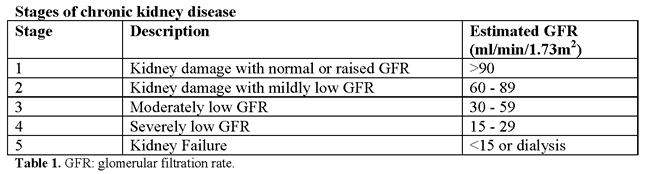

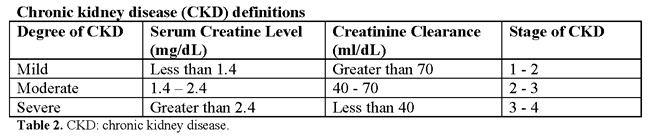

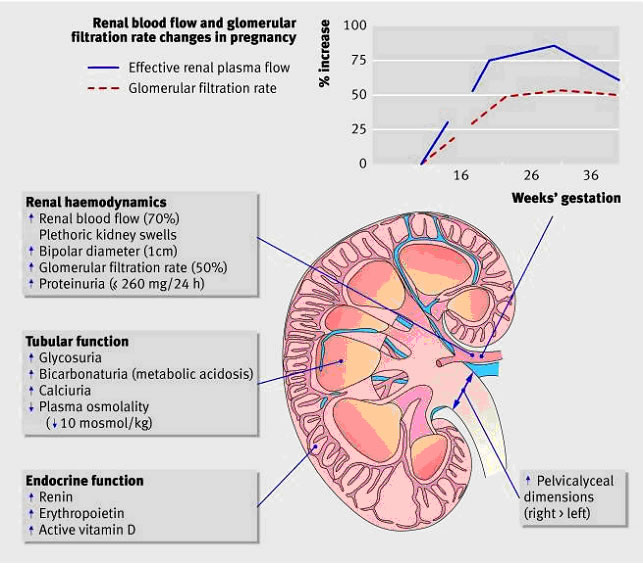

Хроническая болезнь почек и беременностьWHEC Практика бюллетень и клинической Управление медицинских работников.Образовательный грант предоставляется по охране здоровья женщин и образовательный центр (WHEC). Chronic kidney disease represents a heterogenous group of disorders characterized by alterations in the structure and function of the kidney. Its manifestations are largely dependent on the underlying cause and severity of the disease, but typically include decreased function, hypertension, and proteinuria, which can be severe. Etiologies are many, but examples of renal disorders common in young women include glomerular diseases (i.e. immunoglobulin A nephropathy, minimal change disease, and focal segmental glomerulonephritis), vascular diseases (i.e. thrombotic microangiopathies), tubulointerstitial diseases (i.e. nephrolithiasis and reflux nephropathy), and cystic diseases (i.e. polycystic kidney disease). Further, systemic diseases including diabetes, vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematous often involve the kidneys. Chronic kidney disease significantly increases the risk of adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes, and these risks increase with the severity of the underlying renal dysfunction, degree of proteinuria, as well as the frequent coexistence of hypertension. More frequent prenatal assessments by an expert multidisciplinary team are desirable for the care of this particularly vulnerable patient population. Obstetricians represent a critical component of this team responsible for managing each stage of pregnancy to optimize both maternal and neonatal outcomes, but collaboration with nephrology colleagues in combined clinics wherein both specialists can make joint management decisions is typically very helpful. Strategies for optimization of pregnancy outcomes include meticulous management of hypertension and proteinuria where possible and the initiation of preeclampsia prevention strategies, including aspirin. The purpose of this document is to discuss current management of pregnant patients with chronic kidney diseases, early diagnosis and postpartum management. Renal transplantation and pregnancy is also discussed. Avoidance of nephrotoxic and teratogenic medications is necessary, and renal dosing of commonly used medications must also be considered. The effect of pregnancy on kidney disease may manifest as a loss of renal function, particularly in the context of concomitant hypertension and proteinuria, and chronic kidney disease, even when mild, contributes to the high-risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including increased risks of preeclampsia, preterm delivery, and small-for-gestational age neonates. Incidence and BackgroundThe global prevalence of chronic kidney disease has been recently estimated to be approximately 13.4%, with a higher prevalence in women compared with men (1). Although the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in women of childbearing age seems relatively low, with estimates on the order of 0.1 – 4%, the implications of pregnancy in the context of chronic kidney disease are many and severe (2). Chronic kidney disease is now widely classified into five stages according to the level of renal function.  Stages 1 and 2 (normal or mild impairment with persistent albuminuria) affect up to 3% of women of child-bearing age (20-39 years). Stages 3-5 (glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min) affect around 1 in 150 women of child-bearing age (3). Because of reduced fertility and an increased rate of early miscarriage, pregnancy in these women is less common. Studies of chronic kidney disease in pregnancy have mostly classified women on the basis of serum creatinine values, but the review of literature suggest that around 1 in 750 pregnancies is complicated by stages 3-5. Some women are found to have chronic kidney disease for the first-time during pregnancy. Around 20% of women who develop early preeclampsia (<30 weeks' gestation), especially those with heavy proteinuria, have previously unrecognized chronic kidney disease.  Renal Anatomic Changes with PregnancyAnatomic changes include dilatation of the renal collecting system (calices, renal pelvis, and ureters), which peaks by 20 weeks of gestation (4). These changes occur as a result of the effect of progesterone, which reduces ureteral tone, peristalsis and contraction pressure even early in pregnancy, as well as mechanical compressive forces that occur as the ureters cross the pelvic brim as pregnancy progresses. Hydronephrosis is seen predominantly on the right side, attributed to the crossing of the right ureter over the iliac and ovarian vessels at an angle before entering the pelvis. In contrast, the left ureter travels at a less acute angle in parallel with the ovarian vein. Kidney length increases by approximately 1 – 1.5 cm, and kidney volume increases up to 30% (4). Therefore, the diagnosis of true obstruction can be difficult, and in women at risk (e.g. obstructive or reflux nephropathy), surveillance ultrasound scans can be helpful. Further, this dilatation is responsible for the increased risk of pyelonephritis after asymptomatic bacteriuria, and regular screening for urinary tract infection is recommended in at-risk patients (e.g. advanced chronic kidney disease, chronic immunosuppression) (2). Renal Physiologic Changes with PregnancyOwing to alterations in the hormones that govern vasodilation and vasoconstriction, several important hemodynamic changes also occur during pregnancy, most notably in systemic vascular resistance. This in turn leads to a decrease in mean arterial pressure, which typically begins in the first trimester with a nadir at 18-24 weeks of gestation, returning to baseline close to term. As such, women with mild hypertension may be able to discontinue medication in the early stages of pregnancy. In contrast, poorly controlled hypertension preconception and in early pregnancy portends a particularly poor prognosis (5).  Figure 1: Physiological changes to the kidney during healthy pregnancy Renal vasodilatation increases renal plasma flow, and hence the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Glomerular hyperfiltration is the most significant physiologic change associated with normal pregnancy, presenting clinically as a decrease in the serum creatinine level. An estimation of GFR is important in the diagnosis and management of kidney dysfunction during pregnancy. The inverse hyperbolic relationship between serum creatinine and GFR is blunted at the higher range of the GFR, which typifies pregnancy. In a study that measured GFR by proper clearance methodology in women with preeclampsia and in healthy gravid controls, a comparison of the serum creatinine level with the GFR revealed a profound depression in kidney function in women with preeclampsia that could not be easily appreciated by evaluation of the serum creatinine level (6). Modification in tubular function also occurs in normal pregnancies, with alterations seen in the tubular handling of glucose, amino acids, and uric acid. The most clinically relevant adaption is the alteration in protein excretion, wherein increased proteinuria is often attributed to hyperfiltration. Throughout pregnancy, the value for significant protein excretion is that which exceeds 300 mg in a 24-hour period (double the upper limit of normal in healthy adult). However, it should be highlighted that this upper limit has not been well-studied. One of the largest studies established 24-hour urinary excretion of total protein in 270 healthy pregnancies, reporting that mean 24-hour protein excretion was 116.9 mg with an upper 95th CI of 259.4 mg (6),(7). Because convincing evidence for significant glomerular leakage of protein in a normal pregnancy is insufficient, significant proteinuria should not necessarily be attributed to the hyperfiltration of pregnancy and requires assessment. Effects of Pregnancy on Kidney DiseaseOne of the most important considerations in the management of pregnancy in the context of chronic kidney disease is the potential for pregnancy to hasten disease progression and decrease the time to end-stage renal disease. Women with chronic kidney disease are less able to make the renal adaptations needed for a healthy pregnancy. Their inability to boost renal hormones often leads to normochromic normocytic anemia, reduced expansion of plasma volume, and vitamin D deficiency (8). Mild renal impairment (stages 1 – 2): Most women with chronic kidney disease who become pregnant have mild renal dysfunction and pregnancy does not usually affect renal prognosis. A case-control study of 360 women with primary glomerulonephritis and mild renal dysfunction (serum creatinine <110 μmol/l), minimal proteinuria (<1g/24h), and absent or well controlled hypertension before pregnancy showed that pregnancy has little or no adverse effect on long term (up to 25 years) renal function in the mother (9). Moderate to severe renal impairment (stages 3 – 5): Small mainly uncontrolled retrospective studies have shown that women with the worst renal function before pregnancy are at greatest risk of an accelerated decline in renal function during pregnancy. Preexisting proteinuria and hypertension both increase this risk (10). A prospective study assessing the rate of decline of maternal renal function during pregnancy in 49 women with chronic kidney disease stages 3-5 before pregnancy confirmed a decline in renal function during the third trimester, which persisted in most women and deteriorated to end stage renal failure (11). Women with both an estimated GFR <40 ml/min/1.73 m2 and proteinuria >1g/24 h before pregnancy showed an accelerated decline in renal function during pregnancy. Chronic hypertension predisposes women to preeclampsia – this may explain why some women with milder renal function dysfunction also have a gestational decline in renal function. The risk of such a decline is reduced when hypertension is controlled. Effects of Kidney Disease on PregnancyAs important as it is to consider the effect of pregnancy on the course of maternal chronic kidney disease, it is of equal importance to contemplate the effect of chronic kidney disease on pregnancy outcomes, because the degree of renal function impairment in addition to the presence of hypertension and proteinuria are also major determinants of poor maternal and perinatal outcomes. In women with renal insufficiency, the presence of GFR less than 40 mL/min/1.73 m2 and proteinuria with protein greater than 1 g/d before conception predicts poor maternal and fetal outcomes (11),(12). Outcomes examined included risk of cesarean delivery, preterm delivery at less than 34 weeks of gestation, small for gestational age (SGA), and need for neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission. The risk of adverse outcomes increased across stages of chronic kidney disease, with a general combined outcome (preterm delivery, NICU and SGA) of 21% compared with 80% for stage 1 compared with stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease, respectively. In those with advanced chronic kidney disease, significantly higher rates of cesarean delivery, preterm delivery at less than 37 or less than 34 weeks of gestation, as well as SGA less than the 10th and less than the 5th percentile have been described (13). Women with more advanced chronic kidney disease also are more likely to have higher rates of concomitant hypertension and proteinuria, which further increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. OPTIMIZATION STRATEGIESGiven the heightened risk for both adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in women with chronic kidney disease, in particular those with advanced disease, multidisciplinary care that includes nephrologists, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, neonatologists, and a specialized NICU is the ideal. Despite the inherent risks, several management strategies exist to optimize outcomes, beginning with preconception care through delivery and then extending into the postpartum period. These principles of management are summarized below: Hypertension Management

Proteinuria Management

Pregnancy is a prothrombotic state, and in patients with severe hypoalbuminemia, there is a significantly increased risk of venous thromboembolic disease (16). No specific guidelines exist for the management of anticoagulation during pregnancy among those with chronic kidney disease and significant proteinuria, but expert opinion suggests that women with severe proteinuria and a serum albumin level of less than 2.0 – 2.5 g/dL should receive thromboprophylaxis throughout pregnancy and continued for at least 6 weeks postpartum (17). Anticoagulation also should be considered among those with lesser degrees of proteinuria with additional risk factors, including prolonged periods of immobility, obesity, or kidney diseases with higher risks of thrombosis (e.g. membranous nephropathy and vasculitis). The safety of sub-cutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin is well established for use in pregnancy. Preeclampsia Prevention

Calcium and vitamin D supplementation also have been evaluated as preventive strategies for preeclampsia. A systematic review included randomized controlled trials comparing high-dose (at least 1 g daily of calcium) or low-dose calcium supplementation during pregnancy with placebo or no calcium in the prevention of preeclampsia (19). The assessment of high-dose calcium greater than 1 g/d included 13 studies and 15,370 women, noting that the risk of hypertension was reduced with calcium supplementation compared with placebo, along with significant reduction in the risk of preeclampsia. More recently, the benefit of vitamin D and calcium supplementation in pregnancy of risk reduction of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension was assessed by a meta-analysis of 27 randomized controlled trials including approximately 28,000 women noting that calcium, vitamin D, and calcium plus vitamin D could lower the risk of preeclampsia when compared with placebo (20). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends daily supplementation with 1.5 - 2 g of oral elemental calcium in populations with low dietary intake for prevention of preeclampsia, but vitamin D supplementation requires further study. Other Neurological and Obstetrical Management Magnesium, a frequently used medication for eclampsia prevention or fetal neuroprotection, is cleared by the kidneys, and as such, magnesium toxicity presents a significant risk in women with advanced chronic kidney disease, especially those on dialysis. Thus, regular assessment of serum magnesium concentrations and deep tendon reflexes and a lower constant infusion rate (e.g. 1 g/h) are often indicated. Maternal anemia is common in women with chronic kidney disease, and early institution of oral iron, intravenous iron sucrose, or both in addition to erythropoietin-stimulating agents when pregnancy is recommended. Hypocalcemia and hyperphosphatemia due to secondary hyperparathyroidism from advanced chronic kidney disease can be treated safely with oral calcium carbonate supplementation, binders, or both as well as vitamin D analogues. Maternal acidosis will result in progressive fetal acidemia, and as such, maternal serum pH ideally should be maintained at greater than 7.2. This may require initiation of sodium bicarbonate therapy, and in extreme cases, is an indication for dialysis. Women with chronic kidney disease also may have electrolyte abnormalities, and dietary counseling for a low-potassium diet should be initiated first, but binding resins can be used if needed. Again, this may be an indication to initiate dialysis.

Owing to increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, more frequent prenatal assessments to allow for close maternal and fetal monitoring may be necessary. A significantly rapid and severe decline in renal function is an indication for preterm delivery or termination of pregnancy. Antepartum fetal surveillance should be conducted according to the guidelines (21). Review Antepartum Fetal Surveillance http://www.womenshealthsection.com/content/obs/obs005.php3 In the absence of maternal or fetal compromise, consideration should be given to delivery at or near term, with cesarean delivery for usual obstetric indications. END-STAGE RENAL DISEASE (ESRD)In the population of women with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on dialysis, conception and maintenance of pregnancy were historically infrequent and complex events. Fertility rates are typically low in those on hemodialysis and even lower in women on peritoneal dialysis, thought to be due impaired pituitary release of luteinizing hormone contributing to anovulation (22). To date, the highest documented pregnancy incidence is 15.6% in eligible intensively dialyzed home dialysis patients who conceived between 2001 and 2006, and outcomes also have improved, with live birth rates exceeding 80% in centers using intensified dialysis regimens (23). There is positive relationship between number of hours on dialysis and improved outcomes, with a decreased risk of preterm delivery before 37 weeks of gestation and small-for-gestational-age neonates less than the 10th percentile (24). In those with ESRD and no residual renal function, current recommendations a minimum of 36 h/week, but in women with residual renal function, this intensified therapy may not be required, and the dialysis prescription should be personalized to meet specific needs. Compared with normal women, pregnancies in uremic patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis have a higher risk of adverse outcomes in mother and fetus, such as, spontaneous abortion, hypertension, preeclampsia, polyhydramnios, preterm labor, and premature birth (25). Since the first case of pregnancy and successful delivery of patients on hemodialysis in 1970s, with the continuous development and improvement of dialysis technologies and experiences, more and more successful cases have been reported. During the past years before pregnancy, the dialysis scheme of the uremic patients is usually 4-hour dialysis sessions 3 times weekly. During pregnancy intensive dialysis and multidisciplinary cooperation according to the recommendations in the available literatures on pregnant women is summarized below. Firstly, the total weekly hemodialysis is increased from 12 to 20 hours weekly, the dialyzer with high efficiency biocompatible membrane is used, the average blood flow is maintained from 180 to 240 mL/min and the dialysate flow at 500 mL/min. Low-molecular weight-heparin (bolus dose of 1000 IU followed by 250 IU every hour) is used to minimize the hemorrhagic risk and avoid coagulation of the dialyzer (26). Secondly, control of dry weight by slow continuous ultrafiltration in order to achieve the goal of 0.5 kg on weight gain per week is maintained. Thirdly, in order to target the postdialysis blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg and to avoid intradialytic hypotension (<120/70 mm Hg), the dialyzed pregnant women are treated by combination of ultrafiltration assessments and antihypertensive drugs, including long-acting calcium antagonist and alpha-methyldopa. Fourthly, management of anemia. The patients are recommended to receive subcutaneous recombinant human erythropoietin at a dose of 10,000 IU twice per week and intravenous iron administration of iron-sucrose at a dose of 100 mg biweekly, as well as 10 mg of folic acid supplementation. In addition, nutritional support is also recommended for the pregnant women as follows: protein intake of 1 g/kg/d and 20 g/d more, calorie intake of 35 to 40 kcal/d. The dose of intake for calcitriol and calcium carbonate D3 is 0.25 μg/d and 0.6 g/d, respectively. With regard to the obstetric care, after the pregnancy is confirmed by pelvic ultrasound, the fetal biometries are assessed according to the guidelines. The single umbilical artery, polyhydramnios and fetal growth restriction and ultrasound for fetal anomalies needs to be followed. Clearance of urea plays a crucial role in pregnancy success, and there exists correlation between blood urea levels and gestational age, with urea levels lower than 48 mg/dL being associated with a gestational age of at-least 32 weeks (27). In the absence of evidence of maternal or fetal compromise, induction of labor is considered at term (37-39 weeks of gestation) to avoid spontaneous labor in an anticoagulated woman. Delivery should take place in a center with resource necessary to care for complex maternal and fetal situations. Initiation of magnesium sulfate for prevention of preeclampsia or fetal neuroprotection in cases of preterm delivery must be prescribed with vigilance. Postpartum, breastfeeding is safe in women undergoing dialysis. Most medications that are compatible with pregnancy are also safe while breastfeeding, but providers also should be attentive to avoid over-aggressive ultrafiltration and dehydration, which might impede breast milk supply. RENAL TRANSPLANTATIONEstimates indicate that the proportion of women with renal transplants who become pregnant is approximately 2% – 5% (28). Pregnancy rates are significantly lower than in the age-matched general population, and it is not clear whether this represents decreased fertility or counseling practices and patient choice (29). At this time, much of the information available to guide practice comes from single-center experiences and systematic reviews and through transplant registries. The recently published Transplantation Pregnancy Registry International 2015 Annual Report includes 1,892 pregnancies in kidney recipients and 109 in kidney-pancreas recipients and is the largest of the available registries providing data on both maternal and fetal outcomes (30). After kidney transplantation as in all chronic kidney disease stages, the degree of kidney impairment, hypertension and proteinuria are acknowledged factors in the pathogenesis of adverse pregnancy-related outcomes, even though their pathogenesis in incompletely understood. The clinical choices in cases at high risk of malformations or kidney function impairment (pregnancies under mycophenolic acid or with severe kidney-function impairment) require merging clinical and ethical approaches in which, beside the mother and child dyad, the grafted kidney is crucial "third element." Bioethical aspects (31):

Which patients are the "best candidates" for pregnancy after kidney transplantation and which patients are not:

The Study Group therefore proposes an individualized evaluation in all the cases. A pregnant grafted woman has been defined as a complex chimera with at least three cell populations: her own one, the donor organ and the fetus. Previous pregnancies and blood transfusions may have added other cell populations. The tolerance system is complex and not all antigens induce a response; tolerance may be the result of exposure of particular antigens or complexes (32). Pregnancy outcomes after renal transplantation are generally thought to be superior to those in women undergoing dialysis. Pregnancy complications occurs more commonly in renal transplant recipients as compared with the general population, including hypertension (54% vs 5%), preeclampsia (27% vs 3.8%), and gestational diabetes (8% vs 3.9%). Additional adverse outcomes include low birth weight, increased risk of cesarean delivery, and admission to NICU (33). Pregnancy in the third post-transplant year was not associated with an increased risk of graft loss. On the other hand, live birth rates tend to be higher in the first 2 years post-transplantation. A meta-analysis of outcomes of 4,700 pregnancies in renal transplant recipients indicated a higher live birth rate (80%) with a mean interval transplant and pregnancy of less than 2 years compared with intervals of 2-3 years, 3-4 years and more than 4 years (live birth rates 64%, 76%, and 75%, respectively) (34). However, for those conceiving less than 2 years post-transplant, higher risks of other adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, cesarean delivery, and preterm birth are reported. The American Society of Transplantation Guidelines provides some direction and recommends avoidance of conception in the first year of transplantation (35). Pregnancy is deemed safe if there has been no rejection within the past year, adequate and stable graft function as evidenced by serum creatinine levels less than 1.5 mg/dL, no or minimal proteinuria, no acute infections that may affect fetal growth and well-being, and stable maintenance immunosuppression with pregnancy safe medications. Cesarean Delivery: In patients undergoing cesarean delivery, the obstetrician must be attentive to the location of the transplanted kidney and ureter by reviewing operative summaries as well as ultrasonographic imaging before delivery. Often the ureter is reimplanted at the dome of bladder, and thus a common recommendation is to avoid creation and development of a bladder flap at the time of cesarean delivery. POSTPARTUM CAREIt can take up to 3 months, occasionally longer, for the physiological changes of pregnancy to disappear. During that time, close monitoring of fluid balance, renal function, blood pressure, and a further review of drug treatment are necessary. Women who have new onset proteinuria associated with preeclampsia should be followed until proteinuria disappears, or until a diagnosis of renal disease is made. Breastfeeding should be encouraged in women with chronic kidney disease. Information is confusing as to the extent to which some immunosuppressive drugs – such as ciclosporin and tacrolimus – appear in breast milk (36). But prednisolone, azathioprine, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are barely detectable in breast milk. It is still unclear whether the benefits of breastfeeding are countered by neonatal absorption of immunosuppressive drugs. Most experts encourage mothers who want to breastfeed but are taking immunosuppressive drugs to do so as long as the baby is thriving. SummaryChronic kidney disease with pregnancy represents a unique and complex situation with increased risks of adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. Women with mild renal dysfunction (stages 1 – 2) usually have an uneventful pregnancy and good renal outcome. Clinical features, in particular uncontrolled hypertension, heavy proteinuria (>1 g/24h), and recurrent urinary tract infections have an independent and cumulative negative effect on pregnancy. Women with moderate to severe disease (stages 3 – 5) are at highest risk of complications during pregnancy and of an accelerated decline in renal function. Successful management of women with chronic kidney disease during pregnancy requires teamwork between primary care clinicians, midwives, specialists, and the patient. Frequent monitoring of simple clinical and biochemical features will guide timely expert intervention to achieve optimal pregnancy outcome and conservation of maternal renal function. Pregnancy is an added value for women with kidney transplantation; fertility is at least partly restored, and a successful pregnancy is possible, frequent, and usually successful. However, kidney transplantation pregnancies have a higher risk of thromboembolism, preterm delivery and small for gestational age babies than pregnancies in the general population. The side effect of this positive outlook is that evidence is heterogenous and sometimes difficult to interpret. This lack of certitudes should be borne in mind at counseling, and strongly supports shared choices in the context of multidisciplinary care, as well as individualized approaches. References

|