新生儿营养WHEC实践公报和临床管理准则的医疗保健提供商。教育补助金所提供妇女保健和教育中心( WHEC ) 。 The landscape of breastfeeding has changed over the past several decades as more women initiate breastfeeding in the postpartum period and more hospitals are designated as Baby-Friendly Hospitals by following the evidence-based Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. The number of births in such facilities has increased more than six-fold over the past decade. There are diverse and important advantages to infants, mothers, families and society for breastfeeding and the use of human milk for infant feeding. These include health, nutritional, immunologic, developmental, psychological, social, economic, and environmental benefits. Human milk feeding supports optimal growth and development of the infant while decreasing the risk of a variety of acute and chronic diseases. Healthcare providers evaluate breastfeeding infants and their mothers in the office setting frequently during the first year of life. The office setting should be conducive to providing ongoing breastfeeding support. Even mothers who are initially undecided or hesitant to breastfeed usually can do so successfully with appropriate counseling, education, and knowledgeable support, including that of a certified lactation consultant. The purpose of this document is to review practices shown to support breastfeeding that can be implanted in the outpatient setting, with the goal of increasing the duration of exclusive breastfeeding and the continuation of any breastfeeding. Formula feeding should not be portrayed as equivalent to human milk feeding. If the mother chooses not to breastfeed after these interventions have been implemented, she should be supported in her decision. BackgroundSupport of successful breastfeeding begins during pregnancy. Breastfeeding has long been documented as the ideal method for feeding and promoting the optimal development of infants and children, with rare exception (1). Benefits of breastfeeding include decreased risk of lower respiratory infections, gastroenteritis, otitis media, and necrotizing enterocolitis, and later being especially important in preterm infants. Because breastfeeding is the norm for infant feeding, comparatively there are risks associated with the lack of breastfeeding, which include an increase in sudden infant death syndrome, obesity, asthma, certain childhood cancers, diabetes, and post-neonatal death (2). Breastfeeding promotes attachment and optimal cognitive development. In women lack breastfeeding is associated with an increase in the risk of breast and ovarian cancer, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and postpartum depression (3),(4). In the United States, The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for approximately 6 months, followed by continued breastfeeding for 1 years or longer, as mutually desired by mother and child (1). The Surgeon General's Call to Action To Support Breastfeeding in 2011 emphasized the importance of breastfeeding as a public health imperative (5). The Women's Health and Education Center (WHEC) and its partners call on its partners and members, to actively engaged in promoting and supporting breastfeeding among their patients. Initiation of BreastfeedingPrenatal care should include discussion of prior breastfeeding experience, feeding plans, and breast care. Ascertaiment of a history of breast surgery, trauma, or prior lactation failure is important because these situations may present special challenges to successful breastfeeding. A healthy-newborn infant can latch on to the breast without specific assistance within the first hour after birth, and breastfeeding should be initiated within the first postnatal hour unless medically contraindicated. Appropriately triaged healthy term infants should be placed in direct skin-to-skin contact with their mothers and allowed to attempt breastfeeding immediately after birth and should remain there, with frequent assessments by hospital personnel. Care should be taken to monitor the infant's nose to avoid positions that obstruct breasting, which may lead to collapse. Skin-to-skin care should be encouraged throughout the postpartum stay, whenever possible. Rooming-in with the mother facilitates breastfeeding. The mother should be encouraged to offer the breast whenever the infant shows early signs of hunger (e.g. increased alertness, increased physical activity, mouthing, or rooting), not to wait until the infant cries. When awake, the newborn infant should be encouraged to feed frequently (8-12 breastfeedings every 24 hours) until safely to help stimulate milk production. Scheduling specific times for feeding is not encouraged. In the early weeks after birth, an infant may need to be aroused to feed if 4 hours have elapsed since the last nursing. This is especially true for a late-preterm infant. Usually, it is practical to alternate the breast used to initiate the feeding and equalize the time spent at each breast over the day. Supplemental feedings including water, glucose water, formula, and other fluids should not be given to the breastfeeding infant unless ordered by the healthcare provider after documentation of a medical indication. Intermittent bottle-feeding of a breastfed newborn infant may lessen the success of breastfeeding (6). If the infant's appetite is partially satisfied by supplements, the infant will take less from the breast, and milk production will be diminished. EpidemiologyThe rate of initiation of any breastfeeding in the US population is 81.1%, as surveyed in 2016 (7). Although the rate of breastfeeding initiation approaches the Healthy People 2020 target of 81.9%, only 22.3% of US infants are breastfed at age 6 months (8). There are significant disparities in terms of breastfeeding rates in the country; among black infants, only 66.3% are breastfed at all, and only 14.6% are exclusively breastfed through the first 6 months of life. Among Native American and Alaska Native infants, breastfeeding initiation is 68.3% and exclusive breastfeeding rates at 6 months are 17.9%. Mothers are more likely to breastfeed if they are married, have a college education, live in metropolitan areas, do not experience poverty, and do not receive benefits from Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). WIC provides targeted breastfeeding support and peer-counseling services for mothers who qualify for their services. Infants most likely to experience toxic stress are least likely to be breastfed. According to the 2005-2007 Infant Feeding Practices Study II, 85% of US mothers intended to breastfeed exclusively for >3 months; however, only 32.4% achieved their intended exclusive breastfeeding duration (9). The Ten Steps to Successful BreastfeedingThere is no doubt regarding the multiple benefits of breastfeeding for infants and society in general. Therefore, the World Health Organization (WHO) in conjoint effort with United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) developed the "Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding" in 1992, which became the backbone of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI). Following this development, many hospitals and countries intensified their position towards creating a "breastfeeding oriented" practice (10). Over the past two decades, the interest increased in the BFHI and the Ten Steps. However, alongside the implementation of the initiative, extensive research continues to evaluate the benefits and dangers of the suggested practices. Hence, it is our intention to make a critical evaluation of the current BFHI and the Ten Steps recommendations in consideration of the importance of providing an evidence-based breastfeeding supported environment for our mothers and infants.

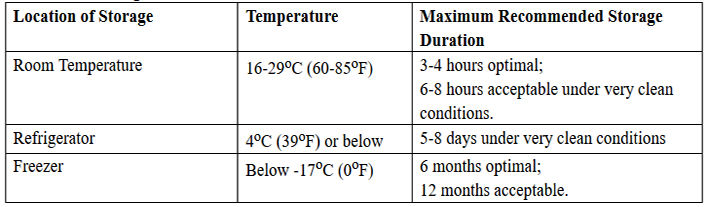

For the national breastfeeding targets to be met, outpatient support from pediatricians and other health care providers is imperative. As more infants are being discharged from hospitals designated as Baby-Friendly and having successfully initiated breastfeeding, it is essential that the pediatricians with whom they will follow up are knowledgeable about breastfeeding and that their office practices are prepared to support these breastfeeding practices and policies. A pediatrician or other knowledgeable and experienced health care professional should see the newborn infant at 3-5 days of age or within 48 hours of discharge. A secondary appointment should be scheduled when infant is 2-3 weeks of age to monitor progress. Monitoring Breastfeed NewbornTracking an infant's weight provides a useful assessment of adequacy of breast milk intake. Weight can be plotted on hour-specific curves for vaginal or cesarean delivery to assist with determining when a term infant requires a careful evaluation of the feeding techniques being used and the adequacy of breastfeeding (11). Excessive or prolonged infant weight loss should prompt a thorough evaluation by the pediatric care provider. Close monitoring of the infant and consideration of supplementation with infant formula should be considered. Although previous literature suggested that a failure to regain birth weight by 10 days required further evaluation, a very large population-based study found that only about one half of infants had regained their birth weight on the appropriate graph can provide guidance on the need for further evaluation (12),(13). Although delayed onset of lactogenesis is relatively common, true failure of lactogenesis occurs far less frequently, and with support, breastfeeding occurs far less frequently, and with support, breastfeeding can usually be established. Exclusive breastfeeding is the ideal nutrition and is almost always sufficient to support optimal growth and development for the healthy term infant for approximately 6 months after delivery. In families with a strong history of allergy, breastfeeding is likely to be especially beneficial. Infants weaned before the age of 12 months should not receive cow's milk feeding; instead, they should receive iron-fortified infant formula. Contraindication to BreastfeedingContraindications to breastfeeding include certain maternal infectious diseases and medications. A mother with active herpes simplex virus infection may breastfeed her infant if she has no vesicular lesions in the breast area, if she observes careful hand hygiene. A mother who has herpes simplex lesions on a breast should not breastfeed her infant on that breast until the lesions are cleared. Endometritis and mastitis that is being treated with antibiotics is not a contraindication to breastfeeding. The situations that are not in the best interest of the infant for breastfeeding are: newborn infant with classic galactosemia (who must be fed non-lactose-based formula), the newborn infant whose mother is positive for human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type I or II, and the newborn infant whose mother uses non-medical drugs. In situations where maternal breast milk confers specific medical advantages (i.e. very-low-birth-weight infants), the clinician must weigh the risks and benefits of formula versus maternal milk, which may be contaminated by non-medical drugs (e.g. tetrahydrocannabinol). In the US and other developed countries where formula is safe and readily available, women infected with HIV should not breastfeed their infants. Mothers who receive certain radioactive materials should not breastfeed if there is radioactivity in the milk, and mothers who are receiving antimetabolites or chemotherapy should not breastfeed until the medication has cleared from the milk. Rarely, a specific vaccine, such as live-attenuated rabies, is contraindicated during breastfeeding. Please visit the guidelines stated by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for updated information (15). Breast milk provides protections against many respiratory diseases, including influenza (flu). A mother with suspected or confirmed flu should take all possible precautions to avoid spreading the virus to her infant while continuing to provide breast milk to her infant. Flu is not spread to infants through breast milk (16). When an infant has flu, the mother should be encouraged to continue breastfeeding or feeding expressed breast milk to her infant. Flu vaccination is safe for breastfeeding women and their infants aged 6 months and older. Human Milk StorageThere are many situations in which a mother might be separated from her infant, necessitating her to express and store her breast milk. A mother who is in school or employed outside of the home can maintain exclusive human milk feeding by providing expressed milk to be given in her absence; therefore, it is important to encourage and support mothers in providing their infants with expressed milk. All mothers who provide milk for their infants should be instructed in the proper techniques of milk collection and storage to minimize bacterial contamination. Careful hand hygiene is critical before handling the breast, the equipment, or the milk. Previous practices of washing the breast and discarding the first expressed milk did not result in a decrease in bacterial colonization of milk, and therefore, are not necessary (17). Although manual expression, when performed correctly, yields relatively uncontaminated milk, many women prefer to use a breast pump. All parts of the pump that are in contact with the milk should be washed carefully with hot, soapy water, and rinsed and dried thoroughly after each use. The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine recommends that fresh expressed milk be stored in sterile glass or plastic containers or plastic bags that are free of bisphenol A and made specifically for human milk storage. According to the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, milk that is refrigerated (at or below 4oC [39oF]) should optimally be used within 72 hours, although 5-8 days is acceptable under very clean conditions (18). Frozen milk should optimally be stored for up to 6 months, although 12 months is acceptable. Breast Milk Storage Guidelines Human milk should not be defrosted in extremely hot water or in a microwave oven. The very high temperatures that may be reached with these methods can destroy valuable components of the milk and may result in thermal injury to the infant. Previously frozen milk thawed for 24-hours should not be left at room temperatures for more than a few hours because of its reduced ability to inhibit bacterial growth. Whether thawed breast milk can be safely frozen is uncertain. When using human milk in neonatal care units, it is essential to have policies and procedures for storing in milk, appropriately identifying the milk, and checking the milk before giving it to an infant. Infant OutcomesTo date, the most comprehensive publication that reviews and analyzes the published scientific literature that compares breastfeeding and commercial infant formula feeding as to health outcomes is the report prepared by the Evidence-based Practice Centers of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) of the US Department of Health and Human Services titled: Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Developed Countries (19). The following analysis summarize and update AHRQ meta-analyses and provide and expanded analysis regarding health outcomes: Respiratory Tract Infections and Otitis Media Any breastfeeding compared with exclusive commercial infant formula feeding will reduce the incidence of otitis media by 23% (21). Exclusive breastfeeding for more than 3 moths reduces the risk of otitis media by 50%. Serious colds and ear and throat infections were reduced by 63% in infants who exclusively breastfed for 6 months (21). Gastrointestinal Tract Infections and Necrotizing Enterocolitis Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) and Infant Mortality It has been calculated that more than 900 infant lives per year may be saved in the United States if 90% of mothers exclusively breastfed for 6 months. In the 42 developing countries in which 90% of the world's childhood deaths occur, exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and weaning after 1 year is the most effective intervention, with the potential of preventing more than 1 million infant deaths per year, equal to preventing 13% of the world's childhood mortality (24). Allergic Disease Celiac Disease and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Breastfeeding associated with a 31% reduction in the risk of childhood inflammatory bowel disease (26). The protective effect is hypothesized to result from the interaction of the immunomodulating effect of human milk and the underlying genetic susceptibility of the infant. Different patterns of intestinal colonization in breastfed versus commercial infant formula-fed infants may add to the preventive effect of human milk. Obesity Diabetes Childhood Leukemia and Lymphoma Neurodevelopment Outcomes Donor Human Milk, Pasteurization and DistributionThe use of donor human milk is increasing for high-risk infants, primarily for infants born weighing <1,500 g or those who have severe intestinal disorders. Pasteurized donor milk may be considered in situations in which the supply of maternal milk is insufficient. The use of pasteurized donor milk is safe when appropriate measures are used to screen donors and collect, store, and pasteurize the milk and then distribute it through established human milk banks. The use of non-pasteurized donor milk and other forms of direct, Internet-based, or informal human milk sharing does not involve this level of safety and is not recommended. It is important that health care providers counsel families considering milk sharing about the risks of bacterial or viral contamination of non-pasteurized human milk and about the possibilities of exposure to medications, drugs, or herbs in human milk (31). Currently, the use of pasteurized donor milk is limited by its availability and affordability. The development of public policy to improve and expand access to pasteurized donor milk, including policies that support improved governmental and private financial support for donor milk banks and the use of human milk, is important. Donor milk banks represent safe and effective approach to obtaining, pasteurizing, and dispensing human milk for use in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and other settings. However, accessibility to donor milk in the United States continues to be substantially limited in terms of supply, cost, and distribution. The number of human milk banks in the United States is increasing. Currently, there are 20 donor milk banks in the United States and 4 in Canada that pasteurize milk as part of a professional organization for supporters of non-profit human milk banking, the Human Milk Banking Association of North America (HMBANA); 7 others are in various stages of planning and development. HMBANA has established policies for donor milk collection, as do commercial human milk banks (32). Pasteurization Distribution Safety The process of pasteurization destroys cells, such as neutrophils and stem cells, and affects macronutrients and anti-inflammatory factors. In addition, pasteurization can eliminate bacterial strains with probiotic properties. Substantial evidence describing these losses is available (33). Bioactive components of human milk, including lactoferrin and immunoglobulins, are substantially decreased by pasteurization, but there is much less effect on macro- and micronutrients, including vitamins (33). Overall, the benefits of improved feeding tolerance and clinical outcomes support the concept that some nutrient losses of bioactive components should not limit the use of donor milk or preclude its pasteurization before use. Pacifier UseGiven the documentation that early use of pacifiers may be associated with less successful breastfeeding, pacifier use in the neonatal period should be limited to specific medical situations (34). These include uses for pain relief, as a calming agent, or as part of structured program for enhancing oral motor function. Because pacifier use has been associated with a reduction in SIDS incidence, mothers of healthy term infants should be instructed to use pacifiers at infant nap or sleep time after breastfeeding is well established, at approximately 3 to 4 weeks of age (34). Vitamins and Mineral SupplementsIntramuscular vitamin K1 (phytonadione) at a dose of 0.5 to 1.0 mg should routinely be administered to all infants on the first day to reduce the risk of hemorrhagic disease of newborn (35). A delay of administration until after the first feeding at the breast but not later than 6 hours of age is recommended. A single oral dose of vitamin K should not be used, because oral dose is variably absorbed and does not provide adequate concentrations or stores for breastfed infant (35). Vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency and rickets has increased in all infants because of decreased sunlight exposure secondary to changes in lifestyle, dress habits, and use of topical sunscreen preparations. To maintain an adequate serum vitamin D concentration, all breastfed infants routinely should receive an oral supplement of vitamin D 400 U per day, beginning at hospital discharge (36). Supplementary fluoride should not be provided during the first 6 months. From age 6 months to 3 years, fluoride supplementation should be limited to infants residing in communities where the fluoride concentration in water is <0.3 ppm (37). Complementary food rich in iron and zinc should be introduced at about 6 months of age. Supplementation of oral iron drops before 6 months may be needed to support iron stores. Premature infants should receive both a multivitamin preparation and an oral iron supplement until they are ingesting a completely mixed diet and their growth and hematologic status are normalized. Recommendations Regarding Consumption of Raw or Unpasteurized Milk and Milk ProductsFoodborne illness accounts for substantial morbidity and mortality in the United States. Estimates suggest that each year, as many as 48 million Americans experience foodborne illness, accounting for 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths (38). Among the most preventable of these foodborne illnesses are infections related to ingestion of raw or unpasteurized milk and milk products, because of ubiquitous access to healthy, pasteurized milk and milk products, as well as legislation prohibiting the sale of raw dairy products in much of the United States. Pasteurization of milk in the United States began in 1920s. although most milk and milk products consumed today in the United States are pasteurized, an estimated 1% to 3% of all dairy products consumed in the United States are not pasteurized (39). Sales of raw or unpasteurized milk and milk products are still legal in at least 30 states in the United States. Raw milk and milk products from cows, goats, and sheep continue to be a source of bacterial infections attributable to several virulent pathogens, including Listeria monocytogenes, Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella species, Brucella species, and Escherichia coli. These infections can occur in both healthy and immunocompromised individuals, including older adults, infants, young children, and pregnant women and their unborn fetuses, in whom life-threatening infections and fetal miscarriage can occur. Efforts to limit the sale of raw milk products have met with opposition from those who are proponents of the purported health benefits of consuming raw milk products, which contain natural or unprocessed factors not inactivated by pasteurization. However, the benefits of these natural factors have not been clearly demonstrated in evidence-based studies, and therefore, do not outweigh the risks of raw milk consumption (40). Substantial data suggest that pasteurized milk confers equivalent health benefits compared with raw milk, without additional risk of bacterial infections. The Women's Health and Education Center (WHEC) strongly supports the national and international associations in endorsing the consumption of only pasteurized milk and milk products for pregnant women, infants and children. WHEC also endorses a ban on the sale of raw or unpasteurized milk and milk products throughout the United States, including the sale of certain raw milk cheeses, such as fresh cheeses, soft cheeses, and soft-ripened cheeses. This recommendation is based on the multiplicity of data regarding the burden of illness associated with consumption of raw and unpasteurized milk and milk products, especially among pregnant women, fetuses and newborn infants, and infants and young children, as well as strong scientific evidence that pasteurization does not alter the nutritional value of milk. SummaryResearch and practice in the last two decades have reinforced the conclusion that breastfeeding and use of human milk confer unique nutritional and non-nutritional benefits to the infant and the mother, and in turn, optimize infant, child, and adult health as well as child growth and development. Recently, published evidence-based studies have confirmed and quantitated the risk of not breastfeeding. Thus, infant feeding should not be considered as a lifestyle choice but rather as a basic health issue. As such, the healthcare provider's role in advocating and supporting proper breastfeeding practices is essential and vital for the achievement of this preferred public health goal. The Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the US Department of Health and Human Services, with support from the Office of Women's Health, has created a program, "The Business Case for Breastfeeding," that provides details of economic benefits to the employer and toolkits for the creation of such programs. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act passed by Congress in March 2010 mandates that employers provide "reasonable break time" for nursing mothers and private non-bathroom areas to express breast milk during their workday. The establishment of these initiatives as the standard workplace environment will support mothers in their goal of supplying only breast milk to their infants beyond the immediate postpartum period. References

|