حديثي الولادة المعرضون لفيروس نقص المناعة البشرية: الوقاية والتقييم والإدارة[وهك] ممارسة نشرة وسريرية إدارة لمقدمي الرعاية الصحية. قدمت منحة للتربية وصحة المرأة وتربية مركز ([وهك]). Healthcare providers play a crucial role in optimizing the prevention of perinatal transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection. Fewer infants are infected with HIV through mother-to-child transmission, making HIV-exposed but uninfected infants a growing population. HIV-exposure seem to affect immunology , early growth and development, and is associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates. Considerable strides have been made in reducing the rate of perinatal HIV transmission within the United States and around the globe. Despite this progress, preventable perinatal HIV transmission continues to occur. Adherence to HIV screening and treatment recommendations preconception and during pregnancy can greatly reduce the risk of perinatal HIV transmission. Early and consistent usage of highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART) can greatly lower the HIV viral load, thus minimizing HIV transmission. Additional intrapartum interventions can further reduce the risk of HIV transmission. Although the current standard is to recommend abstinence from breastfeeding for individuals living with HIV in settings where there is safe access to breast milk alternatives (such as in the United States), there is guidance available on counseling and risk-reduction strategies on ART with an undetectable viral load who elect to breastfeed. Currently, there is a lack of information regarding the clinical effects of HIV-exposure during neonatal period. The purpose of this document is to discuss the evaluation and management of the newborns exposed to HIV. Perinatal HIV transmission is the leading cause of childhood HIV infection. Despite improved knowledge, medications, and access to care, HIV continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. HIV-exposed but uninfected neonates have higher rates of neonatal sepsis, particularly late-onset sepsis, require more respiratory support and have higher rates of lung disease. This review offers guidance on the evaluation and management of infants born to women with HIV infection. In addition to standard clinical care for the newborn infant, it is important that appropriate steps are taken for early detection of HIV infection, appropriate vaccines are administered, and adequate counseling is provided to families living with HIV infection. BackgroundHuman Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is one of the world's biggest health threats. In 2018, the Republic of South Africa had the third highest prevalence of HIV in the world, with 20.4% of adults infected with according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimations, which equals 7.5 million people (1). In addition, 260,000 children between the ages of 0 - 14 years of are infected. One of the biggest tragedies of the epidemic, is the transmission of the virus from mother-to-child, which can occur in utero, intrapartum or postnatally (predominantly through the breastfeeding). HIV infection during infancy has a high risk of mortality, with a net survival of 52% at 1-year if infected perinatally and 78% at 1-year post-infection, if infected through breastfeeding (2). IntroductionEach year approximately 8,500 women with HIV infection give birth in the United States (3). Through the implementation of effective, cost-saving preventive strategies during pregnancy, the rate of perinatal transmission of HIV has remained low at <1% to 2% These preventive strategies include (4):

Pre-pregnancy CounselingAll people, regardless of HIV status, should be counseled regarding safe sex practices and offered HIV and other sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening. Such screening includes at least one-time HIV testing in everyone 13 - 64 years of age, as well as annual or more frequent HIV testing in high-risk individuals (people with a sexual partner living with HIV, people who use injection drugs or partners of people who use injection drugs, people who exchange sex for money or drugs, and people who themselves or whose sex partners have had more than one sex partner since their last HIV test). Additionally, all people considering pregnancy should receive HIV testing as part of routine preconception care (5). Identification of Maternal HIV InfectionIn the United States, HIV testing is now part of routine prenatal care in most states unless the patient declines, which is also known as "opt-out" consent or "right to refusal" (6). A second HIV test during the third-trimester, preferably before 36 weeks' gestation, has been found to be cost effective even in low-prevalence areas and should be considered for all pregnant women (7). In particular, pregnant women at high risk for incident HIV infection (e.g., those who are incarcerated, reside in communities with in HIV incidence greater than 1 per 1,000 per year, inject drugs, exchange sex for money or drugs, are sex partners of individuals living with HIV, or have had a new or more than one sex partners during current pregnancy) should have HIV testing repeated in the third trimester. A plasma HIV RNA test is recommended in addition to routine antigen/antibody immunoassay testing when the possibility of acute retroviral syndrome is suspected in a pregnant woman. Testing of Infant - When the Mother's HIV Infection Status is UnknownWhen the HIV status of the mother is unknown, expedited HIV testing should be performed on the infant after consent procedures consistent with state and local law. Expedited HIV antigen/antibody testing allows timely identification of HIV infection in women whose HIV status is unknown late in pregnancy, during labor, or in the immediate postpartum period and is generally available on a 24-hour basis at all facilities with maternity services and/or a neonatal care unit. Positive HIV antigen/antibody test results should be urgently reported to healthcare providers so that presumptive HIV therapy can be initiated in the infant, as soon after birth as possible, and ideally within 6 to 12 hours of life. In addition, breastfeeding should be postponed, and the infant should be given formula feedings. If supplemental test results are negative, antiretroviral drugs should be stopped, and breastfeeding may be reinstated (8). FRAMEWORK FOR THE TOTAL ELIMINATION OF PERINATAL TRANSMISSION OF HIVSeveral strategies have been documented that could potentially lead to elimination of perinatal transmission of HIV.

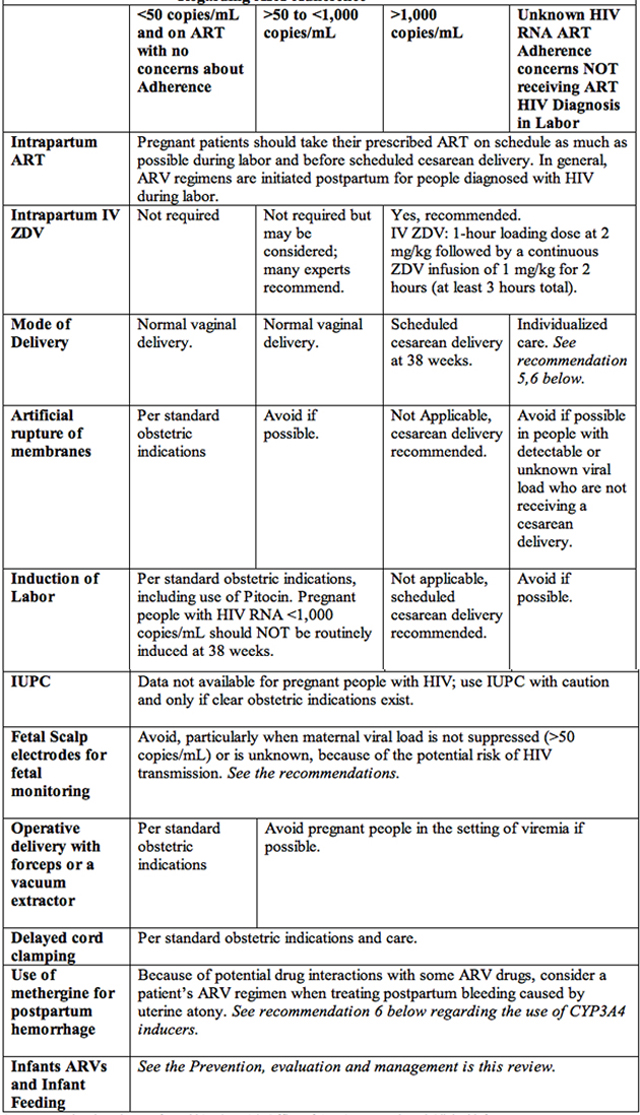

PREVENTION OF MOTHER-TO-CHILD TRANSMISSION: ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY (ART) and DRUGS ADHERENCE All individuals with HIV should be receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) or initiate ART in pregnancy as early as possible to suppress HIV RNA to undetectable levels (<50 copies/mL). Current recommendations are that pregnant patients with HIV + with HIV RNA>1,000 copies/mL or unknown HIV RNA near the time of delivery should receive a 1-hour loading dose of zidovudine (ZDV) at 2 mg/kg followed by a continuous IV ZDV infusion of 1 mg/kg for 2 hours (minimum 3 hours total). Pregnant patients should be delivered according to standard obstetric indications; labor should not be induced at 38 weeks, for prevention of perinatal HIV transmission. Patients with HIV who present late in pregnancy and are not receiving ART drugs may not have HIV RNA results available before delivery, should have cesarean delivery. Summary of recommendations are (8): HIV RNA at Time of Delivery

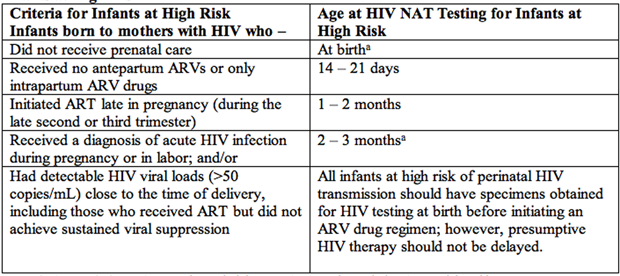

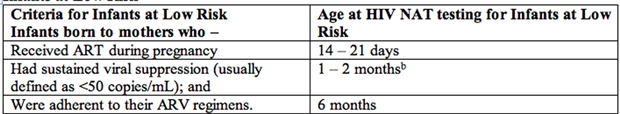

Care of Exposed Infant to HIVTesting to Determine the Infant's HIV Infection Status Appropriated HIV diagnostic testing for infants and children younger than 18 months differs from that for older children, adolescents, and adults. Passively transferred maternal HIV antibodies may be detectable in an exposed but an infected infant's bloodstream until approximately 18 months of age. Therefore, routine serological testing of infants exposed to HIV and children before the age of 18 months is generally only informative if the test result is negative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays that directly detect HIV DNA or RNA (generically referred to as HIV nucleic acid amplification tests [NAATs]) represent the gold standard for diagnostic testing of infants and young children younger than 18 months. With such testing, the diagnosis of the presumptive exclusion of HIV infection can be established within the first several weeks of life among non-breastfed infants. Although neonatal antiretroviral therapy (ART) and drugs may decrease the concentration of HIV RNA in infant plasma, in the first 6 weeks of life, HIV DNA PCR results generally remain positive in the most individuals taking ART who have undetectable plasma HIV RNA (11). The sensitivity of both DNA and RNA PCR testing is high, so can be used for the diagnosis of HIV infection in infancy (12). False-positive results with low-level viral copy numbers have been described when using HIV RNA assays, reinforcing the importance of repeating any positive assay result to confirm the diagnosis of HIV infection in infancy. False-negative results occur rarely, and retesting could be considered (perhaps by using a different test) if clinical findings suggest the presence of HIV infection. Detection of Non-Subtype B HIV and HIV-2 For infants born to women known or suspected to have infection with non-B subtypes of HIV, use of HIV RNA assays may be preferable to the use of HIV DNA assays for diagnostic testing. Women who acquire HIV infection in North America are most commonly infected with HIV subtype B (13). Women who acquire HIV outside of North America are often infected with other HIV subtypes. Subtypes C and D predominate southern and eastern Africa, subtype C predominates on the Indian subcontinent, and subtype E predominates in much of Southeast Asia (13). HIV DNA PCR assay may be less sensitive in the detection of non-B subtype HIV, and false-negative HIV DNA PCR assay results have been reported in infants infected with non-B subtype HIV (14). Some of the currently available HIV RNA assays have improved sensitivity for detection of non-B subtype HIV infection, although even these assays may not detect all non-B subtypes, such as the uncommon group O HIV strain. When testing infants suspected of infection with non-B subtyped HIV, consultation with a pediatrician experienced in the care of infants and children with HIV infection is recommended. HIV-2 is a retrovirus similar to HIV and is found most commonly in western Africa. It is less virulent, with a slower rate of progression of clinical disease and lower rates of perinatal transmission. However, NAATs for HIV will not identify HIV-2, so if infection with HIV-2 is suspected, consultation with the CDC via the state department of health may be sought to help arrange specific HIV-2 testing (15). Timing of Diagnostic Testing in Infants with Known Perinatal Exposure to HIV For infants with known perinatal exposure, it is recommended that diagnostic testing with HIV DNA or RNA assays be performed at 14 to 21 days of age, and if results are negative, they should be repeated at 1 to 2 months of age and again at 4 to 6 months of age (16). See Table 2 and 3 below. For infants at a higher risk of perinatal HIV transmission who receive multiple antiretroviral (ARV) drugs, additional virological diagnostic testing at birth as well as 2 to 4 weeks after cessation of antiretroviral prophylaxis should be considered (17). An HIV NAAT should be performed at birth and in the few days of life for infants at highest risk of infection, including, those whose mothers received no ARV drugs during pregnancy, when maternal prophylaxis was started late in pregnancy or during labor, or if the mother had primary HIV infection during pregnancy. In the absence of maternal ART, as many as 30% to 40% of infants with HIV infection can be identified after 48 hours of age. Infants with a positive NAAT result at or before 48 hours of age are considered to have in utero infection with HIV, whereas infants who have a negative NAAT result during the first week of life and a subsequent positive test result are considered to have intrapartum infection (18). Cord blood specimens are not used for HIV RNA or DNA testing because they are associated with an unacceptable high rate of false-positive test results. Recommended Virologic Testing SchedulesInfants at High Risk  Infants at Low Risk  Interpretation of Negative HIV Test ResultsOn the basis of analysis of HIV DNA or RNA assay results from multiple studies, the CDC in USA has revised the case definition for exclusion of HIV infection in infants for surveillance purposes (18). The definitions supplied here are based on the CDC surveillance definitions and are appropriate for the management of children born to women with HIV infection. These definitions of exclusion of HIV infection are only for use in infants who do not meet the criteria for HIV infection noted above. In non-breastfeeding infants younger than 18 months with no positive HIV NAAT results, presumptive exclusion of HIV infection is based on the following:

Definition exclusion of HIV infection in a non-breastfed infant is based on the following:

Discussion: Many experts confirm the absence of HIV infection with a negative HIV antibody assay result at 12 to 18 months of age. For both presumptive and definitive exclusion of infection, the child should have no other laboratory (e.g., no positive NAAT results) or clinical (e.g., no AIDS-defining conditions) evidence of HIV infection. for infants who have been breastfed, a similar testing algorithm can be followed, with additional testing every 3 months during breastfeeding followed by monitoring at 4 to 6 weeks, and 6 months after breastfeeding cessation. In the unusual case of an infant with a positive HIV NAAT result followed by a negative NAAT result, an expert in the care of children with HIV infection can be consulted for further testing recommendations. Intrapartum Continuation of Antenatal Antiretroviral DrugsART is recommended for the treatment of HIV and prevention of perinatal HIV transmission in all pregnant people with HIV, regardless of CD4 lymphocyte cell count and HIV RNA (viral load). Pregnant people should continue their antepartum antiretroviral (ARV) regimen on schedule during the intrapartum period to maintain maximal virologic suppression and to minimize the chance of developing drug resistance. When cesarean delivery is planned, oral medications can be administered preoperatively with sips of water. Medications that must be taken with food for absorption can be taken with liquid dietary supplements, contingent on consultation with the anesthesiologists during the preoperative period. If the maternal ARV drug regimen must be interrupted temporarily (i.e., for <24 hours) during the peripartum period, all drugs should be stopped and reinstituted simultaneously to minimize the chance that resistance will develop (19). Decision Regarding the Use of Intrapartum IV ZidovudineIntrapartum administration of IV Zidovudine (ZDV) provides antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis at a time when infants are at increased risk of exposure to maternal blood and body fluids. IV ZDV also is recommended for those with an initial diagnosis of HIV during labor and pregnant people with HIV whose HIV RNA level is unknown. Current evidence indicates that intrapartum IV ZDV reduces perinatal HIV transmission for people with HIV RNA>1,000 copies/mL who are on ART, but the benefits for those with HIV RNA <1,000 copies/mL are less clear. Based on available data, the recommendation is that IV ZDV should continue to be administered to pregnant people with HIV RNA >1,000 copies/mL within 4 weeks of delivery (or to people with HIV who have unknown HIV RNA levels within 4 weeks of delivery, regardless of their antepartum ARV regimen (20). IV ZDV is not required for individuals who meet all of the following 3 criteria (21):

If a patient has known or suspected ZDV resistance, intrapartum use of IV ZDV still is recommended in patient with HIV RNA>1,000 copies/mL near delivery unless a documented history of hypersensitivity exists. This intrapartum use of IV ZDV is recommended because of its proven record in reducing the risk of perinatal HIV transmission, even in the presence of maternal resistance to the drug (22). Dosage of IV Zidovudine (ZDV)Intrapartum IV ZDV is recommended for individuals with HIV RNA >1,000 copies/mL or unknown HIV RNA near the time of delivery or when they present in labor. In those with HIV RNA >1,000 copies/mL who are undergoing a scheduled cesarean delivery for prevention of perinatal HIV transmission, IV ZDV administration should begin at least 3 hours before the scheduled cesarean delivery; pregnant people should receive a 1-hour loading dose of ZDV at 2 mg/kg followed by a continuous IV ZDV infusion of 1 mg/kg for 2 hours (minimum of 3 hours total). This recommendation is based on a pharmacokinetic (PK) study in which ZDV was administered orally during pregnancy and as a continuous infusion during labor. Maternal ZDV levels were measure at baseline, after the initial IV loading dose, and then every 3 to 4 hours until delivery. ZDV levels were also measured in cord blood (23). When an urgent unscheduled cesarean delivery is indicated in a patient who has a viral load >1,000 copies/mL, considerations can be given to shortening the interval between initial of IV ZDV administration and delivery. When IV ZDV is not available, substitution of single-agent oral ZDV for IV ZDV is not recommended. Breastfeeding and Pre-masticationPeople with HIV should be encouraged to avoid breastfeeding (24). Monitoring of infants born to people with HIV who opt to breastfeed after comprehensive counselling should include immediate HIV diagnostic virologic testing with a NAT at the following time points: birth, 14 to 21 days, 1 to 2 months, and 4 to 6 months (25). Many experts then recommend testing every 3 months throughout breastfeeding, followed by monitoring at 4 to 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after cessation of breastfeeding. Clinicians caring for a person with HIV who is considering breastfeeding should consult with an expert, and if necessary, the Perinatal HIV Hotline (1-888-448-8765). For more information see: Pre-mastication: Receipt of solid food that has been pre-masticated or prewarmed (in the mouth) by a caregiver with perinatal HIV exposure aged <24 months with prior negative virologic tests, it will be necessary for such children to undergo virologic diagnostic testing because they may have residual maternal HIV antibodies (26). In addition to maintaining viral suppression in the breastfeeding parent, HIV prophylaxis should be considered for the infant. It is standard of care for all infants born to an individual living with HIV to receive 4 to 6 weeks of ARV prophylaxis with ZDV. The choice of agent and the length of therapy is dependent of the level of perinatal HIV risk (i.e., whether or not the individual was adherent to their ART regimen and virally suppressed during pregnancy and at the time of delivery). For infants with low risk of HIV transmission because the individual was virally suppressed, 4 weeks of ZDV is considered adequate prophylaxis. Infants who are at high risk of HIV transmission typically receive a combination ART regimen, usually ZDV, lamivudine, and nevirapine, in doses consistent with fully therapy (27). In the setting of a breastfed HIV-exposed infant, there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate additional benefit with a longer duration of neonatal chemoprophylaxis in infants of a parent who has chosen to breastfeed and are adherent to an ART regimen. This was illustrated in the HIV-1 infection prevention for postnatal HIV-1 transmission (HPTN 046) trial, which showed no difference in rates of perinatal HIV transmission among infants who received an additional 6 months of nevirapine as long the infant's breastfeeding parent was on an ART regimen (27). Nonetheless, some experts advocate to continue infant ARV prophylaxis throughout the duration of breastfeeding plus an additional 1-4 weeks. With effective parental ART, postnatal HIV transmission can be reduced to 0.3% (27). SummarySummary of American Academy of Pediatrics' (AAP's) Recommendations regarding diagnosis of HIV infection in infants and children are:

Suggested Reading

References

|