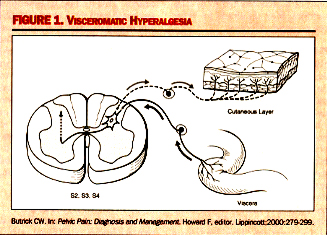

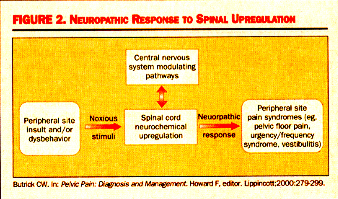

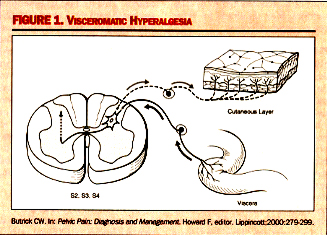

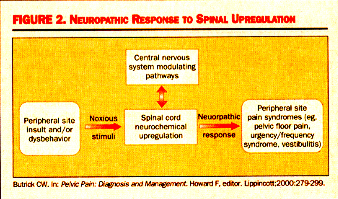

Interstitial Cystitis (IC): A Comprehensive ReviewWHEC Practice Bulletin and Clinical Management Guidelines for healthcare providers. Educational grant provided by Women's Health and Education Center (WHEC).Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a disease of the bladder characterized by urinary frequency and urgency, irritable voiding, and pelvic pain. It is a chronic, debilitating syndrome that occurs primarily in women and often presents with both urologic and gynecologic symptoms. The purpose of this document is to enrich the understanding of this condition among gynecologists and primary care physicians, to whom many patients with unidentified chronic pelvic pain initially present. Researchers have recently developed several tools to help clinicians make early diagnosis and offer effective treatment. Because this condition tends to develop very slowly, patients may not even be able to explain when it started. Moreover, symptoms occur on a continuum and may flare with sexual intercourse, allergies, menstruation, or stress. Fifteen percent of women in the United States (approximately 9 to 15 million) have consulted their gynecologists for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain (1). In approximately one third of these cases, an attempt has been made to treat the problem in the absence of any clear etiology- a practice that typically feeds, rather than stops the cycle of this disorder. The prevalence of interstitial cystitis is much higher than what is currently estimated in the literature. Individuals with chronic pelvic pain of bladder origin have interstitial cystitis, a disorder that may cause urinary urgency/frequency and/or dysparunia and/or intermittent or persistent pain in any number and combination of pelvic sites. Its psychological effects can be equally profound; indeed, this disorder is known to cause depression and social isolation. As clinicians with the responsibility of treating patient's pain, we must consider its diagnosis in women with chronic pelvic pain. The purpose of this document is to improve the necessary knowledge of healthcare providers to make the correct and early diagnosis of interstitial cystitis (IC). Also, even for clinicians who are aware of interstitial cystitis (IC), some patients present with atypical symptoms or co-morbid conditions that make the correct diagnosis challenging. It is also important to note that, whereas IC may present as urgency and frequency without pain, the presence of pain is required for the diagnosis. This review summarizes discussions of issues identified as being of concern in several surveys, interviews, and question-answer sessions at professional educational activities. Neuro-pathology of Interstitial Cystitis (IC): IC is thought to be derived from a defect in the protective glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer of bladder mucosal and by an increased number of activated bladder mast cells (2). Interstitial cystitis is not an end organ disease, but a visceral pain syndrome. Visceral pain syndromes involve chronic neurogenic inflammation, primary afferent over activity, and central sensitization, which all interact to perpetuate pain. For reason unknown, the protective GAG layer of the bladder is denuded in IC, allowing solutes such as potassium to filter across the usually impermeable uro-epithelium. The result is pain from nerve-ending excitation and ultimately, mast cell release. Degranulation of mast cells can occur due to and IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. This leads to a release of histamine, which causes localized pain and irritation in the tissue. Patients with IC also tend to experience conditions that are exacerbated by stress, such as allergies, irritable bowel syndrome, and migraines. The release of neuropeptides during stress may lead to local bladder mast cell secretion of vasoactive, pro-inflammatory, and noxious mediators substance P. Sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves merge in the pelvic ganglia. Parasympathetic neurons can carry noxious stimuli from the bladder going through segments S 2, 3, and 4 of the spinal cord, which is the same location of sensory innervation to the perineal area. Visceral afferent nerves can branch in the spinal cord to synapse with many dorsal horn cells in many spinal cord segments. In addition, nerves from multiple organs (eg, muscle, viscera, skin) can converge on a single dorsal horn neuron and affect each other, not only at that level of the dorsal horn, but also in the supraspinal levels as the second-order neurons travel in close proximity on the way to the cerebral cortex. This intermingling is important to enable the organs to communicate for normal and coordinated body functions. However, since the dorsal horn neurons are the heart of the communication system, anything that affects their function can have widespread effects (3).

Butrick CW. Pelvic Pain: Diagnosis and Management. Howard F, editor. Lippincott;2000:279-299. Viscerovisceral Hyperalgesia: This is a phenomenon in which pain from one organ can induce pain and dysfunction in another. In this hyperalgesic reflex, one organ is the original organ that is inflamed, such as the bladder. As a reflex of hyperalgesia, another organ whose visceral afferents are sharing the same dermatomal level will become hypersensitive at the same time. This development of a secondary visceral hyperalgesic state is simply a sign of further dysregulation of the dorsal horn and of sensory processing function at that level. While the understanding of the neuropathology of visceral pain syndromes such as IC is becoming crystallized, clinicians still struggle with the basic question of why some patients develop the problem of an upregulated dorsal horn and others do not. This is generally thought to be the interaction between the amount of noxious stimuli-both duration and severity, as well as the ability for the suprasacral influences, or down-ward modulating pathways, to control the biochemical changes occurring within the dorsal horn.  Diagnosis: The symptoms of IC, urgency and pain, tend to be cyclic and are the hallmarks of the disease. Bladder insult leads to epithelial layer damage and the resulting leakage of potassium into interstitium, followed by the activation of both parasympathetic sensory fibers (responsible for urgency) and C-fibers (fibers conducting nerve impulses) and the release of substance P (a polypeptide that transmits pain impulses). Pain symptoms of IC are:- Gyneurologic Symptoms: Dysparunia, Premenstrual flare, Flare after sex, Voiding symptoms, and Pain in the lower abdomen - vulva, urethra, vagina, medial thighs, perineum.

- Gynecologic Symptoms of Pelvic Pain: Dysparunia, Menstrual/premenstrual flare, Flares after sex, Pain in the lower abdomen and Dysmenorrhea.

Women with IC become accustomed to the urinary frequency and urgency, vaginal irritation, and chronic pelvic pain that typically accompany this condition. Identifying when a patient's flares occur can provide the key to the understanding cause, and therefore its successful treatment. If symptoms flare during or after sex, premenstrually, during allergy season, and/or in times of emotional and physical stress, then the likelihood of an IC diagnosis is substantially increased. The possibility that patient has IC should be considered in the following cases (4).- The patient has a diagnosis of recurrent UTI;

- A diagnosis of urethral syndrome has been given;

- There is a diagnosis of an overactive bladder, dry, with or without pain;

- There is a diagnosis of refractory endometriosis, vulvar vestibulitis, yeast vaginitis, or just pelvic pain.

- Physical examination -tender bladder and PUF questionnaire scare >8 and negative urinalysis.

PUF patient symptoms scale

Potassium Sensitivity Test (PST):The PST, also known as the KCL test or the Parsons test, involves instilling a potassium chloride solution into the bladder via urinary catheter. The Potassium Sensitivity Test is used primarily to diagnose IC, especially when the origin of symptoms is not clear. It measures epithelial permeability on outpatient basis and can be performed by any provider, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or primary care physician. Patients with a normal bladder typically do not absorb or react with pain/urgency to potassium chloride (KCL). However, potassium in most IC bladders stimulates the perivesical nerves and causes significant discomfort and inflammation in the bladder wall. The PST assesses a patient's response to the presence of potassium in the bladder. Majority of patients (>70%) with IC have positive PST and positive PST is not sufficient to conclusively diagnose IC. Procedure: Have patient void prior to testing. Prepare test and rescue solutions. Label syringes. Place drape under patient and prep area with Betadine swab. Insert catheter with sterile water/saline solution syringe attached. Slowly instill the 40 cc of sterile water/saline solution and leave catheter and syringe in place; wait for 5 minutes. Ask patient if solution provoked any change in urgency and/or discomfort and grade the change on a scale of 0 to 5. Draw off solution with the syringe and remove the syringe, leaving the catheter still in the bladder. Now attach KCL solution (40 mEq in bags of 100 mL)syringe to the catheter. Slowly instill the 40 cc of KCL solution and observe for patient reaction. If patient reacts - STOP!! The test is positive. Stop the instillation and grade the change of urgency and/or pain on a scale of 0 to 5 expressed by the patient. Drain off any instilled solution, flush with 60 ml of water, and remove syringe, leaving catheter in place. Instill rescue solution (Heparin 40,000 units + 8 cc 1% lidocaine hydrochloride + 3 cc 8.4% sodium bicarbonate; bring total volume of 20 cc with sterile water/saline solution) immediately with syringe. Remove catheter and syringe (together) from the bladder and ask patient to hold rescue solution for 15 to 20 minutes. Have patient void out rescue solution and test is completed. If patient does not react - Leave the catheter and syringe in place and wait 5 minutes. Now ask patient if KCL solution caused any change in urgency and/or pain and grade the change on the reporting sheet. If there is no difference noted between sterile water/saline solution and KCL solution after 5 minutes, leave KCL solution in the bladder and remove the catheter and patient drapes. Have patient void out solution. Grade any perceived discomfort after voiding and test is complete. PST Scoring:

Negative PST - no difference noted between solutions.

Positive PST - grading of 2 or more in KCL solution part of test for either urgency or pain. Difference noted between 2 solutions. Other optional tests that might be worthy of diagnostic consideration include the following:- Pelvic or transvaginal ultrasound

- Postvoid residual (PVR) urine volume evaluation

- Intravenous pyelogram to rule out presence of stones in the ureter. Abdominal pathology, or evaluation of the ureters, can be done via a computed tomographic scan. If voiding dysfunction is suspected, one might consider performing the Urodynamic evaluation.

- Cystoscopy: with hydrodistension under anesthesia is of great utility in helping to confirm a diagnosis of IC and is generally reserved for severe stage of the disease. Cystoscopy allows for a magnified inspection of the bladder and urethra to rule out any abnormalities, and enables biopsy (if needed). A small bladder capacity under anesthesia supports a diagnosis of IC and is inversely proportionate to the presence of Hunter's patch (5). In addition to is utility as a diagnostic tool, cystoscopy with hydrodistension has been shown to improve IC symptoms in 30% to 60% of patients within 2 to 4 weeks (after an initial period during which symptoms worsen), and is therefore used as an initial therapeutic option.

- Evolving tests: two promising clinical markers under investigation include GP51, a urinary glycoprotein normally found in the mucin lining of the urinary tract; and antiproliferative factor (APF). Patients with IC have lower levels of GP51 than control; further more, the lower levels appear to be unique to patients with IC. Antiproliferative factor (APF) inhibits proliferation of bladder epithelial cells and complex changes in epithelial growth factor levels (6).

Management:The key to successful treatment of IC is multimodal therapy. Patients with mild disease may do well with mono-drug therapy, whereas those multimodal approach to control all of their symptoms. These medications would be those that correct the epithelial dysfunction, neuro-modulating agents, or agents that control allergies.Symptom Control through Diet - In IC, foods that are high in potassium tend to provoke symptoms. The food stuffs mentioned most commonly in patients' complaints are citrus fruits, tomatoes, chocolate, and coffee, all of which are rich in potassium; authors recommend avoiding these foods for the patients with IC. As a practical measure, the foods mentioned are the primary ones recommended that IC patients avoid after beginning therapy.Bio-feed-back, Electric Stimulation and EMG - Some individuals with IC may benefit from bio-feed-back techniques such as urgency/frequency management techniques and methods of lowering resting pelvic floor muscular tone. Well-trained bio-feed-back personnel and careful patient selection are essential to the success of this mode of treatment. Peripheral cutaneous techniques or permanent implants, preceded test stimulation, can be used to affect neuromodulation for the treatment of IC in appropriate patients. Oral Regimen - Pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS; Elmiron) is the only drug of its kind approved to treat the pain of IC. Its mechanism of action appears to be to help restore to the mucus (GAG) of the bladder its normal function of regulating epithelial permeability. PPS may have additional effect, eg, it is known to inhibit mast cell activity. The authors recommend Pentosan polysulfate sodium 100 mg three times daily for use as first-line therapy for IC. Duration of use past 8 months shows response rate of 70% and higher. Furthermore, resistance to PPS has not been demonstrated in patients using this agent consistently for 3 years (7). Patients are recommended to stay on PPS therapy for at least 6 months; it is well tolerated with mild, infrequent, and transient side effects. In approximately 1% of patients mild liver function changes have been seen; these were not associated with jaundice or other clinical signs or symptoms. Patients often require the use of an agent to inhibit the neural hyperactivity-induced pain associated with IC. Amitriptyline (Elavil) and hydroxyzine (Atarax) are the two interventions most commonly administered for this purpose. Hydroxyzine (Atarax) exerts an antihistaminic effect and is therefore effective during allergic flares. Concomitant use of oxybutynin chloride (Ditropan XL) to reduce urgency and frequency is also recommended. Intravesical Treatments - It can be used alone in patients who are unable to tolerate oral treatment or those for whom oral treatment is ineffective. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solution is the first line and only agent approved by the FDA (1978) for bladder instillation. DMSO is an anti-inflammatory analgesic with muscle-relaxing properties that appears to increase the reflex firing of pelvic nerve efferent axons, increase bladder capacity, release nitric oxide from afferent neurons, and inhibit mast cell secretion. It is a safe and moderately effective first-line of therapy for patients with IC. DMSO has a good safety profile, although it leaves a garlic-like taste/odor on the breath and skin for up to 72 hours after treatment. Pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS) or Elmiron intravesical instillation - the PPS solution contain 200 mg (for women) or 400 mg (for men) mixed with 3 cc of 1% sodium bicarbonate and 8cc of 1% lidocaine instilled in the bladder and retained for 30 minutes and then voided. PPS instillation therapy offers a new option for IC patients who are unable to take PPS in its oral form. Other intravesical agents used are heparin, hyaluronic acid, Resiniferatoxin, and Bacillus Calmatte-Guerin. Exonerative Surgery - Cystectomy, complete with ureteroileal conduit or cystectomy, complete with continent diversion by any technique is done as a last resort. Promising Intravesical Treatment for Interstitial Cystitis: Intra-bladder administration of a solution containing lidocaine, bicarbonate, and heparin has shown to improve symptoms of IC and reduce dyspareunia (8). The results are encouraging and raise the possibility of an effective intravesical therapy that is well-tolerated and improves dyspareunia. Alkalization of 5% lidocaine by buffering with 8.4% sodium bicarbonate provides safe and reliable absorption into the bladder following intravesical administration. Heparin is widely used for intravesical therapy and effectively controls symptoms in approximately 50% of patients with painful bladder syndrome (PBS) / Interstitial Cystitis (IC). The efficacy of an intravesical therapeutic solution containing 40,000 IU of heparin, 8 mL of 2% lidocaine (160 mg), and 8.4% sodium bicarbonate was demonstrated in 35 patients with newly diagnosed IC and significant frequency, urgency, and pain. A single instillation produced immediate relief of symptoms of pain and urgency in 94% of the patients, which lasted for at least 4 hours in 50% of patients followed by telephone and as long as 14 to 24 hours in some. In 20 patients who received a further course for 2 weeks, relief of pain and urgency was sustained in 80% and lasted for at least 48 hours after the last intravesical treatment. The persistent relief of symptoms beyond the immediate anesthetic effect of lidocaine suggests that the solution may down-regulate bladder sensory nerves and accelerate recovery of the bladder (9). Interventional Therapy: cystoscopy with hydrodistention of the bladder performed under general anesthesia is believed to help 40% to 50% of patients with IC. Better results are seen in patients with a bladder capacity of 150 mL or greater before distention. A retrospective study compared 47 patients with IC who had undergone cystoscopy and hydrodistention and 37 patients with IC who had not. With the patient under general anesthesia, irrigation flowed under gravity (100-cm pressure) until it stopped, and hydrodistention was maintained for 2 minutes. Digital pressure was maintained against the urethra by the urologist to avoid leakage of the irrigant around the cystoscope. After the bladder was drained, the hydrodistention was repeated. Patients who underwent hydrodistention reported significantly more pain, vaginal pain, and dyspareunia or ejaculation pain than did those who did not have hydrodistention. Follow-up data for 43 of 47 patients who underwent cystoscopy and hydrodistention showed that 56% reported improvement, which was short-lived (mean duration of 2 month) in all but 1 patient who reported symptom relief lasting 24 months (10). | Multimodal Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome: |

|---|

| Treatment | Dosage | Indication |

|---|

Pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS) | 100 mg tid

200 mg bid | Treatment of pain related to IC/ PBS | Amitriptyline or

Other tricyclic

Antidepressant (TCA) | 25 mg qhs | Moderate/Severe anxiety; depression associated with chronic physical disease; neural pain modulation | Hydroxyzine and histamine | 25 mg qhs or

25 mg qam and qhs | Management of allergic conditions mediated reactions

Symptomatic relief of anxiety and tension

Behavioral interventions plus dietary changes

Intravesical therapies for acute exacerbations or control of symptoms |

Conclusion The prevalence of IC may be greater than has been previously believed. More accurate diagnosis has led to improvement in treatment outcomes and better patient selection for medical and behavior therapy. Since the disorders can co-exist, comprehensive evaluation and therapy are absolutely essential. The multi-drug oral regimen and intravesical instillation treatments described above are the modes of therapy used most often in the management of patients with IC. There is a need for continued efforts to educate providers about these conditions so they are sufficiently knowledgeable to diagnose and treat them. References:- Hanno PM, Landis JR, Mathews-Cook Y, et al. Lessons learned from the National Institutes of Health interstitial cystitis database. J Urol 1999;161(2):553-557.

- Theoharides TC. The mast cells: a neuro-immuno-endocrine master player. Int J Tissue React 1996;18(1):1-21.

- Butrick CW. Underlying Neuropathology of Interstitial Cystitis. The Female Patient May 2002 Supplement issue.

- Parsons CL, Dell J, Bullen M, et al. Increased prevalence of interstitial cystitis in urologic patients and gynecologic pelvic pain patients as determined using a new symptom questionnaire. J Urol 2002;167 (4 Suppl):65.

- Nigro DA, Wein AJ, Foy M, et al. Associations among cystoscopic and urodynamic findings for women enrolled in the Interstitial Cystitis Data Base (ICDB) Study. Urology 1997;49(5A Suppl):86-92.

- Byrne DS, Sedor JF, Estojak J, et al. The urinary glycoprotien GP51 as a clinical marker for interstitial cystitis. J Urol 1999;161(6):1786-1790.

- Nickel JC, Barkin J, Forrest J, et al. Randomized, double-blinded, dose-ranging study of Pentosan polysulfate sodium for interstitial cystitis [abstract]. J Urol 2001;165(5 Suppl):67.

- Welk BK, Teichman JM. Dyspareunia response in patients with interstitial cystitis with intravesical lidocaine, bicarbonate, and heparin. Urology 2008;71:67-70

- Parson CL. Successful down-regulation of bladder sensory nerves with combination of heparin and alkalinized lidocaine in patients with interstitial cystitis. Urology 2005;65:45-48

- Ottem DP, Teichman JM. What is the value of cystoscopy with hydrodistention for interstitial cystitis? Urology 2005;66:494-499

©

Women's Health and Education Center (WHEC)

|