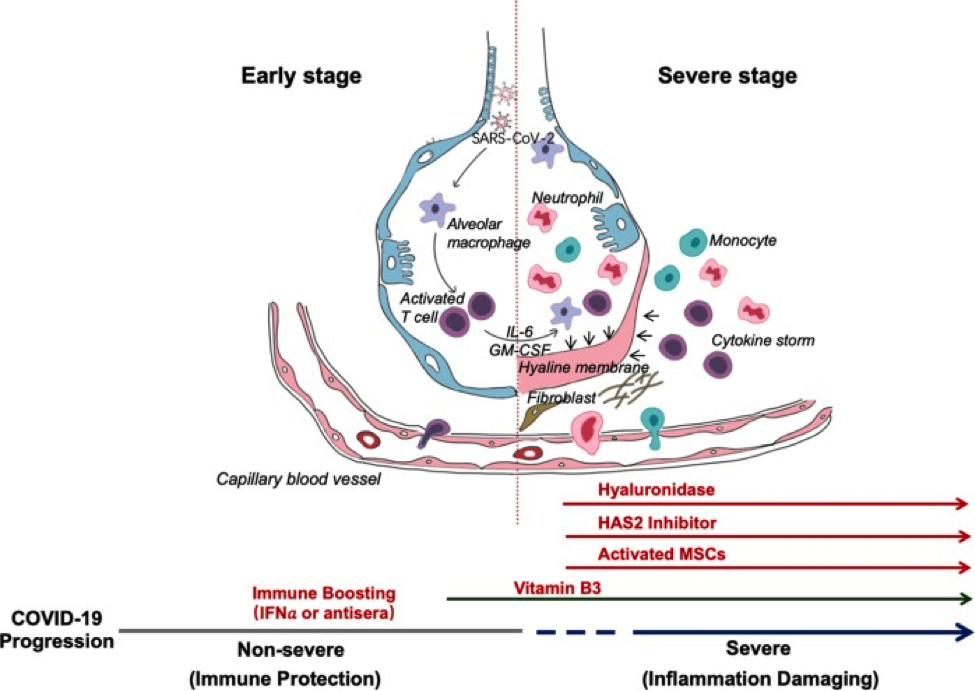

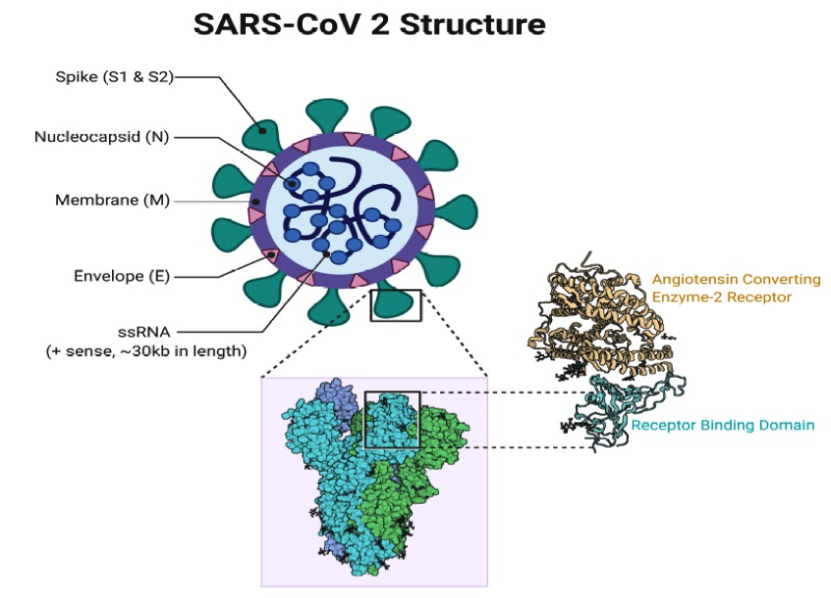

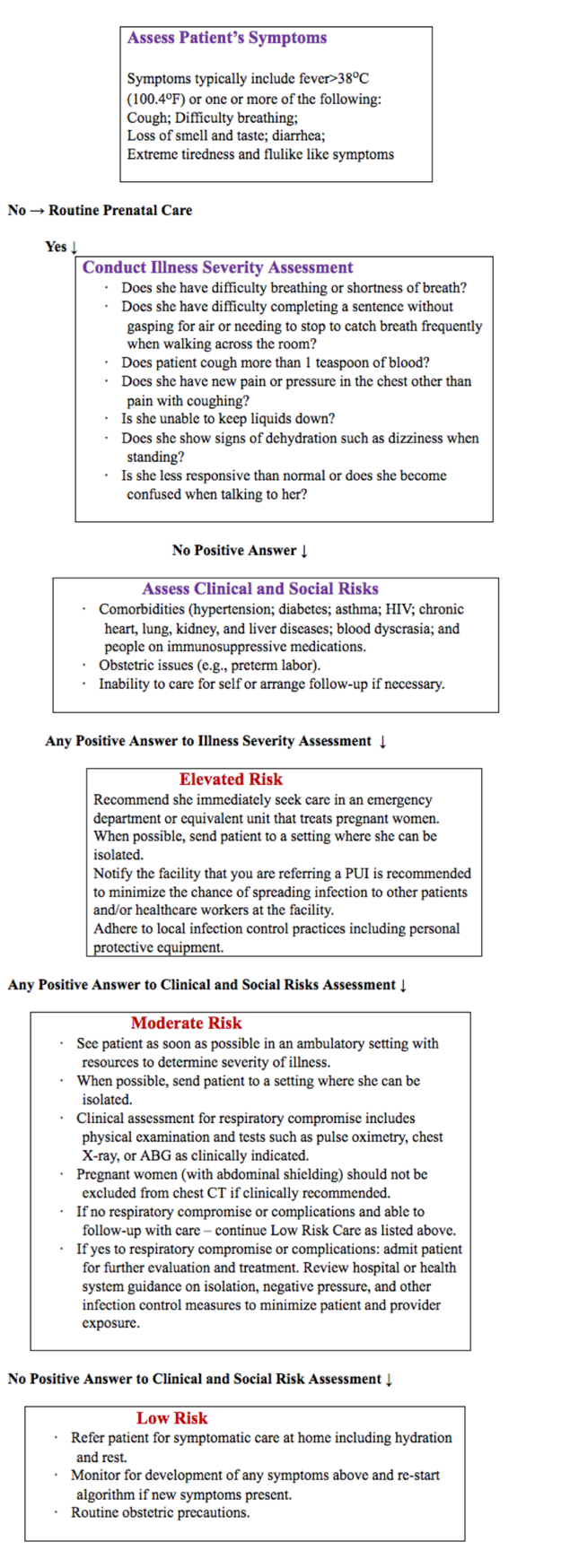

Новый коронавирус (COVID-19) Болезнь и беременностьБюллетень WHEC Практика и клинической управления для медицинских работников. Образовательный грант предоставляемых Здоровье женщин и центр образования (WHEC). Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) is an emerging, rapidly evolving situation. The entire world is at war with an invisible enemy – the novel coronavirus. COVID-19 and the disease it causes, have triggered unprecedented turmoil and disruption around the world. The Women's Health and Education Center's (WHEC's) publications in collaboration with the United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organization (WHO) will provide updated information as it becomes available. It was first detected in China in 2019, as an outbreak of respiratory disease caused by a novel (new) coronavirus. It has now been detected in more than 150 countries, including United States (U.S.). As of 1 May 2020, in U.S. more than 1 million people have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and more than 60,000 have died from the disease. Worldwide to date more than 3 million people have been diagnosed and more than 200,00 deaths from COVID-19 has been reported. The virus has been named "SARS-CoV-2" by the WHO, and the disease it causes has been named "coronavirus disease 2019" (abbreviated "COVID-19"). In U.S., different parts of the country are seeing different levels of COVID-19 activity. The U.S. is in the acceleration phase of the pandemic. The WHO and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)) have released Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and guidance for Evaluating and Testing Persons for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). The purpose of this document is to aid clinicians providing care during the rapidly evolving COVID-19 pandemic. As the situation evolves, this document may be updated or supplemented to incorporate new data and relevant information. COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for the healthcare providers is also included in this review. BackgroundScientists and clinicians have learned much of COVID-19 and its pathogenesis (1): not all people exposed to COVID-19 are infected, and not all infected patients develop severe illness. Many are asymptomatic. Accordingly, COVID-19 infection can be divided into three stages (2): Stage I: an asymptomatic incubation period with or without detectable virus; From the point of view of prevention, individuals at stage I, the stealth carriers, are the least manageable because, at least on some occasions, they spread the virus unknowingly: indeed, the first asymptomatic transmission has been reported in Germany (3). The role of asymptomatic COVID-19 infected individuals in disseminating the infection remains to be defined. Among over 1,000 patients analyzed in Wuhan (China), except occasionally in children and adolescence, it infects all the other age groups evenly. About 15% of the confirmed cases progress into the severe phase, although there is a higher chance for patients over 65 to progress into the severe phase (1). One of the biggest unanswered question is why some people develop severe disease, whilst others do not. Clearly, the conventional wisdom based on overall immunity of the infected patients cannot explain this broad spectrum in disease presentation. After an incubation period, the invading COVID-19 virus causes non-severe symptoms and elicits protective immune responses. The successful elimination of the infection relies on the health status and HLA haplotype of the infected individual. In this period, strategies to boost immune response can be applied. If the general health status and the HLA haplotype of the infected individual do not eliminate the virus, the patient then enters the severe stage, when strong damaging inflammatory response occurs, especially in the lungs. At this stage, inhibition of hyaluronan (HA) synthase and elimination of hyaluronan can be prescribed. Cytokine activated mesenchymal stem cells can be used to block inflammation and promote tissue reparation. Vitamin B3 can be given to patients starting to have lung CT image abnormalities. Two-phase immune responses are induced by COVID-19 infection. The innate response to tissue damage caused by the virus could lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), in which respiratory failure is characterized by the rapid onset of widespread inflammation in the lungs and subsequent fatalities (4). The symptoms of ARDS patients include short/rapid breathing, and cyanosis. Severe patients admitted to Intensive care units (ICUs) often require mechanical ventilators and those unable to breath have to be connected to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) to support life (5). CT images revealed that there are characteristic white patches called "ground glass" contained fluid in the lungs (6). Recent autopsies have confirmed that the lungs are filled with clear liquid jelly, much resembling the lungs of wet drowning. Although the nature of the clear jelly has yet to be determined, HA is associated with ARDS; moreover, during SARS infection, the production and regulation of HA is defective. Pneumonia arising from any infectious etiology is an important cause of morbidity and mortality among pregnant women. It is most prevalent non-obstetric infectious condition that occurs during pregnancy (7). In one study pneumonia was the 3rd most common cause of indirect maternal death (8). Approximately 25% of pregnant women who develop pneumonia will need to be hospitalized in critical care units and require ventilatory support. Although bacterial pneumonia is a serious disease when it occurs in pregnant women, even when the agent(s) are susceptible to antibiotics, viral pneumonia has even higher levels of morbidity and mortality during pregnancy. As with other infectious diseases, the normal maternal physiologic changes that accompany pregnancy – including altered cell-mediated immunity and changes in pulmonary function – have been hypothesized to affect both susceptibility to and clinical severity of pneumonia (9). This has been evident historically during epidemics. The case fatality rate for pregnant women infected with influenza during the 1918 - 1919 pandemic was 27% - even higher when exposure occurred during the 3rd trimester and upwards of 50% if pneumonia supervened. During the 1957-1958 Asian flu epidemic, 10% of all deaths occurred in pregnant women, and their case fatality rate was twice as high as that of infected women who were not pregnant. The most common adverse obstetrical outcomes associated with maternal pneumonias from all causes include premature rupture of membrane (PROM) and preterm labor, intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and neonatal death (10). Historically, pregnant individuals have been thought to be at increased risk of severe morbidity from specific respiratory infections. With regard to COVID-19, the limited data currently available do not indicated that pregnant individuals are at an increased risk of infection or severe morbidity (e.g. need for ICU admission or mortality) compared with nonpregnant individuals in the general population. Pregnant patients with comorbidities may be at increased risk for severe illness consistent with the general population with similar comorbidities. To date, consistent with our experience with other respiratory viruses such as MERS, SARS, and influenza, there is no evidence of vertical transmission of COVID-19. WHEC will continue to diligently monitor the literature for any COVID-19 risk signals in pregnancy. Initially, the new virus was called 2019-nCoV. Subsequently, the task of experts of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) termed it the SARS-CoV-2 virus as it is remarkably similar to the one that caused the SARS outbreak (SARS-CoVs). On February 11, 2020 the WHO, announced that the disease caused by this new CoV was a "COVID-19", which is the acronym of "coronavirus disease 2019." The COVID-19 has become the major pathogens of emerging respiratory disease outbreaks. They are a large family of single-stranded RNA viruses (+ssRNA) that can be isolated in different animal species. For reasons yet to be explained, these viruses can cross species barriers and can cause in humans, illness ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as acute respiratory distress syndrome and pneumonia. COVID-19 are positive-stranded RNA viruses with a crown-like appearance under an electron microscope (coronum is the Latin term for crown) due to the presence of spike glycoproteins on the envelope. In general, estimates suggest that 2% of the population are healthy carriers of COVID-19 and that these viruses are responsible for about 5% to 10% of acute respiratory infections (11). The possibility of transmission before symptoms that individuals who remain asymptomatic could transmit the virus. It is concluded virus is transmitted from human-to-human, and symptomatic people are the most frequent source of COVID-19 spread. As with other respiratory pathogens, including flu and rhinovirus, the transmission is believed to occur through respiratory droplets from coughing and sneezing. Aerosol transmission is also possible in case of protracted exposure to elevated aerosol concentrations in closed spaces. Based on data from the first cases in Wuhan and investigations conducted by the China CDC and US CDCs, the incubation time could generally be within 3 to 7 days, and up to 2 weeks as the longest time from infection to symptoms was 12.5 days (12). This data also showed that this novel epidemic doubled about every 7 days, whereas the basic reproduction number (R0 - R naught) is 2.2. In other words, on average, each patient transmits the infection to an additional 2.2 individuals. Of note, estimation of the R0 of the SARS-CoV epidemic in 2002-2003 were approximately 3 (13). Further studies are needed to understand the mechanisms of transmission, the incubation times, possibility of transplacental transmission and the clinical course, and the duration of infectivity. The paucity of evidence challenges some of the key decisions that need to be addressed. For example, one question that has arisen is whether pregnant healthcare workers should receive special consideration. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, in which pregnant women were more likely to develop complications than nonpregnant women, the CDC recommended that pregnant women should strictly adhere to the same measures that were recommended for all healthcare personnel, although certain work accommodations, such as avoidance of aerosol-generating procedures on infected patients, could be offered as an option. In contrast, the CDC recommended that pregnant healthcare workers not care for patients with Ebola virus disease, given severity of illness in mothers and their neonates, the high-risk of transmission, and the challenges related to the required PPE for Ebola care. Whether special accommodations should be made for COVID-19 require data on the severity of COVID-19 in pregnant women (17). This algorithm is designed to aid practitioners in promptly evaluating and treating pregnant women with known exposure and/or those with symptoms consistent with COVID-19 (persons under investigation [PUI]): All individuals, including pregnant individuals, are encouraged to take precautions to avoid exposure to COVID-19 as the pandemic evolves. We understand that many pregnant individuals are experiencing increased stress and anxiety due to COVID-19. When counseling pregnant individuals about COVID-19, it is important to acknowledge that these are unsettling times. Healthcare providers should be vigilant in screening including pregnant patients. This can be done via phone or tele-health before a visit to allow facilities to appropriately prepare and optimize care coordination needs. Of note, healthcare professional should follow their healthcare facility's policies and their local and state health department policies for notification of a person under investigation for COVID-19. Community mitigation efforts to control the spread of COVID-19 have been implemented across the United States. Although these efforts are important, healthcare professionals should be aware of the unintended effect they may have, including limiting access to routine prenatal care. Obstetricians and gynecologists should continue to provide medically necessary prenatal care, referrals, and consultations, although modifications to healthcare delivery approaches may be necessary. Obstetricians and gynecologists also should consider creating plan to address the possibility of a decreased healthcare workforce, potential shortage of personal protective equipment, and limited isolation rooms, and should maximize the use of telehealth across as many aspects of prenatal care as possible. Addressing inequalities in racial and ethnic minority populations: Healthcare professionals can work toward addressing inequalities in the healthcare system by confronting individual and structural biases. Emerging data indicate disproportionate rates of COVID-19 infection, severe morbidity, and mortality in some communities of color, particularly among Black, Latinx, and Native American people. Social determinants of health, current and historic inequalities in access to healthcare and other resources, and structural racism contribute to these disparate outcomes. These inequalities also contribute to disproportionate rates of comorbidities in these communities that place individuals at higher risk of severe illness from COVID-19. Access to COVID-19 testing and healthcare resources for those testing positive or who would be considered as persons under investigation also may be limited in these communities. This information is intended to aid hospitals and clinicians in applying broader CDC interim guidance on infection control (14): The many benefits of mother/infant skin-to-skin contact are well understood for mother-infant bonding, increased likelihood of breastfeeding, stabilization of glucose levels, and maintaining infant body temperature. Transmission of COVID-19 after birth via contact with infectious respiratory secretions is a concern, the risk of transmission and clinical severity of COVID-19 in infants is not clear. Considerations in this decision include: If separation is not undertaken, other measures to reduce the risk of transmission from mother to infant could include the following, again, utilizing shared decision-making: *Hand hygiene includes use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer that contains 60% to 95% alcohol before and after all patient contact, contact with potentially infectious material, and before putting on and upon removal of personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves. Hand hygiene can also be performed by washing with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. If hands are visibly soiled, use soap and water before returning to alcohol-based hand sanitizer. If the decision is made to temporarily put the mother with known or suspected COVID-19 and her infant to reduce the risk of transmission in separate rooms, the following should be considered (16): Key Highlights of the Recommendations: Pregnant women admitted with suspected COVID-19 or who develop symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 during admission should be prioritized for testing. Because of potential for asymptomatic patients presenting to labor and delivery units, particularly in high prevalence areas, additional testing strategies may be appropriate. For initial diagnostic testing for COVID-19, CDC recommends collecting and testing upper respiratory tract specimen (nasopharyngeal swab). CDC also recommends testing lower respiratory tract specimens, if available. For patients who develop a productive cough, sputum should be collected and tested for COVID-19. The induction of sputum is not recommended. For patients for whom it is clinically indicated (e.g., those receiving invasive mechanical ventilation), a lower respiratory tract aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage sample should be collected and tested as a lower respiratory tract specimen. Specimens should be collected as soon as possible once a PUI is identified, regardless of the time of symptom onset. Laboratory findings: include lymphopenia, prolonged prothrombin time (PPT), and elevated lactate dehydrogenase; radiology findings include bilateral patchy shadows or ground-glass opacity of the lungs on chest computed tomography (CT) (17). Diagnostic testing using real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction has moved from CDC to include state public health laboratories, and most recently, commercial laboratory options and work to develop a serology test for COVID-19 has begun. Three case series, for a total of 31 pregnancies affected by COVID-19, have been published (18), and a WHO report from China provides limited information on 147 pregnancies (19). Reviews examining features during pregnancy of diseases caused by other coronaviruses (e.g., SARS, and Middle East respiratory syndrome [MERS]), in the context of limited information on COVID-19 during pregnancy, have been published. Guidelines for pregnant women have been included in this review and the responses to frequently asked questions about COVID-19 and pregnancy have been posted by the WHO. Based on the available information, pregnant people seem to have the same risk of getting COVID-19 infection as adults who are not pregnant. However, we do know that: Pregnant people should protect themselves from COVID-19 by: Risks to the pregnancy and to the baby: How to protect yourself: Mother-to-child Transmission Maternal Morbidity and Mortality due to COVID-19 One critical question about COVID-19 relates to the case-fatality rate of the disease. Early data from Wuhan, China suggested that 4.3% of 138 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 died (2). However, it was recognized that early estimates can overestimate the case-fatality rate because mild or asymptomatic cases are often missed early in the outbreak. Later data from the Chinese CDC based on more than 70,000 cases suggested a lower case-fatality rate of 2.3% (20). Recent data reported in the media from Iran have suggested a higher case-fatality rate of just less than 9% (21). South Korea has reported 75 deaths among 8,236 confirmed cases for a lower case-fatality rate of 0.9% (22). The case-fatality rate depends not only on the disease and complete ascertainment of cases, but on the health care provided to affected patients and the age and health of the population studied. Given the small number of cases in the U.S. and the limited testing performed thus far, the case-fatality rate for persons cared for in the U.S. is unknown. Preliminary information suggests that pregnant women are not more severely affected than the general population. However, the numbers of pregnant women reported have been small, and comparison is needed with non-pregnant women of similar age rather than with all persons with COVID-19, a population that is older (median age is approximately 50 years) and has underlying conditions. Whether intrauterine or perinatal transmission occurs is also unknown. Among the small number of pregnancies in U.S., reported thus far, no evidence of transmission to the neonate has been observed. However, these women were nearly all infected in the third trimester and most underwent cesarean delivery (23). The effects of the virus earlier in pregnancy are completely unknown; no neonates have been delivered to women infected in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy. Prenatal Care and Mode of Delivery Current recommendations are well supported, based largely on what we know from seasonal influenza: patients should avoid contact with ill persons, avoid touching their face, cover coughs and sneezes, wash hands frequently, disinfect contaminated surfaces, and stay home when sick (24). Prenatal clinic should ensure all pregnant women and their visitors are screened for fever and respiratory symptoms, and symptomatic women should be isolated from well women and required to wear a mask (24). The mode of birth should be individualized and based on a woman's preferences alongside obstetric indications. Cesarean sections should only be performed when medically justified. Breastfeeding If you have COVID-19: patient along with the family and healthcare providers, should decide whether and how to start or continue breastfeeding. Breast-milk provides protection against many illnesses and is the best source of nutrition for most infants. In limited studies COVID-19 has not been detected in breast milk. However, we do not know for sure whether mothers with COVID-19 can spread the virus via breast milk. Testing Newborns If available, testing well newborns will facilitate plans for care after hospital discharge; will determine the need for ongoing precautions and use of PPE among hospitalized infants; and will contribute to our understanding of viral transmission and newborn illness (25). If baby cannot be tested, then treat the baby as if virus-positive for the 14-day period of observation. Mother should still maintain precautions until she meets the criteria for non-infectivity as above (26). Persons with COVID-19 who have symptoms and were directed to care for themselves at home may discontinue isolation under following conditions: Possible strategy to discontinue home isolation for immunocompromised persons with COVID-19, when a test-based strategy is feasible and desired: Therapeutic Options There are no drugs or other therapeutics approved by the U.S. FDA to prevent or treat COVID-19. Use of investigational therapies should ideally be done in the context of enrollment in randomized controlled trials. These medications are not recommended in pregnancy. Clinical trials are available @: ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=COVID-19 No country can beat this alone. Global solidarity is essential for the elimination of COVID-19 pandemic. If the virus persists in one community, it remains a threat to all communities, so discriminatory practices place us all at risk. Member States have a responsibility to ensure that everyone is protected from this virus and its impact. This may require special measures and protection for particular groups most at risk or disproportionately impacted. To best respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, UN Secretary-General António Guterres calls on world leaders to come together and offer an urgent and coordinated response to this global crisis. The three-part action plan includes: In this un precedented situation the normal rules no longer apply, and the magnitude of the response must match it scale. The world faces a common enemy. We are at war with a virus. The focus is rightly on saving lives, for which universal access to healthcare is imperative. Six key human rights messages (27): Strengthening international cooperation and take steps towards the provision of universal health care, collaborating in developing a vaccine and treatment for pandemic is of utmost importance. Expediting trade and transfer of essential medical supplies and equipment, including PPE for healthcare and other front-line workers, and addressing intellectual property issues, to ensure that COVID-19 treatments are available and affordable to all. Take the lessons learned from this pandemic to refocus action on ending poverty and inequalities and addressing the underlying human rights concerns that have left us vulnerable to the pandemic and greatly exacerbated its effects with a view to building a more inclusive and sustainable world including for future generations. The availability of a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19 is well-recognized as an additional tool to contribute to the control the pandemic. At the same time, the challenges and efforts needed to rapidly develop, evaluate and produce this at scale are enormous. It is vital that we evaluate as many vaccines as possible as we cannot predict how many will turn out to be viable. Highlights of WHO actions so far (28): WHO expert groups are also considering (28): COVID-19 is the latest in a series of diseases caused by emerging pathogens in the past two decades, from SARS to 2009 H1N1 influenza to Ebola and Zika virus disease. As with those previous outbreaks, we must work to stay up to date with the latest data and recommendations, share what we know and do not know with our patients, and continue to be strong advocates for our patients, ensuring that their needs are addressed. Collective action is the only answer for the multiple crises that humanity is facing. The pandemic is reminding us of the importance of multilateralism and international cooperation to face the challenges facing the world today. The United Nations exists for precisely this reason. International cooperation, as well as flexible policies on intellectual property, to access the latest technology and research on potential treatments, including any future vaccine, are necessary to defeat this threat on a global scale. Treatment and vaccines must be considered a global public good. Similarly, the international response to COVID-19 needs global and national statistical systems to collaborate to provide the data and statistical evidence to understand the scope of the pandemic, including disaggregated data to monitor disproportional impacts. |