Global Efforts to End Obstetric Fistula (Part 2)

WHEC Practice Bulletin and Clinical Management Guidelines for healthcare providers. Educational grant provided by Women's Health and Education Center (WHEC)

An obstetric fistula, or abnormal opening between the vagina and the bladder or rectum, is a devastating condition. It is caused by prolonged labor: the fetus’ head compresses soft tissues of bladder, vagina, and rectum against the woman’s pelvis, cutting off blood supply, causing these tissues to die, and slough away. It can result in urinary or fecal incontinence or both; concomitant conditions may include painful rashes resulting from constant urine leakage, amenorrhea, vaginal stenosis, infertility, bladder stone and infection (1). Women having obstetric fistula may be abandoned by their husbands and ostracized by their communities. Although global prevalence is unknown, the self-reported lifetime prevalence of fistula symptoms reported in Demographic and Health Surveys has ranged from 0.4% in Nigeria (2) to 4.7% in Malawi (3). Less frequently, genitourinary and rectovaginal fistulas may result from sexual violence, malignant disease, radiation therapy, or surgical injury (most often the bladder during hysterectomy or cesarean section). Surgical injury, malignant disease, and radiation therapy are the predominant cause of the condition in industrialized countries; indeed, obstetric fistula rarely occurs in settings where competent emergency obstetric care is readily accessible. Fistulas resulting from surgical injury are characterized by discrete wounding of otherwise normal tissue, whereas both obstructed labor and radiation may lead to extensive ischemia and scarring. There are two broad research priorities in the vaginal fistula (hereafter referred to as “fistula”) repair field. One it to evaluate which operative techniques and methods of perioperative patient management are most effective and efficient for fistula closure and prevention of residual incontinence after successful closure. Many fistula surgeons have developed their own methods through experience and thus a wide variety of procedures and methods are commonly used (4). The other need is for evidence to support the development of a standardized evidence-based system for classifying fistula prognosis, and at a minimum, a system prognostic for fistula closure. To develop a prognostic system, it is necessary to determine which patient and fistula characteristics independently predict outcomes, and to identify the minimal parameters required for accurate prognosis, because the simpler a classification system, the more likely it is to be used (5). A prognostic classification system would not only facilitate the evaluation of surgical success rates across facilities, but also the effectiveness of interventions independent of confounding by patient or fistula characteristics; it would also facilitate the comparative analysis of studies that examine treatment outcomes.

The purpose of this document to review the global efforts to end obstetric fistula and recommend effective delivery care in developing countries and awareness of the magnitude of this catastrophic childbirth injuries. Almost all obstetric fistulae occur in resource-poor areas, as a paucity of resources is the root cause. Where there are no suitable facilities for deliveries and obstetric emergencies, obstruction of labor often results in fetal death and obstetric fistula. Treatment in this setting usually focuses on meeting patients’ immediate needs rather than conducting research and refining techniques and long-term management of the patients. Unified, standardized evidence-base for informing clinical practice is lacking. This review addresses the efforts of the United Nations and its Member States and remaining gaps.

Actions taken by Member States and the United Nations and remaining gaps:

Prevention strategies and interventions to achieve maternal health goals and eliminate obstetric fistula

Research shows that averting maternal death and disability, including fistula, is accomplished most effectively when universal access to three key interventions is ensured, namely, family planning, skilled birth attendance at every delivery, and access to emergency obstetric and newborn care. To accelerate progress in maternal and newborn health and boost support to high maternal mortality countries, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) launched the Maternal Health Thematic Fund and the Global Programme to Enhance Reproductive Health Commodity Security (6). The Maternal Health Thematic Fund supports the global Campaign to End Fistula and national fistula programmes in priority countries. In regions with high maternal mortality and morbidity, the proportion of births attended by skilled health professionals has risen from 55 per cent in 1990 to 65 per cent in 2009, with vast disparities across regions and the lowest levels of skilled care in Africa and South Asia. Midwives play a crucial role in preventing obstetric fistula by providing high-quality skilled delivery care, identifying when a woman’s labor is prolonged or obstructed, through tools such as the partograph, and referring her to an obstetrician, gynecologist or doctor when emergency obstetric care or Caesarean section is required (7). Midwives and doctors are vital to ensuring early management of new fistulas, as is referring women suffering from fistula to trained, expert fistula surgeons for care.

Several countries in Africa and Asia have taken steps to improve access to services by reducing or removing user fees for basic health care. Sierra Leone launched a major initiative in 2010 to provide free health care for pregnant women, lactating mothers and children under 5. Togo subsidizes 90 per cent of the cost of Cesarean sections since 2011. Bangladesh piloted a voucher scheme encouraging women to access antenatal and delivery services. Countries should ensure free or subsidized maternal health care for all poor women and girls who cannot afford it. To intensify support to countries with some of the highest numbers of maternal and newborn deaths, in line with the Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health, the “H4+” health agencies (UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN-Women, World Bank, WHO) launched the High Burden Country Initiative. The Initiative supports health system strengthening in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, Mozambique, Nigeria and the United Republic of Tanzania, which account for nearly 60 per cent of global maternal and newborn deaths. Access to services – particularly skilled birth attendance and emergency obstetric care – is the greatest challenge in preventing maternal mortality and morbidity. Maternity waiting homes, low-cost or free accommodations located near or in a health facility, are a promising option to help bridge the geographical gap in access to care (8). They allow rural and “high risk” women to await delivery and, when labor begins, or earlier in case of complications, to be transferred to a medical facility nearby. They are also crucial to helping ensure access to elective Cesarean sections for fistula survivors who become pregnant again, to prevent fistula recurrence and increase the chances of survival of mother and baby. Although more evidence is needed, maternity waiting homes can have a positive impact on rural women’s health and help to reduce maternal and newborn deaths and disabilities, as demonstrated in Cuba, Eritrea, Nicaragua and Zimbabwe.

Access to family planning helps to ensure that every pregnancy is wanted, planned and occurs at an optimal time in a woman’s life. It is essential in reducing the risk of recurrence of fistula in future pregnancies of fistula survivors. UNFPA has advocated for building and maintaining political and financial commitment to family planning within maternal health strategies. In 2011, UNFPA supported the regional Conference on Population, Development and Family Planning in Francophone West Africa, held in Burkina Faso, and the International Conference on Family Planning in Senegal. The UNFPA Global Programme to Enhance Reproductive Health Commodity Security has mobilized $450 million since 2007 to ensure reliable supplies of contraceptives, condoms and medicines. While preventing fistula from occurring is a top priority, it is essential not to forget treated fistula survivors who may be at risk of a further obstructed labor, and a new fistula, or even dying in subsequent pregnancies. This is an often overlooked, yet critical issue, on which the Campaign to End Fistula is placing new emphasis to ensure the survival of mother and baby and prevent recurrent fistula, through elective Caesarean sections for fistula survivors. This remains a neglected issue, however, and requires significantly intensified commitment and action.

Community sensitization and mobilization are key components of preventing obstetric fistula and maternal deaths. Fistula survivors can play a vital role as advocates in raising awareness about the need for timely antenatal, skilled delivery, and post-partum care. The United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on Adolescent Girls, in 2010, signed a joint statement to increase support to developing countries to advance key policies and programmes to empower the hardest-to-reach adolescent girls. To date, 20 countries have received support in planning comprehensive programmes addressing vulnerable girls.

Treatment Strategies and Interventions:

Although prevention is the ultimate means of eliminating obstetric fistula, treatment is critically important for women living with the condition as it enables them to reclaim their lives, hopes and dignity. Countries have increased access to fistula treatment through upgrading health facilities and training health personnel. In 2011, significant progress was made to scale up treatment, and more than 7,000 fistula surgeries were directly supported by UNFPA, a 40 per cent increase from 2010. Hundreds of thousands of women and girls worldwide still await treatment, however, and global treatment capacities are severely deficient in reaching and healing them all. A tremendous backlog of patients continues to grow. A dramatic and sustainable scaling-up of quality treatment services and trained fistula surgeons is needed. Closing this gap is an important challenge currently facing countries and the Campaign to End Fistula. Many poor women and girls cannot afford fistula treatment despite the fact that some countries now offer fistula treatment at no cost. Therefore, all countries should ensure access to free fistula treatment services. There is an urgent and ongoing need for committed national and donor support to provide the resources necessary to reach all women and girls suffering this condition. Increased multi-year commitments are critical to ensure sufficient, sustainable and continued programming.

Many women and girls living with fistula are not aware that treatment is available. For those who are, a major obstacle in accessing fistula repair services is the high cost of transportation to health facilities, particularly for those living in remote areas. In the Sudan, geographical accessibility was improved by locating fistula repair services close to remote communities. In 2011, the Aberdeen Women’s Centre, Sierra Leone, set up a special toll-free hotline to provide information and care options for women with fistula, enabling over 220 patients to get treatment. Comprehensive Community-based Rehabilitation in the United Republic of Tanzania and the Freedom from Fistula Foundation in Kenya provide free fistula repair surgeries and developed a mobile telephone initiative to help those who cannot afford transportation costs. Using M-Pesa mobile-to-mobile banking technology, funds are transferred to fistula patients to cover transport costs. To facilitate access to fistula treatment services and improve quality of care, many countries, such as Angola and Yemen, are integrating fistula services into strategically selected hospitals, shifting away from the “mission or camp” approach for treating fistula. While intermittent missions or camps provide surgical repairs to high numbers of women, and are useful for training fistula surgeons, they have limited scope and potential. Moving forward from the mission/camp approach, countries should strive to establish integrated fistula services in strategically selected hospitals which are continuously available and provide the full continuum of holistic care and support for treatment, rehabilitation and crucial follow-up for fistula sufferers.

To improve the quality of care and ensure that all women receive the best treatment possible, the International Society of Obstetric Fistula Surgeons, promotes knowledge-sharing, professional development and quality assurance among fistula surgeons and health-care providers. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, with support from UNFPA and the International Society of Obstetric Fistula Surgeons, developed a competency-based training manual on obstetric fistula to harmonize surgical approaches and techniques among fistula centers. UNFPA is developing a supplementary document for Campaign to End Fistula partners and ministries of health that gives strategic recommendations on training fistula surgeons. Quality assurance remains a challenge. One primary concern is that many trained health providers in fistula management have limited support to practice their skills. Intensified efforts are needed to ensure that trained personnel have optimal working conditions, fully-equipped, functional health centers and incentives to retain them to provide fistula repairs. Ensuring that providers respect pre-operative criteria, including patients’ adequate nutritional status and fitness for surgery, to optimize surgical outcome, is also a challenge.

Reintegration Strategies and Interventions:

Healing fistula requires not only surgical intervention but also a holistic approach, including psychosocial and economic support. Previously, very few countries reported on women who received reintegration on rehabilitation services, a key component of the continuum of care. In 2012, about 19 countries, including Afghanistan, Cameroon, Guinea-Bissau and Nepal, reported providing such services, reflecting increased commitment. However, follow-up of fistula patients is a major challenge. In most countries, only a fraction of fistula patients are offered reintegration services, despite significant needs. All fistula-affected countries should track this indicator to ensure access to reintegration services. Intensive social reintegration for inoperable or incurable fistula patients remains a major gap.

Reintegration services include counseling – throughout all phases of treatment and recovery, from the first point of contact, through post-discharge from hospital, reproductive health education, family planning, and income-generating activities, combined with community sensitization to reduce stigma and discrimination. In Pakistan, four fistula centers offer rehabilitation activities for fistula patients, including Koohi Goth Hospital in Karachi, started by a local doctor, Shershah Syed. Over 70 patients received rehabilitation support in 2011, with periodic follow-up to evaluate the impact. Connecting fistula patients to income-generating activities provides a much needed livelihood, renewed social connections and sense of purpose. In the Congo, treated fistula patients are provided with a tutor to help create a business based on existing or desired skills. Patients are entitled to a bank account and training in business and financial literacy. Fistula Foundation Nigeria supports women with inoperable or incurable fistula with a training programme in various trades including embroidery, knitting and photography. In Ethiopia, a partner of the Campaign to End Fistula, Healing Hands of Joy, is implementing an innovative model of healing, empowerment and reintegration for fistula survivors, trained as “safe motherhood ambassadors”. Despite these good practices, too few fistula survivors benefit from such vital socioeconomic reintegration services.

Data Collection and Analysis:

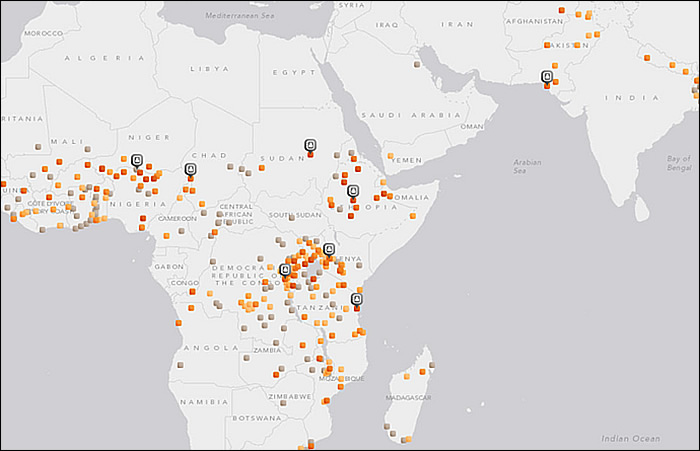

Information on fistula-related activities is scarce, scattered, incomplete and difficult to obtain. Concerted efforts have been made to improve availability of data, including the launching of the first Global Fistula Map early in 2012. A standardized fistula module for inclusion in demographic and health surveys has been developed and used in Cameroon, Guinea and Guinea-Bissau. The Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research and WHO developed an online database that allows centralized data entry, analysis and comparison across programmes. Burkina Faso and Ghana have included fistula in their national health information systems. Development of a compendium of indicators is ongoing to assist countries in selecting key indicators to monitor their fistula programming. Obtaining data remains a challenge, owing to inadequate data recording and reporting systems.

The Global Fistula Map will help to streamline the allocation of resources, raise awareness of fistula, and capture the landscape of worldwide fistula treatment capacity and gaps. Tragically, in the countries with the highest levels of maternal deaths and obstetric fistula, such as Burundi, Chad, the Central African Republic, Somalia and South Sudan, the map reveals the greatest gaps, with a severe lack of fistula treatment centers. It highlights the tremendous efforts made by many partners to treat fistula, and can be used as a tool to facilitate South-South collaboration. Data gathered shows that, while the availability of surgical treatment for fistula is growing, only a fraction of fistula patients receive treatment annually. More than half of reporting facilities treated fewer than 50 patients each in 2010. Only five facilities worldwide each reported treating over 500 women. The map will be expanded and continuously updated with information provided by experts and practitioners around the globe about fistula repair and rehabilitation services.

Maternal death and near miss (9) reviews are an increasingly recognized and utilized means to improve quality assurance. Maternal death surveillance and response was adopted by partners as a framework towards maternal mortality elimination as a global public health burden. Inter-agency consultations, as part of the Commission on Information and Accountability, have been organized in all regions, addressing needs for the institutionalization of maternal death reviews and maternal death surveillance and response. Benin, Burundi, Ethiopia, Ghana, Madagascar and Malawi are moving towards systematic maternal death audits to improve quality of care. In Bangladesh and Nepal, a national surveillance system is being initiated, with UNFPA support, to identify and treat “hidden” fistula cases.

In partnership with United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization (WHO) and the Averting Maternal Death and Disabilities Programme of Columbia University, New York, UNFPA supported emergency obstetric and newborn care needs assessments in countries with high maternal mortality. The assessments map the current level of care and provide evidence needed for planning, advocacy and resource mobilization to scale up emergency services in every district. By 2011, about 24 countries had completed or initiated such assessments. Far more research is needed to effectively address the problem of obstetric fistula. Johns Hopkins University, with UNFPA and WHO, is conducting a multi-centric study to examine the links between surgical prognosis and treatment and long-term health, psychosocial and reintegration outcomes following fistula surgery. This landmark study, launched in 2010, is ongoing in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and the Niger. Study results will help to develop a prognostic-based classification system for obstetric fistula, guide advocacy and inform cost-effective programmes and national strategies. Progress is slow, however, for lack of funds.

Finding ways of providing fistula repair services efficiently and cost-effectively, without comprising surgical outcomes and the overall health of the patient, is paramount. The Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction of United Nations Development Program (UNDP), UNFPA, WHO and the World Bank, jointly with Engender Health, is conducting a facility-based multi-centre randomized controlled trial in some African countries to examine whether short-term (7-day) catheterization following surgical repair of “simple” fistula cases is inferior to longer-term (14-day) catheterization in terms of fistula repair breakdown.

As midwives are the “front-line workers” in the fight to prevent obstetric fistula and maternal mortality, a skilled midwifery workforce is vital. Data on midwifery in the hardest-hit countries is, however, lacking. To fill the data gap, the Midwifery Programme launched by UNFPA and the International Confederation of Midwives, in 2011 issued the first State of the World’s Midwifery report. This joint effort involved 30 global partners to generate data on midwifery workforce services and policies from 58 low-resource countries representing 91 per cent of the global burden of maternal mortality and 82 per cent of newborn mortality. Twenty-seven needs assessments and gap analyses were conducted and subsequent country action plans developed to strengthen midwifery policies and capacities (10).

Advocacy and Awareness-Raising:

National champions and global activists support the Campaign to End Fistula. The First Lady of Sierra Leone, Mrs. Sia Nyama Koroma, fistula survivor Sarah Omega from Kenya, Natalie Imbruglia and Christy Turlington Burns are among many advocates worldwide who continue mobilizing support. Policymakers, national and local religious and community leaders and health professionals have a critical role in advocating for the rights of women and girls, and challenging harmful practices and gender inequities that threaten their well-being.

The Campaign to End Fistula was one of a few initiatives featured in MDG Good Practices, a publication by the United Nations Development Group which highlighted the innovative, comprehensive programmatic and advocacy approach of the Campaign. This approach has the potential to be significantly magnified at the global level to further strengthen advocacy and awareness-raising for ending obstetric fistula and will require intensified mobilization of human and financial resources. Globally and nationally, there has been a stronger focus on coordinated advocacy and communication efforts to end obstetric fistula. However, developing the most high-impact, cost-effective and culturally appropriate means to convey health messages remains a challenge in many countries. Human rights concepts are key. Using the media, including social media, for awareness-raising and advocacy, utilizing radio, television and the press to send important messages on fistula prevention, treatment and social reintegration to effectively reach families and communities would narrow this gap.

Community-based communication and mobilization help to overcome barriers to obstetric fistula prevention and identify solutions that are culturally acceptable. One of the most innovative and successful approaches has been involving fistula survivors in community mobilization. There is no more powerful voice for promoting prevention and safe delivery, and helping “invisible” fistula survivors to access treatment, than a woman who has survived fistula. Eighteen countries have supported fistula survivors to sensitize communities, provide peer support and advocate improved maternal health at both community and national levels.

In 2011, for the first time in the history of the Campaign to End Fistula, fistula survivors participated in the annual meeting of technical experts of the International Obstetric Fistula Working Group, bringing a vital, yet previously missing, link to the table. This was not only a symbol of the international recognition of their valuable advocacy work with “One by one let’s end fistula” in Kenya, but, more importantly, a key contribution to programmatic and strategic efforts at the global level. As a result of continued efforts by the Campaign’s secretariat, many organizations are now working with fistula survivors and advocates to reach women and girls living with fistula, advocate for prevention, women’s empowerment, men’s engagement and political commitment to end fistula. In Bangladesh and the Niger, mobile telephones were provided to fistula advocates to improve coordination efforts and elicit greater involvement with communities in their villages.

Global Support and Resource Mobilization:

The Every Woman Every Child initiative aims to put the Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health into action. By February 2012, about 217 commitments had been made (11) (See commitments of Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC) below). Some countries made important commitments, including free Caesarean section in subsequent pregnancies of fistula survivors, establishment of treatment centers and free fistula services. More than 25 business organizations have made commitments to the Strategy, including the first grant from Johnson & Johnson to a joint United Nations programme in Ethiopia and the United Republic of Tanzania.

A major challenge facing countries is the insufficiency of national financial resources for maternal health and obstetric fistula. This problem is compounded further by low levels of official development assistance directed for Millennium Development Goal 5. Contributions to the Campaign to End Fistula are vastly insufficient to meet the needs globally, and have steadily declined in recent years, in part because of the ongoing global financial crisis. Thus, urgent redoubling of efforts is required to intensify resource mobilization to ensure that fistula does not once again become a neglected issue. Other initiatives that support maternal health and fistula prevention to accelerate the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals include the G-8 Muskoka Initiative on Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health, and the Health Eight.

Future Research Priorities:

We have identified several research priorities. First, the endpoint “any incontinence,” does little to inform intervention efforts, because the causes of failure to close a fistula vs. causes of residual incontinence cannot be teased out. Future studies should examine fistula closure and residual incontinence separately, to clarify the etiologic importance of different characteristics and procedures being studied. Where possible, studies examining residual incontinence should use urodynamic studies to enable differentiation between types of incontinence, including stress, urge, overflow, and mixed incontinence.

Secondly, post hoc studies of predictive value of an individual classification system cannot determine the sufficiency of the systems for predicting repair outcomes, or the superiority of one system of another. For instance, it is possible that patient or fistula characteristics not included in current classification systems are important in predicting repair outcomes. Similarly, the inability of any component of these systems to predict fistula closure may result from inadequate statistical power to detect small differences. To develop a single, standardized prognostic system for classifying fistulas, additional research confirming the prognostic value of parameters included in existing classification systems, as well as evaluating factors not included, is needed. It is also important to compare existing classification systems to assess their relative discriminatory value for predicting repair outcomes.

More research is also required to assess which perioperative factors are associated with repair outcomes, independent of patient or fistula characteristics. In particular, further research is required on factors such as duration of catheterization and route of repair that may be associated with increased hospital stay and risk of health care associated with infections. A standardized system of classifying fistula prognosis will facilitate the conduct of such studies (5,12). Given the material and human resource shortages in the settings in which fistula surgery is often conducted, it is admirable that any data has been accumulated on this patient population. Nonetheless, further research is urgently needed to improve the care and treatment of this marginalized and neglected group of women.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Specific, critical actions, within a human rights-based approach that must be urgently taken by Member States and the international community to end obstetric fistula include:

(a) Greater investment in strengthening health systems, ensuring adequately trained and skilled human resources, especially midwives, obstetricians, gynecologists and doctors, as well as investments in infrastructure, referral mechanisms, equipment and supply chains, to improve maternal health services and ensure that women and girls have access to the full continuum of care;

(b) Equitable access and coverage, through national plans, policies and programmes that make maternal health services, particularly family planning, skilled birth attendance and emergency obstetric and newborn care and obstetric fistula treatment geographically and financially accessible. Countries should ensure access, particularly in rural and remote areas, through the establishment and distribution of health-care facilities and trained medical personnel, collaboration with the transport sector for affordable transport options, and promotion and support of community-based solutions;

(c) Integration of fistula prevention and treatment and socioeconomic reintegration into national plans, policies, strategies and budgets, and systematic follow-up of fistula patients. States should ensure comprehensive multidisciplinary national action plans and strategies for eliminating fistula with emphasis on prevention. Emphasis must be placed on primary prevention at the levels of the law, policy and programmes. Women’s and children’s wellbeing and survival must be protected, including preventing recurrence of subsequent fistulas by making post-surgery follow-up and tracking of fistula patients a routine and key component of all fistula programmes;

(d) Increased national budgets for health, ensuring adequate funds allocated to reproductive health, including for obstetric fistula. Within countries, policy and programmatic approaches to redress inequities and reach poor, vulnerable women and girls must be incorporated into all sectors of national budgets. Countries should provide free or adequately subsidized maternal health care as well as obstetric fistula treatment for all women and girls in need who cannot afford it;

(e) Enhanced international cooperation, including intensified technical and financial support, in particular to high-burden countries, to accelerate progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5 and fistula elimination;

(f) Establishment or strengthening of a National Task Force for Fistula, led by the Ministry of Health, to enhance national coordination and improve partner collaboration;

(g) Ensuring access to fistula treatment through increased availability of trained, expert fistula surgeons as well as permanent, holistic fistula services integrated into strategically selected hospitals. This should be accompanied by quality control, and improved monitoring mechanisms to ensure that only trained, expert fistula surgeons provide treatment to address the significant backlog of women awaiting care;

(h) Developing a community- and facility-based mechanism for systematic notification of obstetric fistula cases to ministries of health, in a national register;

(i) Ensuring that all women who have undergone fistula treatment have access to social reintegration services, including counseling, education, skills development and income-generating activities. Countries should provide holistic services including intensive social reintegration support for the forgotten women and girls with incurable or inoperable fistula. Linkages with civil society organizations and women’s empowerment programmes should be developed to help to achieve this goal;

(j) Empowering women who are survivors of obstetric fistula to contribute to community sensitization and mobilization as advocates for fistula elimination and safe motherhood;

(k) Mobilizing communities and women in particular, to be involved, informed and empowered regarding reproductive health services and maternal health needs, utilization of services and support to women to access such services. Promoting the enhanced engagement of civil society and local religious and community leaders in raising awareness and reducing stigma, discrimination, violence against women and girls and harmful practices such as child marriage. Ensuring the involvement of men and boys as key stakeholders in advocating for and supporting women’s access to reproductive health care and rights, gender equity, ending violence against women and girls, and preventing child marriage, recognizing that the well-being of women and girls has a significant positive effect on the survival and health of children, families and societies;

(l) Strengthening awareness-raising and advocacy, including through the media, to effectively reach families and communities with key messages on fistula prevention, treatment and social reintegration;

(m) Strengthened and expanded interventions to keep girls in school, especially post-primary and beyond, end child marriage, and protect and promote gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. Laws prohibiting child marriage must be adopted and enforced, and followed by innovative incentives for families to avoid marrying girls off at early ages, including in rural and remote communities;

(n) Strengthening research, data collection, monitoring and evaluation to guide planning and implementation of maternal health programmes including obstetric fistula. Countries should conduct up-to-date needs assessments on emergency obstetric and newborn care and for fistula, and routine reviews of maternal deaths and near miss cases, as part of a national maternal death surveillance and response system, integrated within their national health information system.

As the Campaign to End Fistula approaches its tenth anniversary, the challenge of putting an end to obstetric fistula requires vastly intensified efforts at the national, regional and international levels. Such efforts must be part of the strengthening of health systems, gender and socioeconomic equality and human rights, aimed at achieving Millennium Development Goal 5. If Goal 5 is to be achieved, additional resources must be forthcoming to accelerate progress. Funding must be increased, predictable and sustained. Significantly increased support should be urgently provided to countries’ national plans, United Nations entities, including the Maternal Health Thematic Fund, the Campaign to End Fistula, and other global initiatives dedicated to achieving Millennium Development Goals 3 and 5 by 2015.

Suggested Reading:

- 1. World Health Organization / The Fistula Foundation

Global Fistula Map

http://www.globalfistulamap.org/ - 2. The UN Population Fund / UNFPA

Campaign to End Fistula

http://www.endfistula.org/public/

Funding:

Provided by Global Initiatives of Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC) and its partners to improve maternal and child health worldwide.

References:

- Wall LL. Obstetric vesicovaginal fistula as an international public health problem. Lancet 2006;368:1201-1209

- National Population Commission (NPC), ORC Macro. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Calverton, MD: NPC and ORC Macro; 2009

- National Statistical Office (NSO), ORC Macro. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004, Calverton, MD: NSO and ORC Macro; 2005

- Browning A. The circumferential obstetric fistula: characteristics, management and outcomes. BJOG 2007;114:1172-1176

- Frajzyngier V, Ruminjo J, Barone MA. Factors influencing urinary fistula repair outcomes in developing countries: a systemic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:248-258

- UNFPA / Maternal Thematic Fund; For every 500,000 population and every sub-national area or district, a minimum of five basic primary health facilities, with at least one of those facilities offering comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care

- Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2010; and The State of the World’s Midwifery 2011: Delivering Health, Saving Lives

- General Comment 14 of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights defines accessibility as having four overlapping dimensions: non-discrimination, physical accessibility, economic accessibility and information accessibility

- A near miss is commonly understood as a severe life-threatening obstetric complication necessitating an urgent medical intervention in order to prevent the likely death of the mother (WHO, Beyond the Numbers, 2004)

- 67th Session, Item 28 (a); Advancement of Women; Report of Secretary General; General Assembly resolution 65/188; Obstetric fistula

- 2011 Commitments with the UN to advance the Global Strategy for Women’s & Children’s Health; View the 2011 commitments to advance the Global Strategy for Women's and Children's Health at: www.everywomaneverychild.org/images/content/files/Commitment_Document_9_23_11.pdf

(Commitments of Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC) are mentioned on Page 30) - Kirschner C, Yost K, Du H, et al. Obstetric fistula: the ECWA Evangel WF Center surgical experience from Jos, Nigeria. Int Urogynecol J 2010;21:1525-1533

Published: 20 February 2013

Dedicated to Women's and Children's Well-being and Health Care Worldwide

www.womenshealthsection.com