Доброкачественные кожные заболевания вульвы: Часть 1

WHEC практики Бюллетень и клинических управления Руководство для медицинских работников. Образования гранта, предоставленного здоровья женщин-образовательный центр (WHEC).

Nearly one in six women will experience chronic vulvar symptoms at some point, from ongoing itching to sensations of rawness, burning, or dyspareunia. Regrettably, clinicians generally are taught only a few possible causes for these symptoms, primarily infections such as yeast, bacterial vaginosis, herpes simplex virus, or anogenital warts. However, infections rarely produce chronic symptoms that do not respond, at least temporarily, to therapy. In this series we focus on non-malignant disorders of vulvar skin. In many chronic cases, more than one entity is the cause. Specific skin diseases, sensations of rawness from various external and internal irritants, neuropathy, and psychological issues are all much more common causes of chronic vulvar symptoms than infections. Moreover, most women with chronic vulvar symptoms have more than one entity producing their discomfort. Very often, the cause of a patientís symptoms is not clear at first visit, with non-specific redness or even normal skin seen on examination. Pathognomonic skin findings can be obscured by irritant contact dermatitis caused by unnecessary medications or over-washing, atrophic vaginitis, and/or rubbing and scratching. In such cases, obvious abnormalities must be eliminated and the patient re-evaluated to definitely discover and treat the causes of the symptoms. Vulvar skin disorders can interfere with sexual function because of discomfort, pain, and embarrassment. Chronic vulvar conditions impact not only a womanís sexual well-being but also her overall quality of life (1). As women become more comfortable with vulvar health, they will seek the advice of their healthcare providers, especially about their sexual health. Gynecologist must be prepared to diagnose and treat vulvar conditions, including chronic vulvar skin disorders.

The purpose of this document is to review diagnostic approaches and provide a structured framework for the management of common vulvar disorders. Symptoms of vulvovaginal disorders are common, often chronic, can significantly interfere with womenís sexual function and sense of well-being. In the evaluation of women who report symptoms of vulvar disorders, the most common diagnoses are dermatologic conditions and vulvodynia (both generalized and localized forms). Vulvar pain and dyspareunia are common presenting complaints in the office setting. Vulvar dermatoses must be considered as a part of the differential diagnosis for any woman with sexual dysfunction or pain. A detailed history and physical examination, backed by a confident knowledge of the vulvar dermatoses, will aid in diagnosis and treatment. Focus of this review is on common benign conditions of vulvar skin: contact dermatitis; lichnoid vulvar dermatoses; extramammary Pagetís disease and squamous cell hyperplasia: their diagnosis and current management.

BACKGROUND

Pruritus and pain are two most common presenting symptoms of vulvar disorders in women treated in clinics that provide specialized care for vulvar conditions (2). Pruritus and vulvar pain may occur in the presence of obvious dermatologic disease or in conditions with few visible skin changes. In evaluating vulvar pruritus, it can be helpful to identify women into those with acute symptoms and those with chronic symptoms. Vulvodynia, defined as burning, stinging, rawness, or soreness, with or without pruritus, can be further characterized by the site of the pain, whether it is generalized or localized, and whether it is provoked, spontaneous, or both (3).

EXAMINATION & EVALUATION

A comprehensive history and physical examination are essential in the management of vulvar conditions. A full sexual history, including current sexual practices and infections, is crucial. Eliciting use of topical or over-the-counter medications is important. A history of genital surgery, including labiaplasty, which is becoming much more common, should also be noted. It is also important to ask about vulvar trauma. Lastly, exercise regimens and vulvovaginal care habits should be discussed. Examination of the vulva should be systematic and thorough, performed in dorsal lithotomy position with proper lighting. A mirror might be helpful to allow the patient to communicate the location of concern. Observation of the vulva includes identification of atrophy, erythema, induration, fissures, lichenification, ulceration, erosions, changes in pigmentation, and scarring. A cotton swab may be used to detect tenderness or decreased sensation. Examination with a colposcope can be very useful, and we highly recommend its use. A speculum examination is necessary to detect vaginal findings such as ulceration, synechiae, loss of rugae, pallor, and petechiae. Vaginal discharge should be obtained for cultures, wet mount, and pH assessment. Abnormalities warrant a vulvar biopsy; many vulvar dermatologic conditions cannot be diagnosed by mere observation. A general examination, including skin, eyes, and mouth, should be performed as some vulvar dermatoses are associated with autoimmune conditions and extra-genital lesions. A systematic approach to physical examination is essential when considering the differential diagnosis of vulvar presentations.

Conditions Commonly Associated with Vulvar Pruritus

Acute:

- Infections Ė fungal, including candidiasis and tinea cruris, trichomoniasis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, molluscum contagiosum, infestations including scabies and pediculosis;

- Contact dermatitis (allergic or irritant).

Chronic:

- Dermatoses Ė atopic and contact dermatitis; lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, lichen simplex chronicus; psoriasis; genital atrophy;

- Neoplasia Ė vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), vulvar cancer and extramammary Pagetís disease;

- Infection Ė human papillomavirus (HPV) infection;

- Vulvar manifestations of systemic disease Ė Crohn disease.

2011 International Society for the Study of Vulvar Disease (ISSVD) Terminology and Classification of Vulvar Dermatological Disorders:

"Dystrophy" is no longer an acceptable term; the new ISSVD classification system lists specific dermatologic disorders (24).

1) SKIN-COLORED LESIONS

A. Skin-colored papules and nodules

- Papillomatosis of the vestibule and medial labia minora (a normal finding; not a disease)

- Molluscum contagiosum

- Warts (HPV infection)

- Scar

- Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

- Skin tag (acrochordon, fibroepithelial polyp)

- Nevus (intradermal type)

- Mucinous cysts of the vestibule and medial labia minora (may have yellow hue)

- Epidermal cysts (Syn, epidermoid cyst; epithelial cyst)

- Mammary-like gland tumor (hidradenoma papilliferum)

- Bartholin gland cyst and tumor

- Syringoma

- Basal cell carcinoma

B. Skin-colored plaques

- Lichen Simplex chronicus and other lichenified disease

- Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

2) RED LESIONS: PATCHES AND PLAQUES

A. Eczematous & lichenified diseases

- Allergic contact dermatitis

- Irritant contact dermatitis

- Atopic dermatitis (rarely seen as a vulvar presentation)

- Eczematous changes superimposed on other vulvar disorders

- Diseases clinically mimicking eczematous disease (candidiasis, Hailey-Hailey disease and extramammary Pagetís disease)

- Lichen simplex chronicus (lichenification with no preceding skin lesion)

- Lichenification superimposed on an underlying preceding pruritic disease

B. Red patches & plaques (no epithelial disruption)

- Candidiasis

- Psoriasis

- Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

- Lichen planus

- Plasma cell (Zoonís) vulvitis

- Bacterial soft-tissue infection (cellulitis and early necrotizing fasciitis)

- Extramammary Pagetís disease

3) RED LESIONS: PAPULES AND NODULES

A. Red papules

- Folliculitis

- Wart (HPV infection)

- Angiokeratoma

- Molluscum contagiosum (inflamed)

- Hidradenitis suppurativa (early lesion)

- Hailey-Hailey disease

B. Red nodules

- Furuncles (boils)

- Wart (HPV infection)

- Prurigo nodularis

- Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

- Molluscum contagiosum (inflamed)

- Urethral caruncle and prolapse

- Hidradenitis suppurativa

- Mammary-like gland adenoma (hidradenoma papilliferum)

- Inflamed epidermal cyst

- Bartholin duct abscess

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Melanoma (amelanotic type)

4) WHITE LESIONS

A. White papules and nodules

- Fordyce spots (a normal finding; may sometimes have a yellow hue)

- Molluscum contagiosum

- Wart

- Scar

- Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Milium (pl. milia)

- Epidermal cyst

- Hailey-Hailey disease

B. White patches and plaques

- Vitiligo

- Lichen sclerosus

- Post-inflammatory hypopigmentation

- Lichenified diseases (when the surface is moist)

- Lichen planus

- Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

- Squamous cell carcinoma

5) DARK COLORED (BROWN, BLUE, GRAY or BLACK) LESIONS

A. Dark colored patches

- Melanocytic nevus

- Vulvar melanosis (vulvar lentiginosis)

- Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation

- Lichen planus

- Acanthosis nigricans

- Melanoma-in-situ

B. Dark colored papules and nodules

- Melanocytic nevus (includes those with clinical and/or histologic atypia)

- Warts (HPV infection)

- Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

- Seborrheic Keratosis

- Angiokeratoma (capillary angioma, cherry angioma)

- Mammary-like gland adenoma (hidradenoma papilliferum)

- Melanoma

6) BLISTERS

A. Vesicles and bullae

- Herpes virus infections (herpes simplex, herpes zoster)

- Acute eczema

- Bullous lichen sclerosus

- Lymphangioma circumscriptum (lymphangiectasia)

- Immune blistering disorders cicatricial pemphigoid, fixed drug eruption, Steven-Johnson syndrome, pemphigus)

B. Pustules

- Candidiasis (candidosis)

- Folliculitis

7) EROSIONS AND ULCERS

A. Erosions

- Excoriations

- Erosive lichen planus

- Fissures arising on normal tissue (idiopathic, intercourse related)

- Fissures arising on abnormal tissue (candidiasis, lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, Crohnís disease, etc.)

- Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), eroded variant

- Ruptured vesicles, bullae and pustules

- Extramammary Pagetís disease

B. Ulcers

- Excoriations (related to eczema, lichen simplex chronicus)

- Aphthous ulcers; syn. Aphthous minor, aphthous major, LipschŁtz ulcer occurring either as an idiopathic process or secondary to other diseases such as Crohnís, Behҫetís, various viral infections)

- Crohnís disease

- Herpes-virus infection (particularly in immunosuppressed patients

- Ulcerated squamous cell carcinoma

- Primary syphilis (chancre)

8) EDEMA (DIFFUSE GENITAL SWELLING)

A. Skin-colored edema

- Crohnís disease

- Idiopathic lymphatic abnormalities (congenital Milroyís disease)

- Post-radiation and post-surgical lymphatic obstruction

- Post-infectious edema (esp. staphylococcal and streptococcal cellulitis)

- Post-inflammatory edema (esp. hidradenitis suppurativa)

B. Pink or red edema

- Venous obstruction (e.g. pregnancy, parturition)

- Cellulitis (primary or super-imposed on already existing edema)

- Inflamed Bartholin duct cyst/abscess

- Crohnís disease

- Mild vulvar edema may occur with any inflammatory vulvar disease

IRRITANT AND CONTACT DERMATITIS

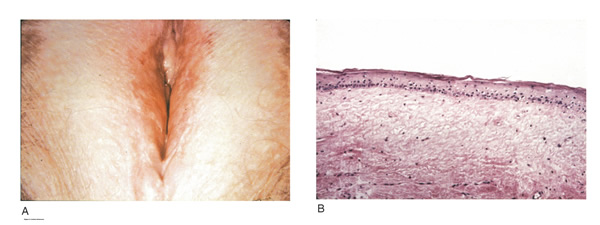

Contact dermatitis is one of the most common and often avoidable problems. The incidence is approximately 15% to 30%; however, with increased use of over-the-counter vulvar products, the incidence is rising (4). Exogenous agents cause inflammation of the skin. Common irritants and allergens include body fluids, menstrual pads, heat, soaps and detergents, antibiotics, douches, fragrances, nickel (from piercing), rubber, and spermicides (5). In addition, semen can also act as an irritant or allergen. Clinical examination may reveal a range of findings from mild erythema and swelling to severe erythema, fissures, skin thickening, erosion, and ulceration (see figure 1 below). A detailed history and physical examination are keys to diagnosis; however, physicians should have a low threshold for biopsy to rule out coexisting conditions. With continued exposure or chronic scratching, lichen simplex chronicus may develop.

Figure 1: Contact dermatitis occurs when an irritant or allergen causes inflammation, presenting clinically in a range from mild erythema and swelling to severe erythema, fissures, skin thickening, erosion, and ulceration.

Identification and removal of the causative agent is the main goal of treatment. It is essential to counsel patients on proper vulvar hygiene. Inflammation may be alleviated with topical steroids, including triamcinolone 0.1% ointment twice daily for moderate cases and clobetasol 0.05% ointment once daily for severe cases. Ice packs and antihistamines, such as hydroxyzine, are helpful for vulvar pruritus. Scratching during sleep can be especially difficult to treat. Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants, such as hydroxyzine are helpful for vulvar pruritus. Scratching during sleep can be difficult to treat. Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, may be given at bed-time for this purpose. Patients should be examined 1 month after initiating treatment, with steroids and antidepressants tapered with resolution of symptoms. Superimposed fungal and bacterial infections are common and should be treated. Patients who do not respond to treatment will need reevaluation and a biopsy to exclude other conditions.

The following vulvar care measures can minimize vulvar irritation and/or vulvar pain:

- Wear 100% cotton underwear (no underwear at night);

- Avoiding vulvar irritants (perfumes, dyes, shampoos, and detergents) and douching; using mild soaps for bathing, with none applied to vulva, cleaning the vulva with water only;

- Avoiding the use of hair dryers on the vulvar area;

- Patting the area dry after bathing, and applying a preservative-free emollient (such as vegetable oil or plain petroleum) topically to hold moisture in the skin and improve the barrier function;

- Switching to 100% cotton menstrual pads (if regular pads are irritating);

- Using adequate lubrication for intercourse;

- Applying cool gel packs to the vulvar area;

- Rinsing and patting dry the vulva after urination.

LICHNOID VULVAR DERMATOSES

The more common vulvar dermatoses include ďthe three lichensĒ: lichen simplex chronicus, lichen sclerosus (LS), and lichen planus (LP). Although they are discussed separately in this chapter, they may coexist simultaneously.

Lichen Simplex Chronicus

Lichen simplex chronicus is also known as squamous hyperplasia. It represents an end-stage disorder resulting from long-standing irritation, endogenous eczema, allergens, or infection (6). Patients often present with intractable itching and pruritus. The pruritus is often worse at night, and chronic scratching may lead to lichenification, fissures, and post-inflammatory pigment changes. The vulvar surface in lichen simplex chronicus has a leathery appearance, and the cutaneous markings are quite pronounced. A biopsy is often necessary to exclude lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, or vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (7). It affects quality of life, impacting both psychological and sexual well-being. The condition has been associated with psychological problems, including demoralization, depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and sleep disturbances. Compared to matched controls, women with lichen simplex chronicus demonstrated significantly lower scores on the Female Sexual Function Index, especially in the domain scores of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and sexual satisfaction (8).

Figure 2: Lichen simplex chronicus is a chronic eczematous condition characterized by intense and unrelenting pruritis, leading to scratching and lichenification

Management: identifying and eliminating all irritant and allergen exposure is the first step in treatment of lichen simplex chronicus. It is also essential to break the itch-scratch-itch cycle, which can be difficult as women may scratch in their sleep. Night-time pruritus may be alleviated with oral amitriptyline at bedtime and application of ice. Inflammation may be treated with topical application of high potency corticosteroids. Concomitant infections should be treated accordingly.

Lichen Sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus, a chronic disorder of the skin, is most commonly seen on the vulva, with extragenital lesions reported in up to 13% of women with vulvar disease. It affects approximately 1 in 70 women, usually presenting in premenarchal girls and menopausal women (7). The mean age of onset is in the fifth to sixth decade, but it may occur at any age, including prepuberty (9). The exact etiology of this condition is unclear, although an autoimmune process or possible genetic link is likely (9),(10). Patients presenting with lichen sclerosus most commonly report pruritus, followed by irritation, burning, dyspareunia, and tearing. The prevalence of this condition remains unknown because lichen sclerosus may be asymptomatic. There is a 5% associated risk of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma, and it is unclear if treatment decreases this risk (11).

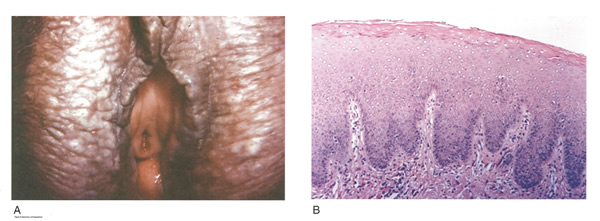

Chronic vulvar pain has been reported by 79% of women with lichen sclerosus (7). Of all quality of life domains, sexual function is most impacted. Lichen sclerosus can cause sexual dysfunction, with introital dyspareunia and decreased sexual activity. This disorder has been shown to cause sexual distress by affecting desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain (12). However, treatment of lichen sclerosus does improve sexual dysfunction (13). Physical examination reveals ivory white atrophic plaques with a ďcigarette paperĒ appearance. Although vulvar lichen sclerosus can be a clinical diagnosis, skin changes may be difficult to differentiate from vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, and a biopsy should be performed before treatment with topical steroid is initiated. Although the vaginal epithelium is largely spared from lichen sclerosus, involvement of the mucocutaneous junctions may lead to introital narrowing. Perianal involvement can create the classic ďfigure of eightĒ or hourglass shape. Other findings include fusion of the labia minora, phimosis of the clitoral hood, and fissures (14).

Figure 3: Lichen Sclerosus (A) the vulva appears whitened, and the labia minora are obliterated; (B) histologic criteria for lichen sclerosus include a thin epithelium with a decreased number of cell layers and loss of the underlying rete ridges.

Management: First-line treatment is clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment applied once daily at night for 4 weeks, followed by alternate night for 4 weeks, then twice weekly for 4 weeks. Patients should follow up 2 to 3 months after initiating treatment, followed by 6 months, and then seen annually if disease is well controlled (11). Approximately 60% of patients will experience complete remission of their symptoms with this regimen (15). The topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have been studied, but given their unclear long-term safety profiles, they are not considered first-line treatment (16).

Role of estrogen and testosterone cream in the management

The use of estrogen treatment of vaginal atrophy has been well documented and can be accomplished with the variety of locally applied estrogen preparations (17). However, some differences have been demonstrated between forms of local therapies. When compared in randomized controlled trials with either estrogen tablets or with the estrogen ring, conjugated equine estrogen cream was found to be significantly associated with adverse effects, including bleeding, breast pain, and perineal pain (18). All forms of topical estrogen therapy increase the possibility of endometrial hyperplasia and overstimulation. However, it is currently unknown whether women receiving long-term therapy with topical estrogen require prophylactic therapy with progesterone. It should be noted that systemic estrogen therapy, although efficacious, raises concerns for many women and may still not be sufficient to relieve the symptoms of urogenital atrophy. Whether or not estrogen use improves the function of vulvar epithelium in vulvar atrophy (including clitoral circulation and fibrosis) remains controversial. Small studies have demonstrated improvement in circulation and sexual function in women following localized or systemic estrogen use (19). Topical estrogen therapy also has been reported for the treatment of symptomatic labial adhesions. The use of estrogen for other vaginal disorders is less well documented, and includes treatment for radiation injury and treatment of vaginal mucosa burn injury following misapplication of 100% acetic acid.

Indications for the use of testosterone cream in the treatment of vulvar or vaginal disorders remain controversial. However, testosterone cream was used in the treatment of lichen sclerosus. Subsequently, studies were undertaken comparing testosterone with topical steroids in the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus and resulted in two findings, a lack of clear effect with testosterone and the superiority of topical steroids. Thus, given the undesirable side effects of masculinization and virilization associated with the use of testosterone, and unproven therapeutic benefit, it should not be used in the primary treatment of lichen sclerosis (20).

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus, an autoimmune inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder, affects approximately 1% of women with a peak incidence from age 30 to 60 years (16). Patients may present with pruritis, burning, dyspareunia, postcoital bleeding, or vaginal discharge. This disease severely affects sexual interaction. Nearly 8% of women examined for evaluation of vulvar pain were found to have lichen planus. 95% of women reported sexual dysfunction, with dyspareunia in 60% and apareunia in 35% of women (21). Erosive lichen planus presents as glassy, brightly erythematous erosions accompanied by white striae (Wickhamís striae). The disease may markedly alter the vulvovaginal anatomy resulting in loss of labia minora, narrowing of the introitus, and obliteration of the vagina. Patients frequently report a copious yellow vaginal discharge. Lichen planus can be misdiagnosed as lichen sclerosus. Unlike lichen planus, lichen sclerosus has a waxy or ďcigarette paperĒ appearance and rarely displays vaginal involvement. It is important to remember that lichen sclerosus and lichen planus may coexist in the same patient.

Figure 4: Lichen planus is an autoimmune inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder targeting oral and vulvovaginal mucosa. Erosive lichen planus presents as glassy, brightly erythematous erosions accompanied by white striae (Wickhamís striae). Loss of labia minora, narrowing of the introitus, and obliteration of the vagina occur with disease progression.

Vulvar and vaginal lichen planus are difficult to treat; lesions are relatively resistant to available therapies. First line treatment is topical clobetasol propionate 0.05%. Daily treatment should be continued until lesions have resolved and then slowly tapered, with a limit of 3 months. Soaking in warm water may aid in penetration of the topical through heavily keratinized lesions (21). Vaginal lichen planus may be treated with intra-vaginal hydrocortisone suppositories to prevent obliteration of the vagina. Calcineurin inhibitors have also been used for vulvovaginal lichen planus with good success. When topical medications fail, the next step is systemic treatment with an oral corticosteroid, 40 to 60 mg per day for 2 to 4 weeks. Although not recommended for active lichen planus, in cases of severe scarring, surgery to lyse vulvovaginal adhesions may be necessary to restore a womanís sexual function (22).

VULVAR BIOPSY

The threshold for biopsy of the vulva should be low except in the pediatric population. Changes on the vulva often are subtle and can be overlooked. Findings such as thickening, pebbling, hypopigmentation, or thinning of the epithelium indicate a possible dermatologic process, and biopsy will aid in diagnosis and management. Biopsy of hyperpigmented or exophytic lesions, lesions with changes in vascular patterns, or unresolving lesions is particularly important and should be performed in order to rule out carcinoma. Diagnostic delays in identifying vulvar cancer are exceedingly common and have been linked to failures or procrastination in the performance of biopsies of abnormal-appearing vulvar skin.

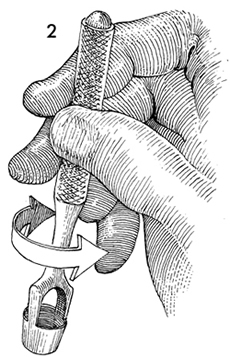

Figure 5: A Keys punch, commonly used by dermatologists, is excellent for this purpose. The 5-7 mm size allows appropriate pathologic specimens to be taken without leaving a defect large enough to require sutures .

One of the most common methods of biopsy involves the use of a 3Ė5-mm Keyes punch. A shave or snip biopsy works best for sampling more superficial disorders, such as lichen sclerosus or lichen planus, or for sampling bullous lesions. Although both shave and snip samples will extend into the dermis, they should not go through the dermis. A stitch or topical solution can be used to control bleeding (20).

Anesthesia is recommended for vulvar biopsy; combination lidocaine and prilocaine cream or 4% liposomal lidocaine cream can be placed on the proposed biopsy site before inserting the anesthesia needle. A systematic review of topical anesthetics for dermatologic procedures found both medications to be effective, but liposomal lidocaine had a more rapid onset (30 minutes versus 60 minutes with combination lidocaine and prilocaine cream) and lower cost. To minimize discomfort, a solution of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate can be added to the lidocaine (1:10 ratio). Onset of action occurs within 2Ė5 minutes; if epinephrine is used with either of these anesthetics, the onset of action will be delayed, but the duration of effect will be increased (26). Choice of biopsy instrument depends on the location and nature of the lesions. For most inflammatory diseases, ulcers, pigmented lesions, or suspected tumors, a punch biopsy is the preferred method because establishing the depth of such lesions is critical. Small lesions often can be completely excised, and lesions involving the submucosal or subcutaneous tissue should be adequately sampled. When sampling ulcerative areas, a biopsy of the edge of the ulcer is preferred; when sampling hyperpigmented areas, a biopsy of the thickest region is recommended.

SQUAMOUS CELL HYPERPLSIA (Acanthosis)

Squamous cell hyperplasia (formerly called hypertrophic dystrophy) is a chronic pruritic condition of unknown etiology that requires biopsy for diagnosis. The epithelium is thickened, and the gross appearance is highly variable, including elevated tissue areas, thickening, fissures, and excoriations. It is also characterized by white epithelium, which usually appears thickened with an irregular surface. The change may be unilateral and plaque-like or more diffuse; symmetry, as seen in lichen sclerosus, is rare. Shrinkage and agglutination of the labia are not seen, nor are the focal areas of ecchymosis found that may occur in lichen sclerosus. Biopsy reveals hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, lengthening and distortion of rete pegs, and parakeratosis. Squamous cell hyperplasia has been found in 25-35% of women with lichen sclerosus (27). The term squamous cell hyperplasia encompasses changes previously specified as hyperplastic dystrophy but should not be used if a specific dermatoses can be identified (e.g. psoriasis, lichen planus, condyloma acuminatum, lichen simplex chronicus). Epithelial changes secondary to chronic monilial or dermatophyte infection may give similar epithelial changes, and these must be excluded. Those cases demonstrating atypia with changes of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia are to be classified as VIN. The term ďhyperplastic dystrophy with atypiaĒ is not recommended; these cases should be placed in VIN category. The term ďmixed dystrophyĒ is no longer recommended because it is now appreciated that such cases reflect the spectrum of lichen sclerosus, which may present with adjacent or associated hyperplastic and hyperkeratotic areas.

Figure 6: Squamous cell hyperplasia; A. The lesion appears whitened and raised; B. Histologic criteria for squamous cell hyperplasia include a thickened acellular layer of surface keratin with deepened and broadened rete ridges (acanthosis).

Treatment is directed primarily at control of symptoms. Because pruritis is the usual complaint, steroids are the mainstay of therapy. Topical fluorinated compounds, such as Valisone, almost always control the pruritis. Regression of the lesion is usually evident within 4-6 weeks, and long-term corticosteroid therapy is not necessary and may be detrimental in that it can result in atrophic changes. Recurrence is uncommon. To prevent recurrence, it is important to exclude inciting agents such as residual laundry products in clothing or underwear fabrics that may be occlusive or irritating.

EXTRAMAMMARY PAGETíS DISEASE OF VULVA

In 1874 Sir James Paget described the mammary disease associated with his name. Although he suggested a similar disease in extramammary sites, the first pathologic description of extramammary Pagetís disease of the vulva was described by Dubreuilh in 1901. In contrast to mammary Pagetís disease, which is usually associated with an associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, vulvar Pagetís disease is associated with an underlying apocrine gland carcinoma in fewer than 25% of cases. Of note is the observation that vulvar Pagetís disease may be associated with carcinoma in extragenital area, such as the breast and gastrointestinal tract.

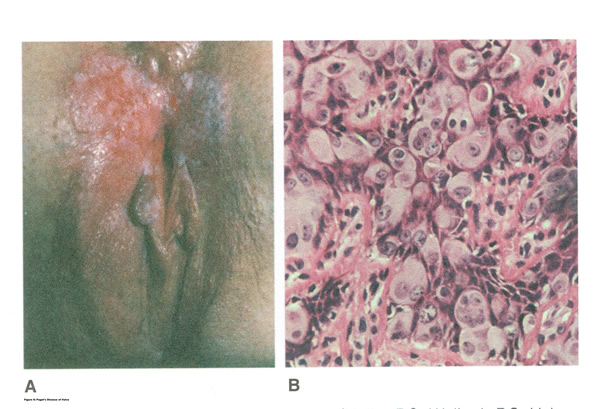

Vulvar Pagetís, or extramammary Pagetís, is a rare condition that often presents with itching, burning, or bleeding. It is a rare form of intraepithelial neoplasia characterized by adenocarcinomatous cells and accounts for approximately 2% of vulvar neoplasms. Although most cases of extramammary vulvar Pagetís disease are primary rather than associated with underlying adenocarcinoma, approximately 25% of cases are associated with neoplastic disease (20),(23). When associated disease is present, it is typically local (adenocarcinoma in the skin adnexal or Bartholin gland) but also may be distant most commonly, of the breast, but also perianal extramammary Pagetís disease is associated with underlying colorectal adenocarcinoma in up to 80% of cases (23). Thus, when Pagetís disease is confirmed by biopsy, evaluation including breast, genitourinary tract, and gastrointestinal tract should be undertaken.

Figure 7: A. Pagetís disease of vulva; B. Histopathology of Pagetís disease.

The typical patient with vulvar Pagetís disease is in her mid-60s and has delayed for 1 to 2 years seeking medical assistance for a pruritic, inflamed vulva. A diagnosis of candidiasis may be made, and the patient will be treated with antifungal agents. There will be no resolution of symptoms. Subsequent examination of the vulva reveals no change in the rather diffuse white epithelium with interspersed islands of erythema (see picture above). Although candidiasis and Pagetís disease have similar clinical appearances, the hyperkeratosis associated with Pagetís disease appears much thicker. Candidal infections tend to be more diffuse than Pagetís disease. Occasionally infections tend to be more diffuse than Pagetís disease. Occasionally, the patient with Pagetís disease may be seen with a lesion that resembles eczema with its scaly surface. A biopsy to establish appropriate diagnosis is mandatory. Histopathologic examination demonstrates the characteristic intraepithelial Pagetís cells, which have large, prominent nucleoli and pale, abundant, basophilic and finely granular cytoplasm. These cells tend to form intraepithelial clusters or gland-like nests. Cytoplasmic staining with mucicarmine, aldehyde fuchsin, and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) can be seen in most cases. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) demonstrable by immunoperoxide technique is characteristic. Although they may seen at various levels in the epidermis, they are most frequently concentrated in the lower regions. Apocrine glands and hair shaft epithelium infiltrated by Pagetís cells should not be interpreted as invasion; underlying adenocarcinoma of sweat gland, Bartholinís gland, or invasion by overlying Pagetís disease may be found.

The origin of these cells is controversial. Extramammary Pagetís disease is located only in sites containing apocrine glands such as the anal-genital and axillary regions. Pagetís cells bear a greater resemblance to glandular cells than to squamous cells, although Cytoplasmic organelles are present, which are consistent with both squamous and secretory skin cells. Pagetís cells are frequently arranged in glandular patterns. Histochemical staining of Pagetís cells demonstrates enzymes typically found in apocrine gland cells. CEA has been noted in Pagetís cells, sweat glands, and underlying adenocarcinoma but not in squamous epithelium, hair follicles, or sebaceous glands. Pagetís cells represent a population of cells sharing features of glandular epithelium and arise within the epidermis. Their origin may be from an undifferentiated epithelia stem cell. The occurrence of Pagetís disease in the ďmilk lineĒ suggests that mammary and extramammary Pagetís cells are embryologically similar, a notation supported by the fact that cells in the vulva show the same phenotype as those in the breast. The histologic confirmation of Pagetís disease should be prompt a complete evaluation of the lower reproductive tract for evidence of disease. The urethra, bladder, ureter, vagina, and cervix have been noted to be involved with this disease process. Although involvement with structures other than the vulva is uncommon, a mammogram and gastrointestinal survey should be obtained to rule out concomitant adenocarcinoma in these areas.

Extramammary Paget disease has been classified into several subtypes (25):- Type 1a primary cutaneous extramammary Pagetís disease arises from apocrine glands within the epidermis (in situ) or underlying skin appendages;

- Type 1b primary cutaneous extramammary Pagetís disease (15-25%) is associated with invasive Pagetís disease or adenocarcinoma in situ;

- Type 2 extramammary Pagetís disease originates from underlying anal or rectal adenocarcinoma;

- Type 3 extramammary Pagetís disease originates from bladder adenocarcinoma

Management of Extramammary Pagetís Disease

The therapy of Pagetís disease involves a carefully planned surgical approach. Pagetís cells may spread horizontally as well as vertically and may be found in normal-appearing skin. The mere excision of abnormal appearing skin from the vulva of the patient with Pagetís disease is therefore suboptimal. Careful attention should be given to surgical margins. These are optimally evaluated by frozen section in the operating suite. If margins are involved with Pagetís cells, further excision and evaluation are warranted before termination of the procedure. Not only should excisions be wide, but they should also be deep to incorporate all adnexal that may contain Pagetís cells or underlying adenocarcinoma. With diffuse disease, a total vulvectomy is necessary.

Patients with Pagetís disease involving the anus usually have an associated adenocarcinoma of the rectum, requiring and abdomino-perineal resection. The finding of adenocarcinoma in the biopsy specimen from the patient with Pagetís disease warrants a total vulvectomy with bilateral inguinal-femoral groin node dissections. Skinning vulvectomy, laser ablation, cryotherapy, partial excision, and chemotherapy, which are frequently used to treat patients with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), are suboptimal in the treatment of primary Pagetís disease. These more conservative procedures are of value in the treatment of residual or recurrent disease once underlying adenocarcinoma has been excluded. Destruction of the vulvar skin without proper evaluation for an underlying adenocarcinoma is inappropriate. Likewise, superficial excision without appropriate assessment of the deep adnexal structures will result in either recurrence of disease or the delayed observation that an adenocarcinoma is present. Recurrence is common (30-50%), so patients should be re-examined every 3 months after surgery for the next 2 years, after which annual follow-ups are recommended. Recurrence generally leads to further surgery (25).

Faced with a high recurrence rate and often mutilating surgical procedures, margin status gained interest. High recurrence rates have been attributed to subclinical extension and multifocal disease. Perioperative identification of margins was attempted with the use of frozen sections or fluorescein. Intraoperative frozen section studies revealed high rates of false-negative margins (approaching 40%, limited use in the presence of multicentric disease, as well as little effect on disease outcome (28). Routine frozen sections, by processing technique, sample only 0.1% of the surgical margin. Several adjuvant techniques have been studied to help uncover the extent of tumor spread and precise location of disease. Multiple scouting biopsies have been advocated and reported by several investigators using various techniques. Preoperative knowledge of lesion size and extent provides for better preparatory surgical and reconstructive planning, but requires additional interventions and delays time to surgery. Despite this, tumor-free margins cannot be established with certainty because of the occurrence of false-negative biopsies, often stemming from sampling errors or simply from the multifocal nature of extramammary Pagetís disease.

Laser treatment gained interest in the hopes that it would provide a conservative approach to eradicate the disease while preserving vulvar anatomy and sexual function. Already used to treat vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, several surgeons began exploring this option to treat vulvar intraepithelial Pagetís disease. CO2 and Nd: YAG lasers have been reported useful in the treatment. Though operative and hospitalization times are shorter, the procedures can be quite painful for a considerable period of time, prompting certain patients to defer a subsequent treatment. Another major drawback is the lack of histologic evidence for noninvasive disease or clear surgical margins. Whereas some investigators reported success with laser treatment, several reports noted significant recurrence after the use of laser surgery in this condition (29). Reasons for high recurrence rates (reaching up to 67%) after a 2-year follow up included the use of laser therapy in more extensive lesions, multifocal origin of the disease, and perhaps an overly superficial ablation by laser (up to the reticular dermis in all studies) when compared with surgical removal. Photodynamic therapy can be considered a useful option especially when treating patients with inoperable patients or extramammary Pagetís disease in difficult anatomic locations.

Less aggressive measures using topical therapies have long been considered and attempted in the management with extramammary Pagetís disease. In particular, various treatment regimens using 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) have been tried over the last several years, mostly in combination therapy, before surgery or after surgery, to evaluate residual disease and rarely as a single agent. Its use as an adjunct before surgery intervention has been proved useful but could not completely delineate extramammary Pagetís disease margins as was proven after pathologic review. Imiquimod cream, a low-molecular-weight imidazoquinoline amine, has shown some interesting results and multiple case reports have surfaced over the course of last decade detailing various treatment regimens. Most patients were treated thrice weekly for an average of 3 months. In most studies with imiquimod 5% cream, biopsies were done immediately after treatment and several months later with both clinical and pathologic clearance of extramammary Pagetís disease frequently reported. These results contrast with the 5-FU response, where clinical resolution was noted without pathologic cure (30).

This biologic response modifier enhances both innate and acquired immune function and is known to stimulate cytokines, specifically interferon-alpha (IFN-α) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), at the site of application. Response to treatment would seem to go beyond a simple destructive effect by actually stimulating a specific immune response to tumor cells. Side effects reported with treatment range from effects reported with treatment range from moderate-to-severe local irritation to flu-like symptoms, nausea and vomiting. Imiquimod can be considered an alternative to surgery, an adjunct before or after surgery, and even part of a therapeutic combination with other treatment modalities (31). Though only case reports or case series have been published thus far, results seem promising.

Topical bleomycin has also been attempted in the treatment of vulvar extramammary Pagetís disease. In this study, four cases were treated with topical bleomycin 3.5% in an ointment base twice daily for 2 weeks with a rest period of 4 to 6 weeks and a maximum of four cycles. All achieved complete clinical remission of the disease but one patient experienced a recurrence 30 months later requiring retreatment with a single course of topical bleomycin. Side effects were limited to treated areas (31).

Case reports case series on the use of radiotherapy in extramammary Pagetís disease have surfaced with interesting results. Used as an initial treatment mostly in selected patient groups (i.e. the elderly or those unfit to undergo conventional surgery), cases of large lesions or located in functionally delicate anatomic areas for surgery, radiotherapy has also been reported in combination with surgery or following a recurrence. Described treatment techniques, including beam type, beam energy, and total doses, differ between publications. Initial reports suggested a high recurrence rate, whereas later ones seem to present more encouraging results (32). Acute and chronic radiation toxicity can occur. Randomized controlled trials are needed to adequately evaluate lymph node involvement and compare various therapeutic strategies, so that standardization may be attempted and initial treatment protocols elaborated to determine the best combination of greatest efficacy with least morbidity.

CONCLUSION

Vulvar pain, itching and dyspareunia are common presenting complaints in the office setting. Vulvar dermatoses must be considered as a part of the differential diagnosis for any woman with sexual dysfunction or pain. A detailed history and physical examination, backed by a confident knowledge of the vulvar dermatoses, will aid in diagnosis and treatment. Symptoms of vulvar lesions include pruritis, soreness, dyspareunia, and shrinkage of the introitus, but are non-specific. Biopsies of vulvar lesions, especially from sites of fissuring, ulceration, induration, or thick plaques, are recommended before treatment. Topical estrogen cream helps reverse atrophic vulvovaginal changes resulting from estrogen deficiency but is not helpful for lichen sclerosus. A wide local excision would not be necessary unless malignancy is suspected on the initial biopsy. The recommended treatment for lichen sclerosus is an ultra-potent topical corticosteroid, such as clobetasol propionate. Biopsy of hyperpigmented or exophytic lesions, lesions with changes in vascular patterns, or unresolving lesions is particularly important and should be performed to rule out carcinoma. For patients with biopsy confirmed Pagetís disease, further evaluation of the breast, genitourinary tract, and gastrointestinal tract should be undertaken.

References

- Ermertcan AT, Gencoglan G, Temeltras G, et al. Sexual dysfunction in female patients with neurodermatitis. J Androl 2011;32(2):165-169

- Hansen A, Carr K, Jensen JT. Characteristics and initial diagnoses in women presenting to a referral center for vulvovaginal disorders in 1996-2000. J Reprod Med 2002;47:854-860. (Level III)

- Moyal-Barracco M, Lynch PJ. 2003 ISSVD terminology and classification of vulvodynia: a historical perspective. J Reprod Med 2004;49:772-777. (Level III)

- Beecker J. Therapeutic principles in vulvovaginal dermatology. Dermatol Clin 2010;28(4):639-648

- Bhate K, Landeck L, Gonzalez E, et al. Genital contact dermatitis: a retrospective analysis. Dermatitis 2012;21(6):317-320

- Virgil A. Bacileri S, Corazza M. Managing vulvar lichen simplex chronicus. J Reprod Med 2001;46:343-346

- Burrows LJ, Shaw HA, Goldstein AT. The vulvar dermatoses. J Sex Med 2008;5(2):276-283

- Ermertcan AT, Gencoglan G, Temeltas G, et al. Sexual dysfunction in female patients with neurodermatitis. J Androl 2011;32(2):165-169

- Smith YR, Haefner HK. Vulvar lichen sclerosus: pathophysiology and treatment. Am J Dermtol 2004;5:105-125. (Level III)

- Val I, Almeida G. An overview of lichen sclerosus. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2005;48:808-817. (Level III)

- Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin 2010;28(4):707-715

- Van de Nieuwenhof HP, Meeuwis KA, Nieboer TE, et al. The effect of vulvar lichen sclerosus on quality of life and sexual functioning. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2010;31(4):279-284

- Burrows LJ, Creasey A, Goldstein AT. The treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus and female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2011;8(1):219-222

- Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther 2004;17:28-37. (Level III)

- Neill SM, Lewis FM, Tatnall FM, Cox NH. British Association of Dermatologistsí guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus 2010. Br J Dermatol 2010;163(4):672-682

- Goldstein AT, Creasey A, Pfau R, et al. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial of clobetasol versus pimecrolimus in patients with vulvar lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;4(6):e99-104

- Suckling J, Lethaby A, Kennedy R. Local estrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 4. Art. No.:CD001500. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD001500.pub2. (Level III)

- Rioux JE, Devlin C, Gelfand MM, et al. 17beta-estradiol vaginal tablet versus conjugated equine estrogen vaginal cream to relieve menopausal atrophic vaginitis. Menopause 2000;7:156-161. (Level I)

- Nappi RE, Ferdeghini F, Sampaolo P, et al. Clitoral circulation in postmenopausal women with sexual dysfunction: a pilot randomized study with hormone therapy. Maturitas 2006;55:288-295. (Level II-1)

- ACOG Practice Bulletin. Diagnosis and management of vulvar skin disorders. Obstet Gynecol 2008;111:1243-1253

- Cooper SM, Haefner HK, Abrahams-Gessel S, et al. Vulvovaginal lichen planus treatment: a survey of current practices. Arch Dermatol 2008;144(11):1520-1521

- Goldstein AT, Metz A. Vulvar lichen planus. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2005;48(4):818-823

- Lloyd J, Flanagan AM. Mammary and extramammary Pagetís disease. J Clin Pathol 2000;53:742-749. (Level III)

- Lynch PJ, Moyal-Barracco M, Scurry J, Stockdale C. 2011 ISSVD terminology and classification of vulvar dermatological disorders: an approach to clinical diagnosis. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2012:16(4): 339-344

- De Magnis A, Checcucci V, Catalano C, Corazzesi A, et al. Vulvar Paget disease: a large single-centre experience on clinical presentation, surgical treatment, and long-term outcomes. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2013;17(2):104-110

- Achar S, Kundu S. Principles of office anesthesia: part I. Infiltrative anesthesia. Am Fam Physician 2002;66:91Ė94. (Level III)

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol 2013;14(1):27-47

- Tebes S, Cardosi R, Hoffman M. Pagetís disease of the vulva. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;187(2):281-284

- Choi JB, Yoon ES, Yoon DK, et al. Failure of carbon dioxide laser treatment in three patients with penoscrotal extramammary Pagetís disease. BJU Int 2001;88:297-298

- Denehy T, Taylor RR, McWeeney DT, et al. Successful immune modulation therapy with topical imiquimod 5% cream in the management of recurrent extramammary Pagetís disease of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 2006;101(1 Suppl 1):S88-S89

- Ye JN, Rhew DC, Yip F, et al. Extramammary Pagetís disease resistant to surgery and imiquimod monotherapy but responsive to imiquimod combination topical chemotherapy with 5-FU and retinoic acid: a case report. Cutis 2006;77:245-250

- Yanagi T, Kato N, Yamane N, et al. Radiotherapy for extramammary Pagetís disease: histological findings after radiotherapy. Clin Exp Dermatol 2007;32:506-508

Опубликован: 13 August 2015

Dedicated to Women's and Children's Well-being and Health Care Worldwide

www.womenshealthsection.com