Diagnosis of Vaginitis & Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

WHEC Practice Bulletin and Clinical Management Guidelines for healthcare providers. Educational grant provided by Women's Health and Education Center (WHEC).

Vaginal infections represent an enormous, yet often underestimated element of female healthcare. Each year millions of women report symptoms of vaginitis to their clinician. Vaginitis can create a great deal of discomfort, stress, and anxiety in patients; furthermore these conditions may exert untoward and long-term effects on well-being, reproductivity and even mortality. The success with which vaginitis is managed depends largely on the counseling methods used by the healthcare provider. Each infection, and each woman requires a tailored explanation that includes the condition itself, its causes and its consequences. When delivered in a sensitive and comprehensive manner, this information can go a long way toward relieving patient's fears and enabling them to feel in control of their condition. Vaginal infections account for more than 10 million office visits each year. Some forms of vaginitis are initially asymptomatic but subsequently lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

The purpose of this document is to understand three most common vaginal infections: bacterial vaginosis; candida vaginitis (yeast); and trichomonas vaginitis. Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and its management are also discussed to understand its causes and appropriate treatment. Vaginal infections can raise very serious concerns for patients. The manner in which women respond to the information about their infection, and how well they succeed with practices to treat it and prevent recurrences, depends largely on their healthcare provider's counseling methods.

Bacterial Vaginosis (BV)

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is currently the most prevalent form of vaginal infection of reproductive age women in the United States. The average incidence of BV is estimated to be 32%-64% in patients visiting sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic, 12%-25% in other clinic populations and 10%-26% in patients visiting obstetric clinics. The terminology: Bacterial Vaginosis (BV), the currently accepted name for this disease, has evolved over almost 100 years. BV has been formerly known as: nonspecific vaginitis, Haemophilus vaginalis, Gardnerella vaginalis, Corynebacterium vaginalis. BV is believed to represent a synergistic polymicrobial infection characterized by an overgrowth of bacteria normally found in the vagina. Lactobacilli-dominated flora is replaced by mixed, predominantly anaerobic flora. Lactobacilli are absent or greatly reduced in BV patients. Anaerobes: Bacteroides spp, Peptostreptococcus spp, Mobiluncus spp. Facultative Anaerobes: Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis are commonly seen and concentration of anaerobic bacteria increase 100- to 1,000-fold in woman with BV.

Clinical Picture: most common symptom is unpleasant, fishy or musty vaginal odor. Increased vaginal discharge is common and it is usually thin, gray or white and homogenous and it tends to adhere to the vaginal wall. Vaginal itching and irritation may be present. BV has been associated with: pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), endometritis, cervicitis, postoperative infections, mildly abnormal Pap smear (ASCUS) and possible link to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). In pregnant patients possibility of preterm labor, amniotic fluid infection and preterm premature rupture of the membranes (PROM) is seen.

Diagnosis: a clinical diagnosis of BV is defined by three out of four of the following: (1) the presence of homogenous discharge (2) pH>4.5 (3) positive KOH whiff test (4) presence of clue cells on microscopic assessment of a saline smear. KOH Whiff Test: a mix of 10%-20% KOH and vaginal fluid aids in detecting a foul, fishy odor. This strong unpleasant odor is indicative of BV or Trichomonas.

Treatment: Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines

Recommended Rx -- Non-pregnant Women

Metronidazole oral 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days; or metronidazole gel 0.75% one 5 g applicator intravaginally once a day for 5 days; or clindamycin cream 2% one 5 g applicator intravaginally for 7 days.

Alternatives -- metronidazole 2 g orally in a single dose; or clindamycin 300 mg orally twice a day for 7 days; or clindamycin ovules 100 g intravaginally once at bed-time for 3 days.

Pregnancy -- Metronidazole oral 250 mg orally three times a day for 7 days; or clindamycin oral 300 orally twice a day for 7 days

Treating the partner is debatable. Numerous published clinical trials have failed to demonstrate a benefit in treating sexual partners of women with BV. The argument, that BV is a sexually transmitted disease (STD), is widely debated. While BV is found more frequently in sexually active women, BV has also been detected in virginal women. The common recovery of G. vaginalis from male sexual partners also obscures the issue of sexual transmission. However, no relationship was found between BV recurrence and the isolation of G. vaginalis from sexual partner.

Candida Vaginitis (Yeast)

Candidiasis (yeast) is the second most common vaginal infection. True fungal infections account for <33% of all vaginal infections. Yeast infections are not associated with serious health risks. Candida and other organisms may be found in small numbers in the normal vagina as well as in the mouth and digestive tract. Common causes of candida overgrowth include: (1) antibiotics (2) diabetes (3) pregnancy, or (4) human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Yeast infections are caused by one of many types of fungus called Candida albicans - is the most common pathogen; C glabrata and C tropicalis may also be present.

Clinical picture: white "cottage-cheese like" discharge is the most common symptom, usually with no odor and there may be signs of vaginal and vulvar pruritis.

Diagnosis: should be based on presence of hyphae or spores on KOH wet prep. Perform culture only for refractory cases or relapses because up to 20% of women may have positive cultures without disease. Evaluate patients with persistent infection for diabetes and HIV. Vaginal candida infections are usually associated with a pH<4.5.

Treatment: Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guidelines

Recommended Rx -- butoconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally for 3 days; or butoconazole 2% cream 5 g (butoconazole 1-sustained release) single intravaginal application. OR

Clotrimazole 1% cream 5 g intravaginally for 7-14 days; or clotrimazole 100 mg vaginal tablet for 7 days; or clotrimazole 100 mg vaginal tablet 2 tablets for 3 days; or clotrimazole 500 mg vaginal tablet, 1 tablet in a single application. OR

Miconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally for 7 days; or miconazole 100 mg vaginal suppository, one suppository for 7 days; or miconazole 200 mg vaginal suppository, one suppository for 3 days. OR

Nystatin 100,000 U vaginal tablet, 1 tablet for 14 days; or tioconazole 6.5% ointment 5 g intravaginally in a single application; or fluconazole 150 mg oral tablet, one tablet in a single dose. OR

Terconazole 0.4% cream 5 g intravaginally for 7 days; or terconazole 0.8% cream 5 g intravaginally for 3 days; or terconazole 80 mg vaginal suppository, 1 suppository for 3 days.

Treating the partner does not improve the initial response to therapy nor does the frequency of recurrence. Routine treatment of asymptomatic sex partners is not recommended. If candidal colonization of the oral mucosa and ejaculate cultures (not prostatic cultures) is present, it needs to be treated. The therapeutic options include clotrimazole oral touches, one lozenge five times a day for 14 days; nystatin oral pastilles, one pastille five times a day for 10 days; or chlorhexidine gluconate (Peridex) oral rinse 0.5 oz in the morning and bedtime (rinse and expectorate). For ejaculate colonization, therapeutic options include oral fluconazole 100 mg daily for 14 days or itraconazole 100 mg twice a day for 15 days. Topical boric acid has been used for decades as a treatment for candidal infection, and some women may still use it today as an alternative treatment.

Trichomonas Vaginitis (Trichomoniasis):

Trichomonas vaginalis was initially identified by Donne in 1836 and is thought to be the first recognized sexually transmitted pathogen. Trichomoniasis is caused by a single-cell parasite known as a trichomonad. In the United States, Trichomoniasis is particularly prevalent among young, sexually active individuals and it is estimated to affect 5 million US residents of all age groups. It is seen 50%-75% in prostitutes; 5%-15% of women visiting gynecology clinics; 7%-32% of women in STD clinics; 5% of women in family planning clinics. Since the parasite rarely causes symptoms in men, reinfection of women by untreated men is common. Risk factors for acquiring Trichomonas include: (1) multiple sexual partners (2) history of previous STD (3) coexistent infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae or other STDs.

Clinical picture: most common symptoms are internal and external itching and yellow-green frothy vaginal discharge with foul, fishy odor. Dysuria and dyspareunia may be present. Intense erythema of the vaginal mucosa and cervical patechiae ("strawberry cervix") is sometimes seen.

Diagnosis: Wet-mount involves examining slides of vaginal discharge under the microscope. Look for motile trichomonads on saline smear and it 70% sensitive. Culturing for Trichomonas will detect approximately 10%-30% more cases of Trichomonas than a wet mount. Culture should only be used when a wet-mount is inconclusive.

Treatment: Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines:

Recommended Rx -- metronidazole 2 g orally in a single dose.

Alternatives -- metronidazole 500 mg twice a day for 7 days.

Treatment of the sexual partner is necessary.

Differential Diagnosis of Vaginal Infections:

Source: APGO Educational Series in Women's Health Issues

Diagnostic |

Syndrome |

|||

Normal |

Bacterial Vaginosis |

Trichomonas Vaginosis |

Candida Vulvovaginitis |

|

Vaginal pH |

3.8-4.2 |

>4.5 |

>4.5 |

£4.5 (usually) |

Discharge |

White, clear, flocculent |

Thin, homogeneuous, white, greay, adherent, often increased |

Yellow-green, frothy, adherent, increased |

White, curdy, 'cottage cheese-like', sometimes increased |

Amine odor (KOH) |

Absent |

Present (fishy) |

May be present (fishy) |

Absent |

Main patient |

None |

Discharge, bad odor (possibly worse after intercourse), possible itching |

Frothy discharge, bad odor, vulvar pruritius, dysuria |

Itching/burning, discharge |

| Microscopic |

|

|

|

|

Lactobacilli, epithelial cells |

Clue cells with adherent coccoid bacteria, no WBCs |

Trichomonads, |

Budding yeast, |

|

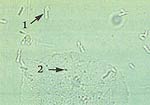

1. Lactobacilli |

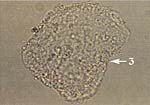

3. Clue Cell |

4. Trichomonad |

6. Budding yeast |

|

Photographs curtsey of D. Ferris, MD

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID)

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is a general term for acute, sub-acute, recurrent, or chronic infection of the oviducts and ovaries, often with involvement of adjacent tissues. Most infections seen in clinical practice are bacterial, but viral, fungal and parasitic infections may occur. The term PID is vague at best and should be discarded in favor of more specific terminology. This should include identification of the affected organs, the stage of the infection and if possible the causative agent. This specificity is especially important in view of the rising incidence of venereal disease and its complications. The following is a general classification of pelvic infections by frequency of occurrence:

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Acute salpingitis: Gonococcal and Non-gonococcal

- IUD-related pelvic cellulitis

- Tubo-ovarian abscess

- Pelvic abscess

- Puerperal infections

- Post-cesarean section

- Post-vaginal delivery

- Post-operative gynecologic surgery

- Cuff cellulitis and parametritis

- Vaginal cuff abscess

- Tubo-ovarian abscess

- Abortion-associated infections

- Post-abortal cellulitis

- Incomplete septic abortion

- Secondary to other infections

- Appendicitis

- Diverticulitis

- Tuberculosis

Essentials of Diagnosis: onset of lower abdominal and pelvic pain associated with vaginal discharge, abdominal, uterine, adnexal and cervical motion tenderness plus one or more of the following helps to make the diagnosis: (a) Temperature above 38oC (100.4oF); (b) Leukocyte count greater than 10,000/ml; (c) Inflammatory mass by examination or sonography; (d) Gram-negative intracellular diplococci in cervical secretions; (e) Purulent material (WBC) from peritoneal cavity (culdocentesis or laparoscopy). In most cases symptoms appear shortly after the onset or cessation of menses. There is often an associated purulent vaginal discharge. Nausea may occur, with or without vomiting abdominal tenderness is often encountered, usually in both lower quadrants. Bimanual examination typically elicits extreme tenderness on movement of the cervix and uterus and palpation of the parametria. Differential diagnosis -- acute salpingitis must be differentiated from acute appendicitis, ectopic pregnancy, ruptured corpus luteum cyst with hemorrhage, deverticulitis, infected septic abortion, torsion of an adnexal mass, degeneration of a leiomyoma, endometriosis, acute urinary tract infection, regional enteritis and ulcerative colitis.

Treatment: Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines

Recommended Rx -- Regimen A (oral therapy): ofloxacin 400 mg orally twice a day for 14 days; OR levofloxacin 500 mg orally once a day for 14 days with or without metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 14 days.

Regimen B:

- ceftriaxone 250 mg IM in a single dose; OR cefoxitin 2 g IM in a single dose and probenecid 1 g orally administered concurrently in a single dose.

- Other parenteral third-generation cephalosporin (eg ceftrizoxime or cefotaxime) plus doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 14 days with or without metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 14 days.

Prognosis: a favorable outcome is directly related to the promptness with which adequate therapy is begun. For example, the incidence of infertility is directly related to the severity of tubal inflammation judged by laparoscopic examination. A single episode of salpingitis has been shown to cause infertility in 12%-18% of women. Tubal occlusion was demonstrated in only about 10% of these patients regardless of whether or not there had been a gonococcal or non-gonococcal infection. Non-gonococcal infections predispose more commonly to ectopic pregnancy, and thus carry a worse prognosis for subsequent viable pregnancy. The ability and willingness of the patient to cooperate with her physician are important to the outcome of patients with the milder cases who are adequately treated on an outpatient basis. Follow-up care and education are necessary to prevent reinfection and complications.

Summary:

Effective counseling can go a long way toward helping patients gain knowledge about vaginal infections, ultimately resulting in reduced stress, greater comfort, and better treatment success. Healthcare providers are encouraged to educate patients about their infections on a one-on-one basis, and remain sensitive to concerns and questions; both spoken and unspoken; that are on women's minds during their visits. Effective management of the three most prevalent forms of vaginitis requires close attention to diagnostic accuracy, as well as infection-specific treatment strategies.

Please note: Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) and Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS) are discussed in separate chapters.

Suggested Reading:

- Faro S: Candida. In Benign Diseases of the Vulva and Vagina. Fifth edition. Edited by RH Kaufman, S Faro, D Brown. Philadelphia, Elsevier/Mosby, 2004, pp 339-335

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006,55:1-94. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5511a1.htm

- Sweet R, Gibbs R (editors): Infectious vulvovaginitis. In Infectious Diseases of the Female Genital Tract. Fourth edition. New York, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002, pp 337-354

- Landers D, Weisenfield H, Heine R, et al. Predictive value of the clinical diagnosis of lower genital tract infection in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:1004-1010

- Denitrezen S, Dirlik O, Beksac M. The association of Candida infection with intrauterine contraceptive device. Cen Eur J Public Health 2005;13:32-34

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins - Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetricians-gynecologists, Number 72, May 2006: Vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1195-1206

- Ness RB, Hillier SL, Kip KE et al. Douching, pelvic inflammatory disease, and incident gonococcal and chlamydial genital infection in a cohort of high-risk women. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:186-195. (Level II-2)

- Hoffstetter SE, Barr S, LeFevre C et al. Self-reported yeast symptoms compared with clinical wet mount analysis and vaginal yeast culture in a specific clinic setting. J Reprod Med 2008;53:402-406

Published: 23 September 2009

Dedicated to Women's and Children's Well-being and Health Care Worldwide

www.womenshealthsection.com