Eau, Assainissement, Hygiène et SantéBulletin WHEC pratique et de directives cliniques de gestion pour les fournisseurs de soins de santé. Subvention à l'éducation fournie par la santé des femmes et de l'Education Center (WHEC). Safe drinking-water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) for all, are crucial to human health and wellbeing. WASH initiatives are not only a prerequisite to health, but also contributes to livelihood, school attendance, safety at school, healthcare facilities, and dignity. It helps to create resilient communities living in healthy environments. The Women’s Health and Education Center’s (WHEC’s) advocacy and communication global projects and programs, aim to elaborate strategies that strengthens national policies to implement the Sustainable Development Framework. These opportunities are especially designed to help girls, women and minorities so that they also can achieve their full potential. WHEC’s publications are aimed at a broad range of audience, and it is hoped that everyone who reads this comes away with a realization of the complexity of the issues at stake, and an appreciation of the work that lay in front of us. Evidence shows that this can create the transformation necessary to secure more peaceful, fairer and more inclusive societies for everyone, effective multilateralism, and a better globalization. PurposeThe purpose of this document is for healthcare providers and the community to realize the need and necessity to implement WASH projects and programs, to achieve health promoting schools and safe healthcare facilities for all. The objectives are:

Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC) supports and strengthens the generation & collection of data, its analysis, use and dissemination and evidence to promote better evidence-based, decision-making. Its goal is to build capacity in the UN Member States, to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) implementations and achievements, of their populations and the impact of interventions and promote evidence-based policy decisions. SAFE-DRINKING WATERKey Facts

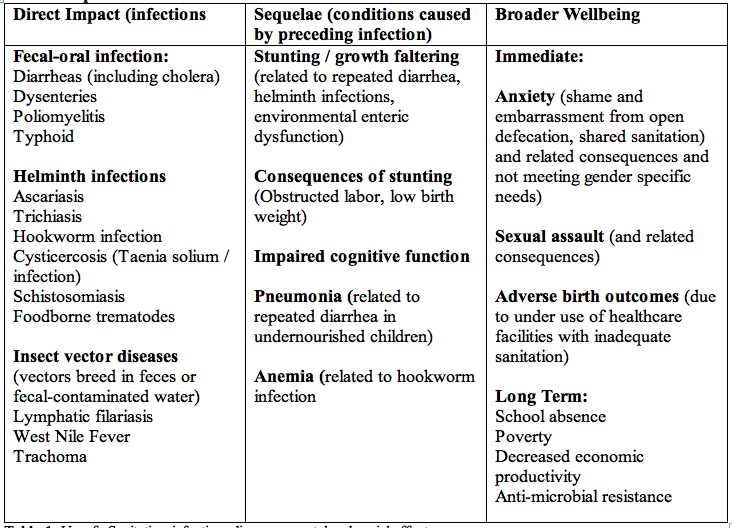

Lessons Learned and The Way ForwardAccording to multiple consultations and multiple stakeholders’ suggestions – universal coverage of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) for all, should be prominent in UN Conferences. There should be a focus on finding solutions and on how to best reach the most marginalized communities. The Women’s Health and Education Center (WHEC) suggests that emphasizing access to technical training, assistance and the exchange of best practices with this field during the conferences and the side events, including strengthening public-private partnerships. WHEC’s best practices and advocacy includes development strategies in the following areas. Inclusion, equity and education: The importance of the interactive dialogues to address inclusion and equity with regard to water resources is also important to Indigenous peoples, women and girls and this should be featured in the UN Conference’s debates. Indigenous peoples are disproportionately impacted by water scarcity due to climate change and the deterioration of the environment, and that these aspects should be included in the decision-making process. Indigenous knowledge must be integrated into decision and policy-making on water. Sustainable solutions require a more inclusive role for nature when creating long-term strategies as well as short term actions. Enhancing natural ecosystem requires participation of a wider range of stakeholders, including Indigenous groups who are at the forefront of environmental protection and sustainability. Water and gender: “It is estimated that each year, a Sudanese girl will miss 95 days of school due to their cycle.” As women are often responsible for managing the household water supply, women’s voices and leadership could enhance effective solutions and sustainable adaption methods. Hence, it would be important for national strategies to create spaces to learn from women’s knowledge, experiences, challenges and concrete solutions. Closing the gender gap in water, sanitation and hygiene is critical. Not having access to clean water impacts all aspects of life of girls and women, including professional, political and social impacts. Clean water as a basic development: Water and Sanitation should be declared as human rights, and this must be available to all. Corruption and mismanagement connected to water supplies and sanitation services should be featured during policy-making decisions. Corruption in the water and sanitation sector affects the fulfillment of human rights and generates serious environmental impacts such as contamination and overexploitation of water sources. Water and conflict: How to resolve the prevent conflicts arising from water scarcity? The increase in conflicts surrounding water, as well as the lack of access to water for refuges and those living in conflict-areas and fragile states, are important topics to be addressed. In this sense, priority must be given to the humanitarian issues arising from water scarcity, inequitable water distribution and using water for peace and security. Water and mental health: Floods and climate change are causing more deaths, damage and impacting mental health. When people perceive or experience a lack of privacy and safety, during open defecation or when using sanitation infrastructure, this can negatively influence their mental and social well-being. The authors of this study found that perceptions and experiences of privacy and safety are influenced by contextual and individual factors, such as location of sanitation facilities and user’s gender identity, respectively. Privacy and safety require thorough examination when developing sanitation interventions and policy to ensure a positive influence on the user’s mental and social well-being. According to UNESCO, studies also link sanitation to attainment of primary and secondary education. The world has seen a dramatic decline in out-of-school rates for both girls and boys in developing countries. Adolescent girls in Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia continue to have a higher out-of-school rate compared to their make classmates. A growing body of literature highlights how poor inaccessible sanitation at school inhibits young girls from safely and comfortably managing their menstruation which may ultimately influence their social and educational engagement, concentration, and attendance WASH and its Impact on Our HealthWASH initiatives are crucial to human health and wellbeing. Safe WASH is not only a prerequisite to health, but contributes to livelihoods, school attendance and dignity and helps to create resilient communities living in healthy environments. Drinking unsafe water impairs health through illnesses such as diarrhea, and untreated excreta contaminates groundwaters and surface waters used for drinking-water, irrigation, bathing and household purposes. This creates a heavy burden on communities. Chemical contamination of water continues to pose a health burden, whether natural in origin such as arsenic and fluoride, or anthropogenic such as nitrates. Safe and sufficient WASH plays a key role in preventing numerous neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) such as trachoma, soil-transmitted helminths and schistosomiasis. However, poor WASH conditions still account for 842,000 diarrheal deaths every year and constrain effective prevention and management of other diseases including malnutrition, NTDs and cholera. Evidence suggests that improving service levels towards safely managed drinking-water or sanitation such as regulated piped water or connections to sewers with wastewater treatment can dramatically improve health by reducing diarrheal disease deaths. WHEC’s Response, Recommendation and Areas of Future Development:

SANITATIONSanitation is defined as access and use of facilities and services for the safe disposal of human urine and fecal waste. A safe sanitation system is a system designed and used to separate excreta from human contact at all steps of the sanitation service chain from toilet capture and containment through emptying, transport, treatment (in-situ or off-site) and final disposal or end use. Safe sanitation system must meet these requirements in a manner consistent with human rights, while also addressing co-disposal of greywater, associated hygiene practices and essential services required for the functioning of technologies. Key Facts

Benefits of Improving SanitationThe benefits of improved sanitation extend well beyond reducing the risk of diarrhea. These include:

According to a study published by the WHO – for every US$1.00 invested in sanitation, there is a return of US$ 5.50 in lower health costs, more productive and fewer premature deaths. ChallengesIn 2010, the UN General Assembly recognized access to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right and called for international efforts to help countries to provide safe, clean, accessible and affordable drinking water and sanitation. Sustainable Development Goal target 6.2, calls for adequate and equitable sanitation for all. The international platform of WHEC on public health with its partners, in 2023, launched advocacy global efforts to prevent transmission of diseases, advising governments and communities on health-based regulation and service delivery. On sanitation. WHEC reports on the global burden of disease and the level of sanitation access and analyses what helps and hinders progress. Such monitoring and reporting gives Member States and donors global data to help decide how to invest in providing toilets and ensuring safe management of wastewater and excreta. Health Impact of Unsafe Sanitation Table 1. Unsafe Sanitation, infectious diseases, mental and social effects. WHEC’s Response, Recommendations and Areas of Future Development:Access and use of safe toilets by the entire community is needed to achieve health gains from sanitation. Without community level coverage, those using safe toilets remain at risk from unsafe sanitation systems and practices by other households, communities, and institutions. In addition, a minimum quality of toilet and containment – storage / treatment is needed to sustain use, to prevent excreta contaminating the local environment and to allow for connection to a safe sanitation chain.

GOOD PRACTICE ACTIONSHealthcare authorities should fulfil their responsibilities to ensure access to safe sanitation in healthcare facilities for patients, staff sanitation in healthcare facilities for patients, staff and carers, and to protect nearby communities from exposure to untreated wastewater and fecal sludge.

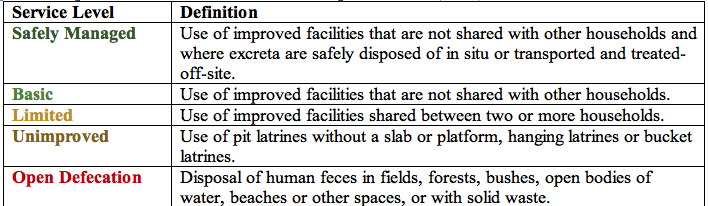

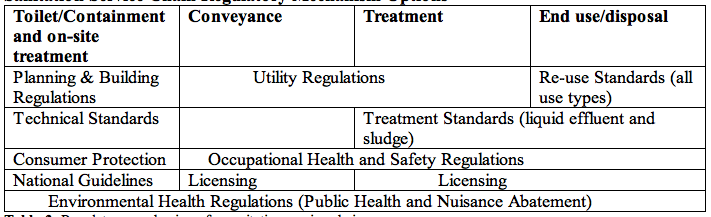

The capacity to deliver universal safe toilet access and promote use varies significantly among and within countries. Efforts will be required to ensure a sufficient legal framework for sanitation, including cooperation to address overlap and inconsistencies. In many low- and middle-income contexts, significant investments will be required to increase the capacity of health authorities and other government departments to improve the demand for and supply of safe toilets. Delivery of sanitation behavior change interventions through health programs may impact on the work-load of health workers (potential increase in terms of activities and supervisory responsibilities, and potential decrease in terms of treatment of infections as well as reliance on mass anthelminthic treatments). The Components of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) in Sanitation and the Ladder Table 2. Based on the recommendations of WHO and UNICEF, (2017). LEGISLATION, REGULATIONS, STANDARDS & GUIDELINESThe legislative framework for sanitation should cover the whole service chain, including both sewered and non-sewered sanitation, to enable the best use of public funds, achievement of standards and attraction of potential service providers. Ensuring adequate standards for sanitation is a government function. Standards and regulations should avoid prescribing specific technologies or systems for particular situations as their suitability can be affected by a multitude of factors. In addition, legislation evolves more slowly than technologies and therefore can impede innovation. Instead, standards and regulations should set out what level of performance is required to achieve a safe sanitation service chain and allow flexibility on how it is achieved. A key area for regulation that applies across the whole service chain is fees and tariffs, for services delivered by utilities, public institutions or entities under their control (e.g. treatment plants under lease or concession arrangements). These may include sewerage fees, fees for use of public or shared toilets, sewerage tariffs, fees for pit emptying by utilities or public institutions, fecal sludge tipping fees, etc. Sanitation Service Chain Regulatory Mechanism Options Table 3. Regulatory mechanisms for sanitation service chain. Risk Assessment and ManagementA risk assessment should guide sanitation interventions to ensure, that sanitation protects public health by managing the risks arising from excreta management, along with the sanitation chain from the toilets to final disposal or use. The risk assessment should identify and prioritize the highest risks and use them to inform system improvements through a mixture of controls along the sanitation chain. Improvements may include technology upgrades, improved operational procedures and behavior change. Risk assessments should be based, as far as possible, on actual conditions, rather than on assumptions of information imported from elsewhere. Frontline government staff such as public health or agricultural extension workers, students, community leaders and community-based organizations can be effective, in data collection if well organized, incentivized and supervised. Regulatory MechanismsThe various steps in sanitation service chains differ in their nature, requiring a corresponding range of regulatory mechanisms. Ways in which the different steps can be regulated are illustrated in Table 3 above. The various mechanisms are highlighted in bold in the following text to facilitate cross-referencing. Additionally, because sanitation cuts across many sectors, relevant legislation and regulation is also widely scattered and elements may be found under:

Sanitation workers are exposed to particular heath risk, and require specific measures to ensure their health and safety. These should include periodic health checks, vaccinations and treatment (e.g. deworming), medical insurance (if available), personal protective equipment (PPE), as well as training in standard operating procedures. The obligation should be for employers to provide all of these, and these requirements should be included in the regulatory arrangements to which employers are subject. Compliance should be verified by health sector personnel (e.g. environmental or occupational health staff). Enforcement and ComplianceAchievements of compliance with standards and regulations requires a broad approach that includes a mix of incentives, promotion and sanctions. Non-coercive means, such as information dissemination, technical assistance, promotion and awards should be used in the first instance. Tax and other fiscal incentives, or privileged access to special services (such as loan guarantees for equipment renovation and purchase) can be economically efficient in some circumstances. When developing regulatory systems, better results are often achieved when it is done in partnership with those being regulated. In this way it is possible to utilize their experience of what is practical and feasible. Such partnering may appear counter-intuitive (service providers might expected to resist regulation), but in most cases, the advantages gained from being formally recognized outweigh any disadvantages that might arise from well-designed regulation. National guidelines should be produced advising how to apply enforcement, and training provided on how to manage legal proceedings, particularly the collection and presentation of evidence. Responsible managers should review the enforcement activity and report on it annually, highlighting any sanitation issues that arise, and checking that it is not being applied abusively. Sanitation in Healthcare FacilitiesHealthcare facilities represent a particularly high sanitation risk, due to both infectious agents and toxic chemicals. From the user perspective they should be a model of hygienic sanitation. Healthcare facility sanitation should be the responsibility of the Ministry of Health, with responsibility for its management clearly specified in the job descriptions of healthcare facility managers and relevant staff. Recommended numbers of toilets are 1:20 for inpatients and at least two toilets for outpatient settings (one toilet dedicated for staff and one gender-neutral toilet patient that has menstrual hygiene facilities and is accessible for people with limited mobility). They should be culturally acceptable, private, safe, clean and accessible to all users, including provision for those with reduced mobility and for menstrual hygiene management. Bedpans should be used by patients only when needed, and not as a regular substitute for toilets; when used, bedpans should be safely handled avoiding spillage and using appropriate PPE. Fecal waste from bedpans and water used for washing bedpans should be emptied into a toilet or into the sanitation system through other means such as a drain or macerator. A reliable water point with soap should be available close to the toilet for handwashing. Immediate Preventive Measure for Areas at High-Risk of Enteric Disease OutbreaksNeighborhood and Household Level

Promote and support the installation of handwashing facilities in homes and institutions. Medium Term Measures

At Health-posts, Hospitals or Emergency Facilities for Infected People Immediate Measures

Medium Term Measures

Fecal Sludge Management Immediate Measures

Medium Term Measures

A budget for the operation and maintenance of the healthcare facilities wastewater system must be consistently allocated. An adequately trained staff member should have officially designated responsibility for the system, with staff allocated to maintenance tasks. Imagining a better future: A dramatic acceleration in progress is possibleInvestment in five key ‘accelerators’ – governance, financing, capacity development, data and information, and innovation – are identified under UN-Water SDG 6 Global Acceleration Framework. It can be a pathway towards countries’ achievement of safe sanitation for all, with coordinated support for the multilateral system and partners. Governments MUST ensure that coverage extends to entire communities, deploying a mix of approaches and services. Sanitation coverage must extend beyond the household, do that everyone in schools, healthcare facilities, workplaces and public places has access. WHEC's call to transform sanitation for better health, environment, economies and societies are:

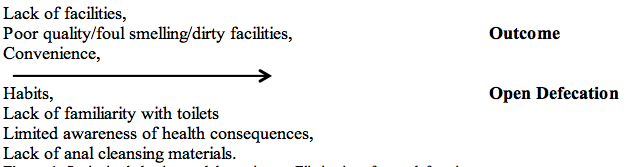

Increased urbanization and migration call for new ways of meeting the needs of high-density populations living in poverty, often in informal settlements. By presenting best practices, case studies, successes and challenges, our efforts seek to inspire Member States and all stakeholders to learn from each other and work together towards achieving universal access to safe sanitation by 2030. Sanitation Behaviors and DeterminantsGovernments are the critical stakeholder in the coordination and integration of behavior change initiatives at the local level and should provide leadership and ensure funding. The sanitation behavior change requires financial and human resources, and that failure to commit sufficient resources may lead to failure to achieve sustained adoption or use of household sanitation services. The Ministry of Health may be involved in the formulation of sanitation behavior change strategies, in the setting of targets, and in the development of local guidelines. Behavioral Determinants for Open Defecation Figure 1. Sanitation behaviors and determinants. Elimination of open defecation. Changing Behaviors – Main ApproachesWhile myriad strategies have been used, these typically fall into one or more of four major categories:

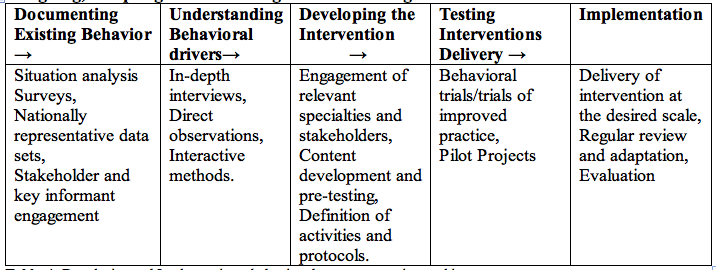

Stages in Behavior Change Strategy DesignSanitation interventions and the safe disposal of human excreta have the potential to impact on the transmission of a diverse range of microbial hazards. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) among the human pathogens has been identified as one of the greatest global threats to human health. AMR arises from genetic mutations that allow the emergence of new bacterial strains that are not affected by an antimicrobial agent. This can occur in the body of a host or in environmental settings where the presence of antimicrobial agent kills off the main populations of the target bacteria and allows the remaining resistant strains to flourish. There are potentially three distinct types of monitoring necessary for successful sanitation behavior change program. These include:

Designing, Adapting and Delivering Behavior Change Interventions Table 4. Developing and Implementing a behavior change strategy is a multi-stage process. Regardless of the approach use, attention should be given to the frontline workers who are engaged in the direct delivery of sanitation behavior change activities. SUMMARYBetter access to water is helping create new possibilities for people in some of the world's most remote communities. Goal 6 of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is ensuring availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. WATER is at its core of SDGs and is critical for socio-economic development, energy and food production, healthy ecosystems and for human survival itself. Water is also at the heart of adaptation to climate change, serving as the crucial link between society and the environment. Water is also a human rights issue. As the global population grows, there is an increasing need to balance all of the competing commercial demands on water sources, so that communities have enough for their needs. In particular, women and girls must have access to clean, private sanitation facilities to manage menstruation and maternity in dignity and safety. Sanitation plays a role in improving broader aspects of health, including gender, security, quality of life and overall wellbeing. Environmental health delivered through critical health sector functions is essential in preventing a significant proportion of the burden of disease globally; these functions are:

Successful programming outcomes for sanitation are more likely to be successful, where coordination and collaboration between different sectors and stakeholders exists, affecting both the scale and effectiveness of sanitation programs. Lower prevalence or incidence of diseases is associated with greater access to sanitation, particularly for diseases and conditions that continue to inflict a health burden in low-income settings including diarrhea, soil contaminated helminth infections, trachoma, cholera, schistosomiasis, and poor nutritional status. SUGGESTED READINGWater & Sanitation: Essential for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Implementation for Schools and Healthcare facilities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, SDG 6 National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIH) World Health Organization (WHO) |