol daily (equivalent to a 0.625- to 1.25-mg oral dose of conjugated equine estrogen daily) have been shown to be modest benefit (12). Although the North American Menopause Society does not recommend estrogen use for sole treatment of depression or cognitive dysfunction, it may be helpful in patients who also experience vasomotor symptoms.

SSRIs and SSNRIs used to treat vasomotor symptoms:

Drugs | Dose | FDA Approved | Indication |

Paroxetine | 7.5 mg/day | Yes | Moderate to severe hot flashes, night sweats |

Paroxetine CR | 12.5-25 mg/day | No | Moderate to severe hot flashes |

Fluoxetine | 20 mg/day | No | Moderate to severe hot flashes |

Venlafaxine | 37.5-75 mg/day | No | Moderate to severe hot flashes |

Desvenlafaxine | 100 mg/day | No | Moderate to severe hot flashes |

Several other classes of antidepressants are also available for patients whose depression has failed to respond to an SSRI or who have difficulty with adverse effects, although a trial of a different SSRI first may prove beneficial. SSNRIs such as venlafaxine or duloxetine can be particularly helpful in patients with comorbid anxiety. Bupropion can be helpful when patients have low energy, but can exacerbate anxiety and insomnia (13).

Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors are useful in treatment-resistant depression. They often are associated with more significant adverse effects (particularly in older patients), may interact with many medications, and can pose a serious overdose risk. Electroconvulsive therapy is often very well tolerated, safe, and effective in older patients whose condition fails to respond to medications or who do not tolerate medications.

Several forms to psychotherapy may be beneficial for patients with depression, including cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and psychodynamic psychotherapy. A range of providers with psychotherapy training are available, but resources may be limited by a patient’s insurance, location, and financial situation. Women who present with multiple psychological complaints such as depression plus anxiety or bipolar disease are usually better referred to a mental health specialist.

Distinguishing Depression, Dementia and Delirium: Clinical Presentation

- Depression: Variable onset, often abrupt, reversible with treatment; weeks to several years’ duration; sensorium clear; attention span normal but easily distracted; selective memory impairment; intact thinking but expresses hopelessness, helplessness and often coincides with major life changes.

- Dementia: Gradual onset, irreversible, chronic, progressive, long duration; shortened attention span; impaired memory; difficulty with abstraction, problems with word finding, confabulates; and struggles to remain independent.

- Delirium: Acute or subacute onset, reversible or alleviated with prompt appropriate treatment; short duration (hours to one month); sensorium clouded; impaired, fluctuating attention span; impaired recent and immediate memory; thinking is disorganized, distorted, speech incoherent and associated with trauma, disease, infection, and/or chemical intoxication.

MANAGING MEMORY DISORDERS

A gradual decline in some cognitive functions occurs with normal aging, beginning around age 50. Many women complain of changes in their cognitive function during the menopausal transition, with the majority reporting worsening of verbal memory. In one study of 205 menopausal women, 72% reported some subjective memory impairment (6). The symptoms were more likely to be associated with perceived stress or depressive symptoms than perimenopause, but overall, cognitive symptoms were more prevalent early in the menopausal transition. Women exposed to any form of hormonal therapy prior to their final menstrual period performed better on memory testing than those who initiated it after menopause (7). Whether women who have cognitive difficulties during the menopausal transition are at increased risk of cognitive impairment later in life is unknown.

As individuals age, they may notice changes in memory and may express concern that they are developing Alzheimer’s disease. Age-associated memory impairment, a common and normal process relating to structural and functional brain changes, should not be confused with the memory loss associated with a dementia. Age-associated memory impairment, also called benign senescent forgetfulness, may accompany aging, but unlike Alzheimer’s disease, it does not include other cognitive impairments. Other factors, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, head trauma, alcohol or substance abuse, and side effects of certain medications, can also cause an apparent decline of short-term memory.

It is important to remember that some types of cognitive changes, together called mild cognitive impairment (MCI), are thought to be a sign of very early dementia. MCI and dementia are highly unlikely in people younger than 50, but the risk increases significantly with age, with greater than 10% of the population over age 65 at risk of developing dementia (8). Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia, but other types can occur with varying presentations, including vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia. In some individuals with MCI, dementia may never develop, and improvement can be seen over time. Depression can also be present with MCI, and it can be difficult to discern whether the depression is causing the memory impairment, or if MCI puts and individual at risk of developing depression. There is some evidence to suggest that depression may be an early manifestation of cognitive decline (9).

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)

In 2001, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) published practice guidelines for the early detection of progressive memory problems (8). The AAN workgroup of specialists identified the following criteria for an MCI diagnosis:

- Memory complaint, preferably confirmed by an informant;

- Objective memory impairment on standard neuropsychological batteries assessing memory (for age and education);

- Normal general thinking and reasoning skills;

- Ability to perform normal daily activities.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a spectrum of mild but persistent memory loss that lies between normal age-related memory loss and diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. The memory deficits are beyond those expected for the person’s age, and the individual persistently forgets meaningful information that he or she wants to remember. However, other cognitive functions may be normal, there is little loss of ability to work or function in typical daily activities, and there are no other clinical signs of dementia. Multi-step tasks such as shopping, making dinner, and paying bills may take longer than usual and more errors may be made, but overall, little or no assistance is required.

MCI patients do not meet criteria for dementia, which involves impaired daily functioning. The evaluation for MCI and dementia includes a thorough history provided by the patient and preferably a partner or family members in close contact with the patient. Medical history and review of systems will aid in determining if any other medical illnesses could be contributing (particularly infectious illnesses or disorders of the cardiovascular, neurologic, or endocrine systems). A medication history is also particularly important because often analgesics, anticholinergics, psychotropic medications, and sedative-hypnotics can affect cognition. Eliciting information about family members with dementia of possible early onset (before age 60) and other neurologic disorders is also important. A physical examination, including a basic neurologic exam and some cognitive assessment, should also be completed.

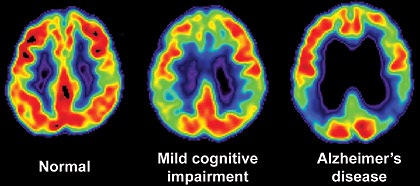

Many individuals with MCI have a high probability of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Those who are likely to progress to Alzheimer’s disease will have difficulty learning and retaining new information (36). Testing for biomarkers while making a diagnosis can identify people at risk for or who are progressing to Alzheimer’s disease but is only recommended for use in research settings. Biomarker testing standards and cut-points are not yet defined; however, low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) beta-amyloid levels combined with high CSF tau is considered a positive for MCI due to Alzheimer’s disease (36). Positron emission tomography (PET) amyloid imaging has also proven valuable for predicting progression to Alzheimer’s disease in research.

The cognitive test most often used as a screen for cognitive impairment is Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), which takes only a few minutes to complete (11):

Mini-Mental State Exam:

| Task | Maximum Score (points) |

| Orientation What is the (year) (season) (date) (day) (month)? Where are we: (state) (country) (town) (hospital) (floor)? |

5 5 |

| Registration Name 3 objects: 1 second to say each. Then ask the patient all 3 after you have said them. Give 1 point for each correct answer. Then repeat them until she learns all 3. Count trials and record. |

3 |

| Attention and Calculation Serial 7’s. Stop after 5 answers. Alternatively spell “word” backwards. |

5 |

| Recall Ask for the 3 objects repeated above. Give 1 point for each correct. |

3 |

| Language Name a pencil and wristwatch. Repeat the following “No ifs, ands, or buts”. Follow a 3-stage command: “Take a paper in your right hand, fold it in half, and put it on the floor”. Read and obey the following: “Close your eyes” “Write a sentence” “Copy this design” |

2 1 3 1 1 1 |

*The Maximum score is 30. A score lower than 24 is suggestive of dementia or delirium.

This tests a broad range of cognitive functions including orientation, recall, attention, calculation, language manipulation, and constructional praxis. A score of 24 points or less is suggestive of dementia or delirium. MMSE scores may also be influenced by age and education, as well as language, motor, and visual impairments. Disease Features Major Clinical Course Alzheimer’s disease Involvement of higher brain structures, neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid plaques. Accounts for 60% to 80% of all dementias. Memory and other cognitive deficits; Visuospatial impairment; Wandering; Aphasia

Onset: 60 to 80 years of age. May progress over 3 to 20 years

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). Cognitive deficits greater than expected for patient’s age. Cognitive decline;

No interference with activities of daily living. May or may not progress into dementia. Multi-infarct or vascular dementia. Multiple cerebral infarctions;

May be related to cardiovascular disease and/or diabetes. Dependent on location of infarct cognitive impairment;

Emotional lability; Dysarthria, dysphasia. Onset: 60 to 75 of age

Outcome depends on occurrence of infarcts. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Accumulated bits of synuclein protein; Rarely familial. Cognitive impairment; Symptoms fluctuate; Progressive over approximately 8 years. Parkinson’s disease Deficiency of dopamine. Movement disorders;

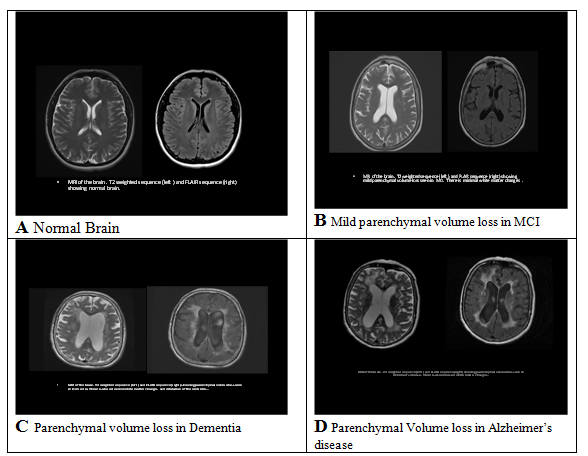

Dysarthria, dysphasia, bradykinesia; Late cognitive dysfunction. Onset >50 years of age;

Progression varies. Frontotemporal dementia (Pick’s disease, primary progressive aphasia, semantic dementia. Abnormal accumulation of protein in certain neurons; Rare; Predominately genetic. Cognitive impairment; Depression, Apathy, Wandering; Disorientation; Lack of inhibition. Onset: 35 to 75 years of age; May progress over 2 to 10 years. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Prion protein abnormalities; Spongiform changes in brain; Rare. Cognitive impairment; Myoclonus; Extrapyramidal movements. Onset: <60 years of age; Rapidly progressive. Normal pressure hydrocephalus Increase CSF in cerebral ventricles; Possible causes are subarachnoid hemorrhage, infection, trauma, tumor or post-surgical complications; Rare. Cognitive impairment; Difficulty with gait; Incontinence. Progression depends on cause. Huntington’s disease Autosomal dominant disorder. Cognitive impairment; Choreiform movements; Dysarthria, dysphasia, bruxism. Early-onset: <20 years of age; Late-onset: Middle age. Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome Severe thiamine deficiency; Associated with alcoholism, AIDS, cancer, and hyperthyroidism. Confusion; Permanent memory gaps; Motor and coordination difficulty. Progression may be halted with treatment; but existing damage is irreversible. Gerstmann Strӓussler Scheinker disease Prions suggested; Spongiform changes in brain; Extremely rare; Usually familial. Cerebellar ataxia; Cognitive impairment. Onset: 35 to 55 years of age; May progress over 2 to 10 years. HIV-associated dementia or AIDS dementia complex HIV infection. Cognitive impairment; Motor dysfunction paraparesis; Depression. Progression varies. Neurosyphilis Spirochete; Sexually transmitted disease; Rare; Occurs with delayed treatment. Cognitive impairment; Tremors, ataxia, Dysarthria. General paresis may occur 20 to 30 years after primary infection. Traumatic brain injury Consequence of head trauma. Memory impairment; Behavioral symptoms with or without motor and/or sensory deficits. Non-progressive; Repeated injuries can lead to progressive dementia. REM sleep: rapid eye movement sleep; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid: HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Initial laboratory work-up should include thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and vitamin B12 to rule out potentially reversible causes of cognitive impairment (hypothyroidism and vitamin B12 deficiency). Screening for neurosyphilis may be indicated, but only if there is a high clinical suspicion. Other laboratory studies, such as complete blood count, electrolytes, renal function and liver function tests, are neither recommended nor indicated unless specific clinical suspicion is present. Brain imaging should be completed if MCI or dementia is diagnosed. Once such a diagnosis is made, those patients should be referred to a neurologist or geriatric psychiatrist for further evaluation and/or treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is able to measure with considerable accuracy the size of intracerebral structures, such as the hippocampus, that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. It has been found that patients with Alzheimer’s disease have a decreased volume of the hippocampus when compared to non-affected individuals, and patients with some degree of atrophy are more liable to develop Alzheimer’s disease. MRI is also able to image cerebral atrophy and other abnormalities that are associated with decreased cognition or dementia. Non-contrast computerized tomography (CT) can also help in the diagnosis by identifying structural changes, such as infarcts or mass lesions that may be the cause of cognitive changes. Alzheimer’s disease was first identified and named in 1906 by Dr. Alois Alzheimer, a German neuropathologist. He had been treating a middle-aged woman who exhibited symptoms of memory loss and disorientation. Five years later, the patient died after suffering hallucinations and symptoms of dementia. The manifestations and course of the disease were so unusual that Dr. Alzheimer was unable to classify the disease into any existing category. Postmortem examination of the brain revealed microscopic and macroscopic lesions and distortions, including neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Healthcare professionals now know that while there is a strong and as yet incompletely understood relationship between aging and Alzheimer’s disease, they are not the same condition. The disease is recognized as a family, social, and economic problem. Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by insidious, severe, and progressive cognitive impairment that is irreversible and eventually fatal. Alzheimer’s disease accounts for roughly 60% to 80% of all dementias in the United States. It proceeds relentlessly, gradually destroying all cognitive functions. While the number of adults with Alzheimer’s disease doubles for every 5 years of age after 65 years, the disease is also seen (less frequently) in younger people. There are two types of Alzheimer’s disease: familial and sporadic. Familial Alzheimer’s disease follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, while sporadic Alzheimer’s disease has no known inheritance factor. Familial Alzheimer’s disease can be further classified as early-onset, when it occurs in individuals younger than 60 years of age, or late-onset, when it affects individuals older than 60 years of age. Early-onset type occurs in only 4% to 5% of cases, generally affects people 30 to 60 years of age, and is considered hereditary. There are roughly 200,000 people in the United States with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (37). Anatomy and Physiology Associated with Dementia With the help of motor and sensory nerves, the brain integrates, regulates, initiates, and controls the functions of the whole body. These processes rely on successful chemical and electrical interactions. Thinking, remembering, and learning do not occur in one single place within the brain. These processes are shared by many structures, especially the cerebral cortex, which directs the most intricate and complicated functions of the brain. Until recently, it was believed that the human body formed its full complement of neurons before and for a short time after birth; it could not create new ones after this period. However, researchers, including those at the Institute of Neurology in Sweden and at the Salk Institute, have found that the human brain retains the ability to generate new neurons throughout life. These findings may have an enormous impact on future approaches to the prevention and treatment of neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease. There are several chemical neurotransmitters active in the brain, including dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA), and acetylcholine; each has a fairly specific group of actions. Associated neurologic syndromes may be related to a deficit or overabundance of a particular neurotransmitter. An example is dopamine’s effects on movement, learning, and emotion and abnormalities in its concentration or action leading to pathological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease. The neurotransmitter that features most prominently in Alzheimer’s disease is acetylcholine. Dysfunction and reduction of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors is linked to adverse cognitive and neurodegenerative effects. The drugs that increase the cerebral levels of acetylcholine, such as the cholinesterase inhibitors, have been shown to provide some improvement in the cognition and function of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease Symptoms seen in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease are partially the result of damage to the hippocampus and the cerebral cortex, reflected in memory loss, impaired cognition, and atypical behaviors. The damage seen in Alzheimer’s disease is caused by changes in three major processes. The first process is based on the communication between neurons. Successful communication depends on reliable neuronal functions and the production of neurotransmitters. Any disruption of this process interferes with the normal function of cell-to-cell communication. The second process is cellular metabolism. Sufficient blood circulation is required to supply the cells with oxygen and nutrients such as glucose. The third process is the repair of injured neurons. Neurons have the capacity to live more than 100 years, and as such, they must continuously maintain and adapt themselves in order to survive. If this process slows or stops for any reason, the cell cannot function properly. The presence of neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques are the structural hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. Beta-amyloid and tau are two proteins involved in the formation of these abnormal structures. A form of tau, A68, is the major component of these tangles. In healthy neurons, the internal structures (called microtubules) are formed like long parallel tracks with crosspieces that carry nutrients from the body of the cells to the ends of the axons. In Alzheimer’s disease, the structure has disintegrated. The crosspieces formed from tau are twisted like two threads wound around each other. Amyloid plaques, made up of beta-amyloid mixed with dendritic debris from surrounding cells, are found in areas of the brain associated with memory. Knowledge of how beta-amyloid causes neuron death and forms plaques is incomplete, but it is known that the normally soluble amyloid becomes insoluble when the apolipoprotein E4 susceptibility gene (ApoE4) protein latches onto the beta-amyloid. The Role of Memory Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by cognitive impairment. Cognition includes all of the mental processes that are acquired over a lifetime. These processes provide humans with the ability to learn, think, make judgments, use logic and reason, and have insight. Memory is a major antecedent for developing mastery in these intellectual functions. Memory deficits are an early and progressive sign of Alzheimer’s disease. In order to understand the behaviors of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, it is necessary to understand the significance of memory, the process of remembering and recall, and the various types of memory. Memory is dynamic, developing in stages and constantly changing. Memory and learning are not separate functions. Both depend on the storage of data that can be retrieved at a later date. The ability to remember simplifies life, allowing minimum energy to be expended on routine activities. For example, arising in the morning and completing the activities of daily living requires little conscious thought. The tasks are performed by routine way of doing things. However, the person with memory deficits may be unable to recognize the bedroom, unable to find the bathroom, and unaware that teeth must be brushed or where the items are that is used to complete these tasks. Remembering and Recall The acquisition of a memory depends on several mechanisms. Information is received from the environment, and the senses perceive it, interpret it, and respond to it. There are three stages involved in this process. Information is acquired during the first stage; the information is taken in through the senses, perceived, and understood. If the information is visual, it enters the brain through electrical impulses coming from the retina, traveling through the optic nerve and into the cerebral cortex. A limited amount of this information is retained in short-term memory. Like a clipboard on a computer, the contents of short-term memory are constantly being lost and replaced with other information unless the contents are restored through repetition. For example, when a telephone number is looked up, it is usually remembered long enough to complete the call. This information will soon be forgotten if it is not used again for several days or weeks. However, if the number is dialed every day or several times per week for several weeks, it becomes firmly entrenched in the brain as long-term memory for the duration of use. There is a limited storage capacity for short-term memory. The second stage of memory is retention. Important information is placed in long-term memory, where the storage involves associations with words, images, or other experiences. This information can be recalled days, weeks, or years later. For a memory to be retained, it must be transferred from short-term to long-term memory. Physical changes take place in the brain to facilitate this transfer. Retrieval of information occurs in the third stage. Information is stored at an unconscious level and is later recalled, bringing it into the conscious mind. The accuracy and availability of the memory depends on how well the information was processed in stage two (retention). Some memories are easily recalled, others seem temporarily unavailable, and some seem to disappear from the mind completely. Types of Memory There are many types of memory. How the information is used depends on how the memory was formulated. Episodic memory pertains to remembering specific events associated with a particular time and place. Episodic memory requires no effort at learning. Remembering the details of a child’s birth, one’s wedding, or perhaps a catastrophic event are other examples of episodic memory. Semantic memory requires the conscious involvement of the learner. The knowledge is not associated with a particular time or place but is learned at some point in time. Skills such as using a telephone book, balancing a bank statement, cooking from a recipe, and reading a road map are examples of semantic type memories. Implicit memory is information learned without the conscious involvement of the individual. It is established through early and frequent repetition. Reciting the Pledge of Allegiance and singing “Happy Birthday” are the result of implicit memory. Social customs and manners, such as saying "please" and "thank you", develop through implicit memory. Motor memory is required for tasks utilizing motor skills, such as riding a bicycle, jumping rope, and dancing. Once learned, these skills are rarely lost even if not used for some time. Affective memory refers to feelings and emotions. Listening to a song may evoke memories of a person, place, or event. The aroma of a certain perfume may bring to mind a specific person. Cooking odors may elicit the memory of family holiday meals. Meeting a person for the first time may bring forth feelings of dislike until one realizes that the person resembles someone from the past. Semantic memory is the first type affected in the person with Alzheimer’s disease. The individual may notice that tasks that were once simple to perform are causing increasing frustration. Motor memory is eventually lost as activities requiring fine and gross motor skills become more and more difficult to access. Implicit memory often remains intact as long as the individual can communicate. Anyone who has worked with those with advanced Alzheimer’s disease has experienced the surprise of hearing a person in the later stages singing a favorite hymn during church service or an old song during a sing-a-long. There is some evidence that affective memory remains intact far into the disease. The decline in memory is usually most pronounced within 12 months after the final menstrual period. No specific monitoring is recommended, unless a woman experiences progressive memory loss. After evaluation cognitive complaints in a perimenopausal or postmenopausal woman, some treatment options may be useful. For the most part, though the absence of an established treatment for MCI limits the value of early detection. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors have been shown to provide benefit for patients with early dementia, but have not been shown to decrease the rate of progression to dementia in patients with MCI (14). Antidepressant medications may result in improved cognition if comorbid depression is present. Atomoxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor often used to treat adult attention deficit disorder, has recently been shown to provide significant subjective improvement in memory and attention in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women presenting with midlife-onset subjective cognitive impairment (15). Components of Care The care of people with Alzheimer’s disease is based on supportive and comfort measures, restorative care, prevention of complications, and management of coexisting illnesses. Admission to a long-term care facility at some point is inevitable for most people with Alzheimer’s disease. Few families have the emotional resources and energy to cope with care given 24 hours per day, 7 days per week. Like advanced directives, the topic of nursing home or long-term care facility placement should be discussed at the time of initial diagnosis. Making the decision for placement at a time of cri¬sis places undue stress on everyone involved. The availability of special care units (SCUs) increases the options for families who must make decisions regarding a loved one. Pharmacologic Treatment Guidelines Some pharmacologic agents have shown modest benefits in alleviating problems with cognition and behavior in research settings, though these benefits are often not realized in clinical use. These agents include several cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and memantine, a N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist. The most common adverse effects of ChEIs are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; with the most serious being cardiac arrhythmia and other cardio¬vascular and neurological effects. Memantine produces fewer adverse effects, and the dropout rate is similar to placebo. Other medications, such as antipsychotic agents and antidepressants, are occasionally necessary, but these agents can cause many unacceptable side effects (38). Although Alzheimer’s drugs can provide cogni¬tive improvement in a small cohort, the reality is that there are currently no medications promising substantial clinical benefit to the vast number of patients. As such, non-pharmacologic interven¬tions, including social, environmental, and behav¬ioral measures, are considered the most crucial treatment for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine are ChEIs that have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Tacrine was the first ChEI to be approved; however, the drug is no longer avail¬able due to its more severe side effects, including possible hepatic dysfunction. Rivastigmine and galantamine have been approved for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease, while donepezil has been approved for all stages (38). Memantine is the first NMDA receptor antago¬nist approved by the FDA for use in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. This drug has several mechanisms of action, but it is thought that modulation of the glutamatergic system, specifically the blockade of current flow through NMDA receptors, is the primary therapeutic action in Alzheimer’s disease. Memantine reduces neuronal excitotoxicity by modulating the tonic (i.e., mild, continuous, chronic) activation of NMDA receptors, which should be acting in a phasic manner (i.e., reacting to stimulus). There is some evidence that beta-amyloid toxicity is also reduced by high doses of memantine. Other neuro-protective drugs have been unsuccess¬ful in clinical trials due to intolerable side effects and inefficacy. Medications such as antidepressants and anti-anxi¬ety agents may be appropriate for some people to alleviate symptoms of concomitant depression and anxiety. A 2011 meta-analysis found that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors sertraline and citalopram were more effective than placebo at controlling agitation in dementia patients and may be better tolerated than antipsychotics (39). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are recom¬mended over tricyclic antidepressants when use of an antidepressant is indicated. Many women experience some form of sexual dysfunction – that is, a sexual problem that they find distressing. Yet, both patients and health providers may be reluctant to initiate a sexual health dialogue. Successful identification and resolution of female sexual disorders is not possible, however, if clinicians do not first ask about a woman’s sexual health. Definitions The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), recognizes six female sexual disorders: hypoactive desire disorder (HSDD); sexual aversion disorder, sexual arousal disorder, orgasmic disorder, dyspareunia, and vaginismus (16). In 2008 study Prevalence of Sexual Problems Associated with Distress (PRESIDE) furthered this research, categorizing female sexual disorder prevalence by age (17). Women aged 18 to 59 years, 43% reported having sexual problems within past year. The result of this survey of more than 31,000 women showed that midlife women have the highest rates of HSDD (12.3%) compared with younger women (9%) and women aged 65 years and older (7.4%). The authors speculate that a woman’s expectation of continued spontaneous sexual desire may contribute to the higher level of self-reported dysfunction among mid-life women compared with older women (17). Because many of the six female sexual disorders overlap, it is important to determine the primary disorder; and then how comorbid female sexual disorders develop overtime, a 1- to 2- minute assessment is generally sufficient to make a differential diagnosis. Asking the patient what she considers to be her primary sexual concern is a good place to start. For example, a patient may disclose having persistent, distressing, HSDD; careful follow-up questioning may reveal that pain during intercourse has caused or contributed to the decline in desire. Dyspareunia, therefore, and not HSDD, is likely the primary female sexual dysfunction. HSDD is defined as the persistent or recurrent deficiency of absence of sexual thoughts, fantasies, and/or desire for, or receptivity to, sexual activity, with causes marked personal distress or interpersonal difficulties (20). Sexual desire is at the center of the human sexual cycle, and HSDD is a common female sexual dysfunction. Diagnosis of HSDD is made when lost sexual desire causes personal distress and the patient complains. HSDD is consequential to genetically linked decline in circulating androgens from adrenal reticularis zone atrophy and ovulatory failure from menopause (18). In older women, whose androgen production is at a lifetime low, HSDD is diagnosed frequently as an isolated event, with prevalence approaching 50% in this population. Transdermal testosterone, even in modest doses, is highly effective in randomized prospective trials that involve older (postmenopausal) women who normally have low levels of circulating testosterone <20 ng/dL (19). In reproductive-aged women, whose androgen production is at a lifetime high, HSDD is diagnosed infrequently as an isolated event. Rather, HSDD in younger women is often linked to situational circumstances, dysfunctional interpersonal relationships, chronic disease, depression, drugs, gynecologic disorders, or other mitigating factors. In general, treatment of these mitigating factors is the best strategy for treating HSDD in the reproductive-aged group. Testosterone, unless administered in pharmacologic doses, is not usually effective in treating HSDD in reproductive-aged women. In one exception – oophorectomized women – the response to testosterone is similar to the postmenopausal population (18). HSDD is the most complex and poorly understood sexual dysfunction. Some women have never felt sexual desire or excitement. Others have had normal desire for sex in the past but no longer do. Defining desire is a good place to start. Although desire appears to be simple, universally understood word, it is considerably complex. In order to understand HSDD and to determine the appropriate treatment approach, it is helpful to divide desire into 3 components: drive, cognition, and motivation. Distinguishing among the components of desire is essential when assessing sexual problems, because treatment may differ greatly depending on which component(s) of desire have declined. For example, anger with the sexual partner can easily hamper a woman’s strong biological sexual drive. Alternatively, a woman with low biological drive and high motivation for partner intimacy can have a satisfying sex life despite few physical cues or sexual interest. Loss of estrogen In addition, other physiologic changes related to estrogen deficiency (e.g. reduced peripheral blood flow, reduced nerve transmission, sleep disruption, and mood alterations) may negatively affect sexual functions (22). Genital atrophy Progestogens Medications Associated with Low Sexual Desire Patient barriers Physician barriers Personal barriers to physician initiation of sexual health discussions with patients may include lack of privacy, cultural/language barriers, male gender, or personal discomfort discussing sex. The diagnosis of HSDD is largely made based on the medical interview. Estrogen and testosterone levels alone are insufficient to make a definitive diagnosis of HSDD. Sexual History Taking Open-ended, ubiquity-style questioning is recommended. A physician may begin the screening with a question that relates to other medical issues a patient may have, such as: Use simple, direct language combined with empathetic and normalizing statement. Declaring and demonstrating a lack of embarrassment and the willingness to listen may also improve disclosure. In addition, be aware of the patient’s cultural background, ensure confidentiality, and avoid making assumptions or being judgmental. The Narrative Thread When eliciting the narrative, continue – “go on” and “tell me more” – and emotionally supportive statement – “that sounds frustrating” – can facilitate the dialogue and reveal more details about the nature of the sexual problem. Lastly, try asking for clarification to confirm understanding: “So are you saying that you think your relationship with your partner might be the problem?” Although many women with HSDD will have normal findings, a physical examination may be warranted in some cases to identify possible contributors to low desire. The gynecologic examination can be particularly informative. The presence of vulvovaginal atrophy may result in dyspareunia, which can negatively affect sexual desire. Other important findings may include genital sensory changes (vulvodynia or neuropathy), pelvic floor muscle contraction (vaginismus), and pelvic floor prolapse, all of which can contribute to sexual dysfunction. Laboratory evaluation is rarely helpful in the diagnosis of low desire; however, it should be considered as warranted by history and physical examination. Women with physical findings suggestive of hyperprolactinemia or thyroid disease should have prolactin levels and thyroid function tests measured, respectively. Androgen levels alone are not meaningful, because levels have not been shown to correlate with sexual function. Furthermore, the testosterone assays that are currently used are unreliable at the lower levels seen in women. Psychotherapy, sex therapy, and pharmacologic therapy – or a combination thereof, may be effective in treating HSDD and other female sexual dysfunctions. Currently, no pharmacologic therapies are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of HSDD. Some treatments have been used off-label, however, in postmenopausal women. Psychotherapy Estrogen therapy Androgen therapy Pros: There is little information on transdermal testosterone in reproductive-aged and postmenopausal women and it is generally considered ineffective. Transdermal testosterone is more likely to be effective in patients who are testosterone-depleted (i.e. whose total serum testosterone is under 20 ng/dL). The following three circumstances may be the indication for testosterone use in reproductive-aged and postmenopausal women complaining of HSDD: Cons: When a woman complains about low desire, clinicians may assume that the problem occurs across all situations in her life, yet a careful interview often reveals that the right sexual partner or fantasy can evoke desire. Until the recent wider use of liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry to measure androgens in women, available assays were not accurate enough to compare women with normal desire to those with low desire. A recent cohort study using mass spectrometry failed to find any significant hormonal differences between normal- and low-desire women (27). However, psychosocial factors including anxiety, depression, and negative sexual experiences in childhood are clearly linked to women’s desire (28). Among more than 1,000 premenopausal women with HSDD in a large registry, dissatisfaction with appearance, stress, fatigue, and dyspareunia were commonly cited as contributing to the problem (27). Most clinical trials of testosterone replacement for women with low desire have focused on naturally or surgically postmenopausal women, but in a few studies, testosterone was administered to premenopausal women (28). Double-blinded randomized trials of testosterone as a treatment for low desire in women generally have four fatal flaws: 1) women in trial have very mild problems with sexual desire compared to clinical populations; 2) only the highest doses of testosterone are better than placebo, but these doses also raise serum testosterone to supra-normal levels; 3) the placebo effect is strikingly large; and 4) women are never debriefed about their confidence that they are in the active drug versus placebo arm, yet are repeatedly asked to fill out checklists highlighting symptoms such as acne or clitoral enlargement that might indicate that they are taking testosterone. If women can guess their treatment group correctly, their different expectations probably account for the small gap in efficacy between active drug and placebo (29). A recent trial of the antidepressant flibanserin in premenopausal women with low desire suffers from very similar methodology limitations (30). Testosterone therapy could increase their risk of breast cancer (29). Androgens are not always anti-proliferative in breast tissue, but promote growth in a subset of breast tumors that have androgen receptors. In both the Nurses’ Health Study II and the New York University Study, higher endogenous serum testosterone in premenopausal women is associated with increased risk of invasive breast cancer (31). Ospemifene Bupropion Other potential treatments on the horizon Other pharmaceutical agents in development include novel combination drugs that contain sublingual testosterone with a phosphodiestrate inhibitor (Lybrido) or a 5HT1A receptor agonist (Lybridos). Both are proposed to increase sexual motivation through testosterone; however, the addition of the phosphodiesterase inhibitor is thought to increase sexual physiological (vascular) sexual response, whereas addition of a 5HT1A receptor agonist is thought to act centrally by decreasing sexual inhibition. Bremelanotide, melanocortin receptor 4 agonist, is another agent that is being investigated for treatment of low desire and is also postulated to work through central nervous system mechanism (35). Patients and their clinicians can be reassured that for the majority of women, cognitive function is not likely to worsen in postmenopause in any pattern other than that expected with normal aging. Although it is not likely that in postmenopause, a woman’s cognitive function will return to what it was premenopause, she may adapt to and compensate for the symptoms with time. Sexual concerns should be addressed routinely as part of all comprehensive women’s health visits. Gynecologists are often the first health care provider a woman turns to when seeking help for sexual problems. It is important to provide a safe and non-judgmental environment that facilitates discussion of these issues. Placing patient-friendly educational material in waiting and examination rooms and training staff to be knowledgeable and comfortable with sexual topics can create an atmosphere that is conducive to discussing sexual issues. Intake forms can be modified to include questions about sexual health, which provide additional opportunities for patients to disclose their sexual concerns. Women should be reassured that discussions will remain confidential. The incidence of Alzheimer’s disease continues to rise. It is a difficult disease to treat medically and handle emotionally. This review presents some of the ele¬ments of pathology, medical treatment, and care of victims of this progressive disease. It is hoped that the continued research into the causes of Alzheimer’s disease will provide some of the necessary information about the prevention and treatment of this relentless and socially damaging disease. Decreased sexual desire is common among women of all ages and can have negative effects on overall well-being. As frontline providers of women’s health care, gynecologists are in a unique position to effectively diagnose and treat this condition. Sex education, office-based counseling, and medications (including bupropion and testosterone) are viable options in appropriate candidates. Difficult cases warrant referral to specialists in sexual health and medicine. Although there are not any FDA-approved medications for treatment of low sexual desire, several agents are in development. The complex etiology of low desire often dictates the need for a multifaceted intervention that uses a biopsychosocial approach. The popular media and society are often sources of misinformation and distorted ideas about sex. Health providers must be ready to identify and dispel myths about sex that can negatively influence sexual behavior. Опубликован: 13 April 2015

Positron emission tomography (PET) / computerized tomography (CT) scan of MCI and Alzheimer’s disease.

Photographs courtesy of Natasha McKay, M.D., Department of Neurosurgery, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA (USA)

Overview of Major Forms of Dementia:

Manifestations

Parkinsonian symptoms;

REM sleep disorder;

Hallucinations;

Apathy.Laboratory Work-up

A. Normal Brain Imaging; B. Mild parenchymal volume loss in MCI; C. Parenchymal volume loss in Dementia; D. Parenchymal volume loss in Alzheimer’s Disease.

Photographs courtesy of Rashmi Balasubramanya, M.D., Department of Radiology, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA (USA)

Alzheimer’s disease

Ten Warning Signs of Alzheimer’s disease:

Normal Aging Events

Possible Alzheimer’s disease

Temporarily forgetting someone’s name

Not being able to remember the person later

Forgetting the carrots on the stove until the meal is over

Forgetting a meal was ever prepared

Unable to find the right word, but using a fit substitute

Uttering incomprehensible sentences

Forgetting for a moment where you are going

Getting lost on your own street

Talking on phone, temporarily forgetting to watch a child

Forgetting there is a child

Having trouble balancing the checkbook

Not knowing what the numbers mean

Misplacing a wristwatch until steps are retracted

Putting a wristwatch in a sugar bowl

Having a bad day

Having rapid mood shifts

Gradual changes in personality with age

Drastic changes in personality

Tiring of housework, but eventually getting back to it

Not knowing or caring that housework needs to be done

MANAGEMENT

MANAGING FEMALE SEXUAL DISORDERS

A brief guide to female sexual dysfunction (DSM-5):

Female Sexual Dysfunction

Definition

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD)

Deficiency or absence of sexual thoughts, fantasies, and/or desire for, or receptivity to, sexual activity.

Sexual aversion disorder

Extreme aversion to; and avoidance of, all (or almost all) genital sexual contact with a partner.

Sexual arousal disorder

Inability to attain, or to maintain until completion of the sexual activity, adequate lubrication-swelling response of sexual excitement.

Orgasmic disorder

Delay in; or absence of, orgasm following a normal sexual excitement phase.

Dyspareunia

Any urogenital pain that interferes with sexual and non-sexual activities.

Vaginismus

Difficulty allowing vaginal entry of a penis, finger, or any object despite the express wish to do so; may include problems with muscle tension, anticipatory fear of pain, or avoidance behavior.

PREVALENCE

Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD)

Causes of Diminished Desire in Women

Estrogen deficiency, whether natural or resulting from surgical menopause, has long been associated with altered sexual function in women due to the following urogenital anatomical changes that it may induce (21):

All women with prolonged estrogen deficiency will experience some degree of genital atrophy. Epithelial changes occur in weeks to months, whereas vascular, muscular, and connective tissue changes become evident over the course of years. These changes can lead to vaginal dryness, decreased lubrication, loss of elasticity, dyspareunia, and distention of the urinary meatus, as well as urinary urgency, frequency, nocturia and dysuria. The possibility of genital atrophy and dyspareunia should be investigated thoroughly in postmenopausal women who desire low sexual desire.

Evidence demonstrates that progestogens may also contribute to sexual dysfunction by inhibiting androgen binding, inhibiting 5α-reduction of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the mood-dampening effects of progestins, and causing down-regulation of the estrogen receptor (21).

Barriers to Communication Regarding Female Sexual Problems

This multicenter study concluded 85% of adults wanted to discuss sexual functioning with their physician, many did not: 77% believed no treatment was available, 71% felt their physician did not have time, and 68% thought their physician would be embarrassed (22). Patients continue to be reluctant to initiate sexual health conversations with their healthcare provider. In a more recent study of mature, sexually active women aged 40 to 80 years, 43.9% had not sought clinical help for a sexual problem. Only 16% had spoken to a physician, and nearly 80% sought no medical help. Likewise, of the women with sexual problems and distress identified in the PRESIDE study, 34% had discussed the problem with a healthcare provider, and 41.5% had discussed it with a non-healthcare provider. Some sought help from anonymous sources such as the Internet, while 14% sought no help at all (17). According to the PRESIDE study, women are less likely to bring up sexual concerns with medical staff if they are single or have poor self-assessed health or moderate embarrassment. It is interesting to note the few women (12%) cited self-embarrassment as a sex discussion barrier, whereas 68% cited physician embarrassment.

One of the most significant practice barriers to physician initiation of sexual health discussions with patients is lack of knowledge/training in sexual medicine (23). A study of 53 University of Virginia medical students revealed that less than 10% felt confident in making a diagnosis of HSDD. However, nearly all of the respondents considered HSDD an important diagnosis to make (23). Other practice barriers include:

Effective Screening Techniques for Female Sexual Dysfunction

Several studies suggest that older women rarely initiate sexual health conversations with a healthcare provider, and that a large number would prefer their healthcare provider to do so. It is clear that screening sexual histories greatly improve the detection and successful resolution of sexual problems. In one study, physician questioning increased patient reporting of sexual dysfunction from 3% to 19% (24).

Open-ended questions that focus on the topic but do not prescribe the response require narrative elaboration; they can open the door to information, understanding, and feelings. Open-ended dialogue can also be efficient. In eliciting the patient’s narrative of sexual concerns, listen for critical elements in the patient’s speech and ask a directed, open-ended question to follow the narrative thread. Following are the examples:

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OPTIONS

Sex therapy is a specialized type of psychotherapy that can be prescribed when a patient’s chief concern is sexual. It often does not focus solely on sexual function but is based on the premise that sexuality is best understood within a biopsychosocial model. Sex therapy tends to be short term (5-20 sessions) and solution focused. Successful treatment is not limited to adequate genital functioning but also encompasses the patient’s psychological satisfaction.

Vaginal lubrication and atrophic conditions consistently improve with estrogen, as does vaginal blood flow, leading to increased arousal. With oral estrogen therapy, the gastrointestinal system and liver are exposed to high concentrations of estrogen before it enters the bloodstream. This alters hepatic metabolism and can result in increased triglycerides, C-reactive protein, sex hormone-binding globulin, and clotting factors. In contrast, non-oral estrogen therapy (i.e. patch, gel, or vaginal ring) – bioidentical estradiol – is first absorbed into the peripheral circulation, thereby reducing the overall impact on liver metabolism. All commercially available vaginal estrogens effectively relieve common vulvovaginal atrophy-related complaints and have additional utility in patients with urinary urgency, frequency or nocturia, stress urinary incontinence and urgency urinary incontinence, and recurrent urinary tract infections. Non-hormonal moisturizers are a beneficial alternative for those with few or minor atrophy-related symptoms and in patients at risk for estrogen-related neoplasia (25).

Testosterone levels do not drop as precipitously as estrogen levels do during menopause; however, they do gradually decline with age. The North American Menopause Society guidelines point to the increased sexual desire evidenced studies examining the benefit of adding testosterone to estrogen therapy in select patients with HSDD (26). However, because long-term safety data are lacking, the Endocrine Society recommends against generalized use of androgen therapy. Pros and cons of testosterone therapy:

Ospemifene is FDA approved treatment for dyspareunia, which can contribute to low or absent desire. It is a novel selective estrogen receptor modular with indication for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy and dyspareunia in postmenopausal women. A daily dose of 60 mg has been shown to be effective and safe with minimal side effects (32). This treatment can be useful in women who have secondary hypoactive sexual desire as a result of vaginal atrophy and dyspareunia. The ospemifene endometrial profile, including histology and ultrasonography results for a maximum of 1 year of daily oral treatment, appears more consistent with the selective estrogen receptor modulator raloxifene than with steroidal estrogen. Histology, transvaginal ultrasonography greater than 5 mm, and symptoms of vaginal bleeding were helpful in discerning endometrial safety.

Bupropion is a mild dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist that is used as an antidepressant and smoking cessation aid. In a single-blind study of 51 non-depressed women, 29% responded to treatment with bupropion SR (33). A subsequent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of bupropion (150 mg/day) in 232 premenopausal women without depression also showed a significant increase in desire and decrease in distress in the treated group (34)). In addition to the treatment of non-depressed women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder, bupropion has been shown to be effective in reversing selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction in premenopausal women.

There are several pharmacologic treatments in development. Flibanserin is a 5-HT1A receptor agonist and 5-HT2 receptor antagonist that has been studied in more than 11,000 women. Phase III trials have shown 100 mg flibanserin nightly to improve sexual desire, decrease distress, and increased the number of satisfying sexual events. A new Drug Application for treatment for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women was rejected by the FDA in October 2013. A subsequent appeal through a formal dispute resolution has led to additional safety studies currently underway and a resubmission is planned in the spring of 2015.SUMMARY

Suggested Reading

http://www.womenshealthsection.com/content/gyn/gyn008.php3

http://www.womenshealthsection.com/content/gyn/gyn032.php3References

Dedicated to Women's and Children's Well-being and Health Care Worldwide

www.womenshealthsection.com